Book:Choosing and Implementing a Cloud-based Service for Your Laboratory/What is cloud computing?/Cloud computing services and deployment models

1.2 Cloud computing services and deployment models

You've probably heard terms like "software as a service" and "public cloud," and you may very well be familiar with their significance already. However, let's briefly run through the terminology associated with cloud services and deployments, as that terminology gets used abundantly, and it's best we're all clear on it from the start. Additionally, the cloud computing paradigm is expanding into areas like "hybrid cloud" and "serverless computing," concepts which may be new to many.

Mentioned earlier was NIST's 2011 definition of cloud computing. When that was published, NIST defined three service models and four deployment models (Table 1)[1]:

| Table 1. The three service models and four deployment models for cloud computing, as defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2011[1] | |

| Service models | |

|---|---|

| Model | Description |

| Software as a Service (SaaS) | "The capability provided to the consumer is to use the provider’s applications running on a cloud infrastructure. The applications are accessible from various client devices through either a thin client interface, such as a web browser (e.g., web-based email), or a program interface. The consumer does not manage or control the underlying cloud infrastructure including network, servers, operating systems, storage, or even individual application capabilities, with the possible exception of limited user-specific application configuration settings." |

| Platform as a Service (PaaS) | "The capability provided to the consumer is to deploy onto the cloud infrastructure consumer-created or acquired applications created using programming languages, libraries, services, and tools supported by the provider. The consumer does not manage or control the underlying cloud infrastructure including network, servers, operating systems, or storage, but has control over the deployed applications and possibly configuration settings for the application-hosting environment." |

| Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) | "The capability provided to the consumer is to provision processing, storage, networks, and other fundamental computing resources where the consumer is able to deploy and run arbitrary software, which can include operating systems and applications. The consumer does not manage or control the underlying cloud infrastructure but has control over operating systems, storage, and deployed applications; and possibly limited control of select networking components (e.g., host firewalls)." |

| Deployment models | |

| Model | Description |

| Private cloud | "The cloud infrastructure is provisioned for exclusive use by a single organization comprising multiple consumers (e.g., business units). It may be owned, managed, and operated by the organization, a third party, or some combination of them, and it may exist on or off premises." |

| Community cloud | "The cloud infrastructure is provisioned for exclusive use by a specific community of consumers from organizations that have shared concerns (e.g., mission, security requirements, policy, and compliance considerations). It may be owned, managed, and operated by one or more of the organizations in the community, a third party, or some combination of them, and it may exist on or off premises." |

| Public cloud | "The cloud infrastructure is provisioned for open use by the general public. It may be owned, managed, and operated by a business, academic, or government organization, or some combination of them. It exists on the premises of the cloud provider." |

| Hybrid cloud | "The cloud infrastructure is a composition of two or more distinct cloud infrastructures (private, community, or public) that remain unique entities, but are bound together by standardized or proprietary technology that enables data and application portability (e.g., cloud bursting for load balancing between clouds)." |

Nearly a decade later, the picture painted in Table 1 is now more nuanced and varied, with slight changes in definitions, as well as additions to the service and deployment models. Cloudflare actually does a splendid job of describing these service and deployment models, so let's paraphrase from them, as seen in Table 2.

| Table 2. A more modern look at service models and deployment models for cloud computing, as inspired largely by Cloudflare | |

| Service models | |

|---|---|

| Model | Description |

| Software as a Service (SaaS) | This service model allows customers, via an internet connection and a web browser or app, to use software provided by and operated upon a cloud provider and its computing infrastructure. The customer isn't worried about anything hardware-related; from their perspective, they just want the software hosted by the cloud provider to be reliably and effectively operational. If the desired software is tied to strong regulatory or security standards, however, the customer must thoroughly vet the vendor, and even then, there is some risk in taking the word of the vendor that the application is properly secure since customers usually won't be able to test the software's security themselves (e.g., via a penetration test).[2] |

| Platform as a Service (PaaS) | This service model allows customers, via an internet connection and a web browser, to use not only the computing infrastructure (e.g., servers, hard drives, networking equipment) of the cloud provider but also development tools, operating systems, database management tools, middleware, etc. required to build web applications. As such, this allows a development team to spread around the world and still productively collaborate using the cloud provider's platform. However, app developers are essentially locked into the vendor's development environment, and additional security challenges may be introduced if the cloud provider has extended its infrastructure to one or more third parties. Finally, PaaS isn't truly "serverless," as applications won't automatically scale unless programmed to do so, and processes must be running most or all the time in order to be immediately available to users.[3] |

| Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) | This service model allows customers to use the computing infrastructure of a cloud provider, via the internet, rather than invest in their own on-premises computing infrastructure. From their internet connection and a web browser, the customer can set up and allocate the resources required (i.e., scalable infrastructure) to build and host web applications, store data, run code, etc. These activities are often facilitated with the help of virtualization and container technologies.[4] |

| Function as a Service (FaaS) | This service model allows customers to run isolated or modular bits of code, preferably on local or "edge" cloud servers (more on that later), when triggered by an element, such as an internet-connected device taking a reading or a user selecting an option in a web application. The customer has the luxury of focusing on writing and fine-tuning the code, and the cloud provider is the one responsible for allocating the necessary server and backend resources to ensure the code is run rapidly and effectively. As such, the customer doesn't have to think about servers at all, making FaaS a "serverless" computing model.[5] |

| Backend as a Service (BaaS) | This service model allows customers to focus on front-end application services like client-side logic and user interface (UI), while the cloud provider provides the backend services for user authentication, database management, data storage, etc. The customer uses APIs and software development kits (SDKs) provided by the cloud provider to integrate customer frontend application code with the vendor's backend functionality. As such, the customer doesn't have to think about servers, virtual machines, etc. However, in most cases, BaaS isn't truly serverless like FaaS, as actions aren't usually triggered by an element but rather run continuously (not as scalable as serverless). Additionally, BaaS isn't generally set up to run on the network's edge.[6] |

| Deployment models | |

| Model | Description |

| Private cloud | This deployment model involves the provision of cloud computing infrastructure and services exclusively to one customer. Those infrastructure and service offerings may be hosted locally on-site or be remotely and privately managed and accessed via the internet and a web browser. Those organizations with high security and regulatory requirements may benefit from a private cloud, as they have direct control over how those policies are implemented on the infrastructure and services (i.e., don't have to consider the needs of other users sharing the cloud, as in public cloud). However, private cloud may come with higher costs.[7] |

| Community cloud | This deployment model, while not discussed often, still has some relevancy today. This model falls somewhere between private and public cloud, allowing authorized customers who need to work jointly on projects and applications, or require specific computing resources, in an integrated manner. The authorized customers typically have shared interests, policies, and security/regulatory requirements. Like private cloud, the computing infrastructure and services may be hosted locally at one of the customer's locations or be remotely and privately managed, with each customer accessing the community cloud via the internet. Given a set of common interest, policies, and requirements, the community cloud benefits all customers using the community cloud, as does the flexibility, scalability, and availability of cloud computing in general. However, with more users comes more security risk, and more detailed role-based or group-based security levels and enforcement may be required. Additionally, there must be solid communication and agreement among all members of the community to ensure the community cloud operates as efficiently and securely as possible.[8] |

| Public cloud | This deployment model is what typically comes to mind when "cloud computing" is discussed, involving a cloud provider that provides computing resources to multiple customers at the same time, though each individual customer's applications, data, and resources remain "hidden" from all other customers not authorized to view and access them. Those provided resources come in many different services model, with SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS being the most common. Traditionally, the public cloud has been touted as being a cost-effective, less complex, relatively secure means of handling computing resources and applications. However, for organizations tied to strong regulatory or security standards, the organizaiton must thoroughly vet the cloud vendor and its approach to security and compliance, as the provider may not be able to meet regulatory needs. There's also the concern of vendor lock-in or even loss of data if the customer becomes too dependent on that one vendor's services.[9] |

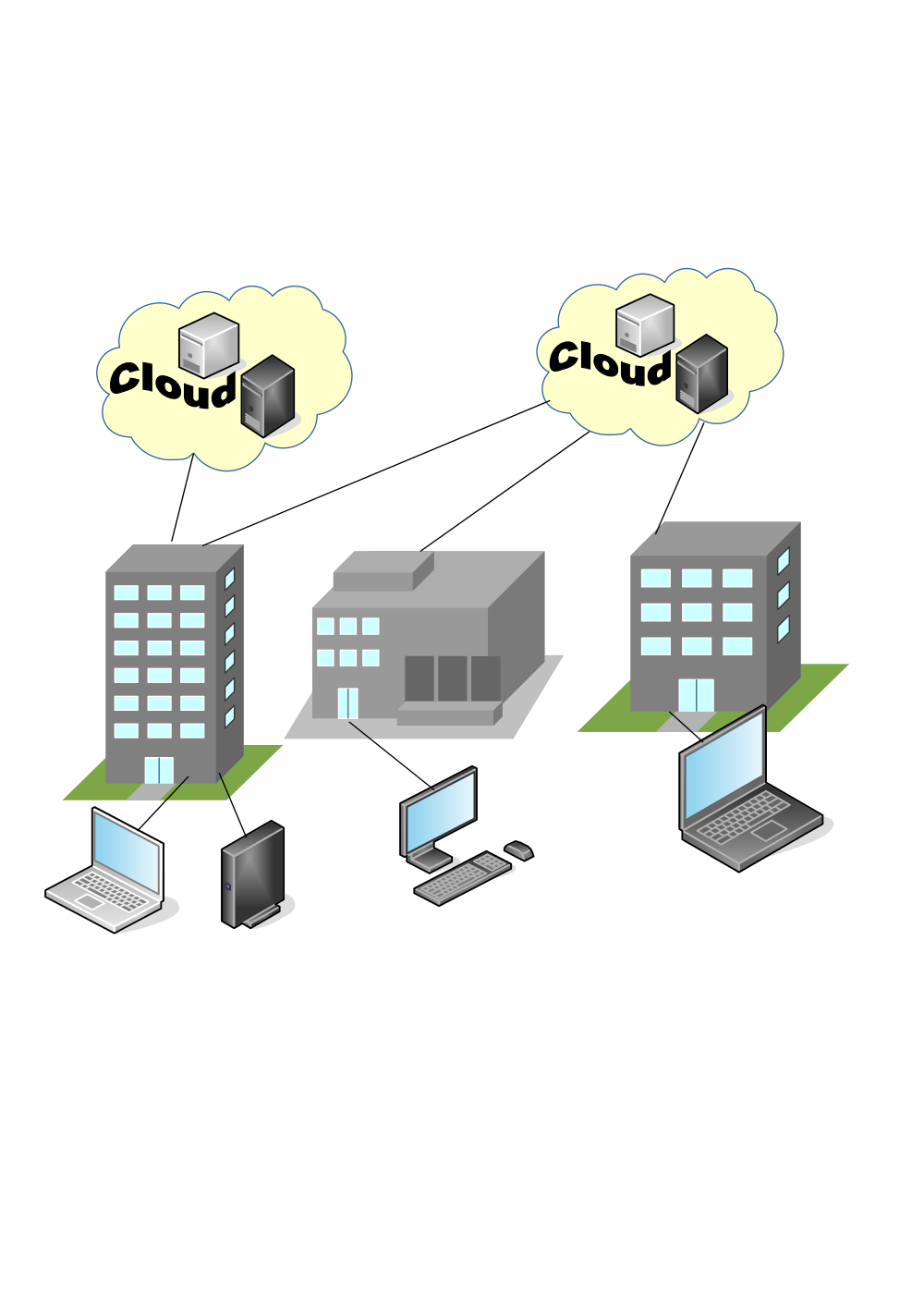

| Hybrid cloud | This deployment model takes both private cloud and public cloud models and tightly integrates them, along with potentially any existing on-premises computing infrastructure. (Figure 2) The optimal end result is one seamless operating computing infrastructure, e.g., where a private cloud and on-premises infrastructure houses critical operations and a public cloud is used for data and information backup or computing resource scaling. Advantages include great flexibility in deployments, improved backup options, resource scalability, and potential cost savings. Downsides include greater effort required to integrate complex systems and make them sufficiently secure. Note that hybrid cloud is different from multicloud in that it combines both public and private computing components.[10] |

| Multicloud | This deployment model takes the concept of public cloud and multiplies it. Instead of the customer relying on a singular public cloud provider, they spread their cloud hosting, data storage, and application stack usage across more than one provider. The advantage to the customer is redundancy protection for data and systems and better value by tapping into different services. Downside comes with increased complexity in managing a multicloud deployment, as well as the potential for increased network latency and a greater cyber-attack surface. Note that multicloud requires multiple public clouds, though a private cloud can also be in the mix.[11] |

| Distributed cloud | This up-and-coming deployment model takes public cloud and expands it, such that a provider's public cloud infrastructure can be located in multiple places but be leveraged by a customer wherever they are, from a single control structure. As IBM puts it: "In effect, distributed cloud extends the provider's centralized cloud with geographically distributed micro-cloud satellites. The cloud provider retains central control over the operations, updates, governance, security, and reliability of all distributed infrastructure."[12] Meanwhile, the customer can still access all infrastructure and services as an integrated cloud from a single control structure. The benefit of this model is that, unlike multicloud, latency issues can largely be eliminated, and the risk of failures in infrastructure and services can be further mitigated. Customers in regulated environments may also see benefits as data required to be in a specific geographic location can be better guaranteed with the distributed cloud. However, some challenges to this distributed model involve the allocation of public cloud resources to distributed use and determining who's responsible for bandwidth use.[13] |

While Table 2 addresses the basic ideas inherent to these service and deployment models, even providing some upside and downside notes, we still need to make further comparisons in order to highlight some fundamental differences in otherwise seemingly similar models. Let's first compare PaaS with serverless computing or FaaS. Then we'll examine the differences among hybrid, multi-, and distributed cloud models.

1.2.1 Platform-as-a-service vs. serverless computing

As a service model, platform as a service or PaaS uses both the infrastructure layer and the platform layer of cloud computing. Hosted on the infrastructure are platform components like development tools, operating systems, database management tools, middleware, and more, which are useful for application design, development, testing, and deployment, as well as web service integration, database integration, state management, application versioning, and application instrumentation.[14][15][16] In that regard, the user of the PaaS need not think about the backend processes.

Similarly, serverless computing or FaaS largely abstracts away (think "out of sight, out of mind") the servers running any software or code the user chooses to run on the cloud provider's infrastructure. The user practically doesn't need to know anything about the underlying hardware and operating system, or how that hardware and software handles the computational load of running your software or code, as the cloud provider ends up completely responsible for that. However, this is where the similarities stop.

Let's use Amazon's AWS Lambda serverless computing service as an example for comparison with PaaS. Imagine you have some code you want performed on your website when an internet of things (IoT) device in the field takes a reading for your environmental laboratory. From your AWS Lambda account, you can "stage and invoke" the code you've written (it can be in any programming language) "from within one of the support languages in the AWS Lambda runtime environment."[17][18] In turn, that runtime environment runs on top of Amazon Linux 2, an Amazon-developed version of Red Hat Enterprise running as a Linux server operating system.[19] This can then be packaged into a container image that runs on Amazon's servers.[18] When a designated event occurs (in this example, the internet-connected device taking a reading), a message is communicated—typically via an API—to the serverless code, which is then triggered, and Amazon Lambda provisions only the necessary resources to see the code to completion. Then the AWS server spins down those resources afterwards.[20] Yes, there are servers still involved, but the critical point is the customer need only to properly package their code up, without any concern whatsoever of how the AWS server manages its use and performance. In that regard, the code is said to be run in a "serverless" fashion, not because the servers aren't involved but because the code developer is effectively abstracted from the servers running and managing the code; the developer is left to only worry about the code itself.[20][21]

PaaS is not serverless, however. First, a truly serverless model is significantly different in its scalability. The serverless model is meant to instantly provide computing resources based upon a "trigger" or programmed element, and then wind down those resources. This is perfect for the environmental lab wanting to upload remote sensor data to the cloud after each collection time; only the resources required for performing the action to completion are required, minimizing cost. However, this doesn't work well for a PaaS solution, which doesn't scale up automatically unless specifically programmed to. Sure, the developer using PaaS has more control over the development environment, but resources must be scaled up manually and left continuously running, making it less agile than serverless. This makes PaaS more suitable for more prescriptive and deliberate application development, though its usage-based pricing is a bit less precise than serverless. Additionally, serverless models aren't typically offered with development tools, as usually is the case with PaaS, so the serverless code developer must turn to their own development tools.[3][22]

1.2.2 Hybrid cloud vs. multicloud vs. distributed cloud

At casual glance, one might be led to believe these three deployment models aren't all that different. However, there are some core differences to point out, which may affect an organization's deployment strategy significantly. As Table 2 notes:

- Hybrid cloud takes private cloud and public cloud models (as well as an organization's local infrastructure) and tightly integrates them. This indicates a wide mix of computing services is being used in an integrated fashion to create value.[10][23]

- Multicloud takes the concept of public cloud and multiplies it. This indicates that two or more public clouds are being used, without a private cloud to muddy the integration.[11]

- Distributed cloud takes public cloud and expands it to multiple localized or "edge" locations. This indicates that a public cloud service's resources are strategically dispersed in locations as required by the user, while remaining accessible from and complementary to the user's private cloud or on-premises data center.[13][24]

As such, an organization's existing infrastructure and business demands, combined with its aspirations for moving into the cloud, will dictate their deployment model. But there are also advantages and disadvantages to each which may further dictate an organization's deployment decision. First, all three models provide some level of redundancy. If a failure occurs in one computing core (be it public, private, or local), another core can ideally provide backup services to fill the gap. However, each model does this in a slightly different way. In a similar way, if additional compute resources are required due to a spike in demand, each model can ramp up resources to smooth the demand spike. Hybrid and distributed clouds also have the benefit of making any future transition to a purely public cloud (be it singular or multi-) easier as part of an organization's processes and data are already found in public cloud.

Beyond these benefits, things diverge a bit. While hybrid clouds provide flexibility to maintain sensitive data in a private cloud or on-site, where security can be more tightly controlled, private clouds are resource-intensive to maintain. Additionally, due to the complexity of integrating that private cloud with all other resources, the hybrid cloud reveals a greater attack surface, complicates security protocols, and raises integration costs.[10] Multicloud has the benefit of reducing vendor lock-in (discussed later in this guide) by implementing resource utilization and storage across more than one public cloud provider. Should a need to migrate away from one vendor arrive, it's easier to continue critical services with the other public cloud vendor. This also lends to "shopping around" for public cloud services as costs lower and offerings change. However, this multicloud approach brings with it its own integration challenges, including differences in technologies between vendors, latency complexities between the services, increased points of attack with more integrations, and load balancing issues between the services.[11] A distributed cloud model removes some of that latency and makes it easier to manage integrations and reduce network failure risks from one control center. It also benefits organizations requiring localized data storage due to regulations. However, with multiple servers being involved, it makes it a bit more difficult to troubleshoot integration and network issues across hardware and software. Additionally, implementation costs are likely to be higher, and security for replicated data across multiple locations becomes more complex and risky.[13][25]

1.2.3 Edge computing?

The concept of "edge" has been mentioned a few times in this chapter, but the topic of clouds, edges, cloud computing, and edge computing should be briefly addressed further, particularly as edges and edge computing gain traction in some industries.[26] Edges and edge computing share a few similarities to clouds and cloud computing, but they are largely different. These concepts can be broken down as such[26][27][28]:

- Clouds: "places where data can be stored or applications can run. They are software-defined environments created by datacenters or server farms." These involve strategic locations where network connectivity is essentially reliable.

- Edges: "also places where data is collected. They are physical environments made up of hardware outside a datacenter." These are often remote locations where network connectivity is limited at best.

- Cloud computing: an "act of running workloads in a cloud."

- Edge computing: an "act of running workloads on edge devices."

In this case, the locations are differentiated from the actions, though it's notable that actions involving the two aren't exclusive. For example, if remote sensors collect data at the edge of a network and, rather than processing it locally at the edge, transfer it to the cloud for processing, edge computing hasn't happened; it only happens if data is collected and processed all at the edge.[27] Additionally, those remote sensors—which are representative of internet of things (IoT) technology—shouldn't be assumed as connected to both a cloud and edge; they all can be connected as part of a network, but they don't have to be. Linux company Red Hat adds[27]:

Clouds can exist without the Internet of Things (IoT) or edge devices. IoT and edge can exist without clouds. IoT can exist without edge devices or edge computing. IoT devices may connect to an edge or a cloud. Some edge devices connect to a cloud or private datacenter, others edge devices only connect to similarly central locations intermittently, and others never connect to anything—at all.

However, edge computing associated with laboratory-tangential industry activities such as environmental monitoring, manufacturing, and mining will most often have IoT devices that don't necessarily rely on a central location or cloud. These industry activities rely on edges and edge computing because 1. those data-based activities must be executed as near to "immediately" as possible, and 2. those data-based activities usually involve large volumes of data, which are impractical to send to the cloud.[26][27][28]

That said, is your laboratory seeking cloud computing services or edge computing services? The most likely answer is cloud computing, particularly if you're seeking a cloud-based software solution to help manage your laboratory activities. However, there may be a few cases where edge computing makes sense for your laboratory, particularly if its a field laboratory in a more remote location. For example, the U.S. Department of Energy's Urban Integrated Field Laboratory is helping U.S. cities like Chicago using localized instrument clusters to gather climate data for local processing.[29] Another example can be found in a biological manufacturing laboratory with a strong need to integrate high-data-output devices to process and act upon that data locally.[30] Finally, consider the laboratory with significant need for environmental monitoring for mission-critical samples; such a laboratory may also benefit from an IoT + edge computing pairing that provides local redundancy in that monitoring program, especially during power and internet disruptions.[31] Just remember that these examples, however, don't represent a majority of lab's needs, which will largely depend more upon clouds and cloud computing to accomplish their goals more effectively.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mell, P.; Grance, T. (September 2011). "The NIST Definition of Cloud Computing" (PDF). NIST. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication800-145.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What Is SaaS? SaaS Definition". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cloud/what-is-saas/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "What is Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS)?". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/serverless/glossary/platform-as-a-service-paas/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What Is IaaS (Infrastructure-as-a-Service)?". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cloud/what-is-iaas/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What is Function-as-a-Service (FaaS)?". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/serverless/glossary/function-as-a-service-faas/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What is BaaS? Backend-as-a-Service vs. serverless". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/serverless/glossary/backend-as-a-service-baas/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What Is a Private Cloud? Private Cloud vs. Public Cloud". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cloud/what-is-a-private-cloud/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ Tucakov, D. (18 June 2020). "What is Community Cloud? Benefits & Examples with Use Cases". phoenixNAP Blog. phoenixNAP. https://phoenixnap.com/blog/community-cloud. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What Is Hybrid Cloud? Hybrid Cloud Definition". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cloud/what-is-a-public-cloud/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "What Is Hybrid Cloud? Hybrid Cloud Definition". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cloud/what-is-hybrid-cloud/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "What Is Multicloud? Multicloud Definition". Cloudflare, Inc. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/cloud/what-is-multicloud/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ IBM Cloud Education (3 November 2020). "Distributed cloud". IBM. https://www.ibm.com/topics/distributed-cloud. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Costello, K. (12 August 2020). "The CIO’s Guide to Distributed Cloud". Smarter With Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/the-cios-guide-to-distributed-cloud. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ Boniface, M.; Nasser, B.; Papay, J. et al. (2010). "Platform-as-a-Service Architecture for Real-Time Quality of Service Management in Clouds". Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Internet and Web Applications and Services: 155–60. doi:10.1109/ICIW.2010.91.

- ↑ Xiong, H.; Fowley, F.; Pahl, C. et al. (2014). "Scalable Architectures for Platform-as-a-Service Clouds: Performance and Cost Analysis". Proceedings of the 2014 European Conference on Software Architecture: 226–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-09970-5_21.

- ↑ Carey, S. (22 July 2022). "What is PaaS (platform-as-a-service)? A simpler way to build software applications". InfoWorld. https://www.infoworld.com/article/3223434/what-is-paas-platform-as-a-service-a-simpler-way-to-build-software-applications.html. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "Serverless Architectures with AWS Lambda: Overview and Best Practices" (PDF). Amazon Web Services. November 2017. https://d1.awsstatic.com/whitepapers/serverless-architectures-with-aws-lambda.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Lambda runtimes". Amazon Web Services. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/lambda/latest/dg/lambda-runtimes.html. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ Morelo, D. (2020). "What is Amazon Linux 2?". LinuxHint. https://linuxhint.com/what_is_amazon_linux_2/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Serverless computing: A cheat sheet". TechRepublic. 25 December 2020. https://www.techrepublic.com/article/serverless-computing-the-smart-persons-guide/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ Fruhlinger, J. (15 July 2019). "What is serverless? Serverless computing explained". InfoWorld. https://www.infoworld.com/article/3406501/what-is-serverless-serverless-computing-explained.html. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ Sander, J. (1 May 2019). "Serverless computing vs platform-as-a-service: Which is right for your business?". ZDNet. https://www.zdnet.com/article/serverless-computing-vs-platform-as-a-service-which-is-right-for-your-business/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ Hurwitz, J.S.; Kaufman, M.; Halper, F. et al. (2021). "What is Hybrid Cloud Computing?". Dummies.com. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://www.dummies.com/article/technology/information-technology/networking/cloud-computing/what-is-hybrid-cloud-computing-174473/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What is Distributed Cloud Computing?". Edge Academy. StackPath. 2021. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210228040550/https://www.stackpath.com/edge-academy/distributed-cloud-computing/. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ "What is Distributed Cloud". Entradasoft. 2020. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20200916021206/http://entradasoft.com/blogs/what-is-distributed-cloud. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Arora, S. (8 August 2023). "Edge Computing Vs. Cloud Computing: Key Differences to Know". Simplilearn. https://www.simplilearn.com/edge-computing-vs-cloud-computing-article. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 "Cloud vs. edge". Red Hat, Inc. 14 November 2022. https://www.redhat.com/en/topics/cloud-computing/cloud-vs-edge. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Bigelow, S.J. (December 2021). "What is edge computing? Everything you need to know". TechTarget Data Center. Archived from the original on 08 June 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20230608045737/https://www.techtarget.com/searchdatacenter/definition/edge-computing. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Chicago State University to serve as ‘scientific supersite’ to study climate change impact". Argonne National Laboratory. 18 July 2023. https://www.anl.gov/article/chicago-state-university-to-serve-as-scientific-supersite-to-study-climate-change-impact. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Laboratory Automation". Edgenesis, Inc. 2023. https://edgenesis.com/solutions/moreDetail/LaboratoryAutomation. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ↑ "Industrial IoT, Edge Computing and Data Streams: A Comprehensive Guide". Flowfinity Blog. 2 August 2023. https://www.flowfinity.com/blog/industrial-iot-guide.aspx. Retrieved 16 August 2023.