Journal:A critical literature review of historic scientific analog data: Uses, successes, and challenges

| Full article title | A critical literature review of historic scientific analog data: Uses, successes, and challenges |

|---|---|

| Journal | Data Science Journal |

| Author(s) | Kelly, Julia A.; Farrell, Shannon L.; Hendrickson, Lois G.; Luby, James; Mastel, Kristen L. |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Minnesota |

| Primary contact | Email: jkelly at umn dot edu |

| Year published | 2022 |

| Volume and issue | 21 |

| Article # | 14 |

| DOI | 10.5334/dsj-2022-014 |

| ISSN | 1683-1470 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://datascience.codata.org/articles/10.5334/dsj-2022-014 |

| Download | https://storage.googleapis.com/jnl-up-j-dsj-files/journals/1/articles/1444/submission/proof/1444-1-10637-1-10-20220728.pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

For years, scientists in fields from climate change to biodiversity to hydrology have used older data to address contemporary issues. Since the 1960s, researchers, recognizing the value of this data, have expressed concern about its management and potential for loss. No widespread solutions have emerged to address the myriad issues around its storage, access, and findability. This paper summarizes observations and concerns of researchers in various disciplines who have articulated problems associated with analog data and highlights examples of projects that have used historical data. The authors also examined selected papers to discover how researchers located historical data and how they used it. While many researchers are not producing huge amounts of analog data today, there are still large volumes of it that are at risk. To address this concern, the authors recommend the development of best practices for managing historic data. This will take communication across disciplines and the involvement of researchers, departments, institutions, and associations in the process.

Keywords: analog data, historic data, data policies, risk of loss, data rescue, dark data

Introduction

Concerns about the management of data—including its preservation, findability, and reuse—are almost entirely focused on recently-generated data in electronic, machine-readable formats. While many of the principles of the management of electronic data such as proper description and good organization apply to data in any format, the discussions about applying those principles to older data in non-electronic formats have not received much attention.

In this paper we review publications in various scientific fields that discuss older data that is in analog or print format and the use or reuse of older data in general. By analog data we mean items in print format such as numeric data as well as field or lab notebooks, photographs, drawings, and maps. Analog data may also be called historic data, legacy data, heritage data, or dark data, although these and other phrases can include older data that is not necessarily in print format. Some authors also use the term "data rescue," which has also been used to describe recent efforts to duplicate and secure electronic data that may be at risk of loss (e.g., the Data Refuge community[1]).

Our interest in this topic began when a few senior faculty members approached the University library for assistance in organizing and possibly housing their analog data.[2] A survey of life sciences researchers on campus revealed that many held analog data and considered it valuable but were unsure of how to preserve it.[3] Nearly all were willing to share it. Given that most researchers now either collect data digitally or quickly transfer any analog data, this is a finite problem; however, because many of the stewards of analog data are nearing retirement, it is timely. We undertook this literature review to learn how scientific researchers are dealing with the analog data in their possession and if any large scale efforts have been undertaken to address the issues.

Types of analog data

Much of the analog data that exists in offices, labs, homes, archives, and other locations is numeric in nature. It was probably collected before electronic spreadsheets were commonly available for both capturing and analyzing data. The format could be loose notebook paper, index cards, large data sheets, or bound or unbound notebooks. It could also take the form of a log, possibly combining numeric and descriptive data in chronological order.

The data may also be descriptive in nature and contained in field notebooks or diaries. The tags associated with museum and herbarium specimens are often mined for the data that they note such as species, location, dates, and other parameters. Although they are inextricably tied, when we discuss analog data we are not including the specimens themselves but just the information on the tags.

Drawings and photographs may accompany other forms of data or may stand on their own, hopefully with enough description to make them useful to current researchers. The same is true of maps, which may be printed or hand drawn.

History of concern about analog data

A number of authors have written about analog data over the last 50+ years, often noting its potential value and lamenting the lack of procedures, funding, and best practices to help support its ongoing use and preservation. Psychologists in the 1960s and 1970s noted not only the importance of new observations coming from the re-examination of older data but also the practice of comparing newly gathered data to historic data.[4][5] Speaking about data that authors have not retained, Wolins suggests a role for professional associations: "If it were clearly set forth by the [American Psychological Association] ... the responsibility for retaining raw data ... this dilemma would not exist."[6] For a time the U.S. government played a role through the American Documentation Institute at the Library of Congress, which accepted some raw data to be preserved.[5] Recently, Buma made use of photographs in Glacier Bay to longitudinally track plant growth and establishment and noted that if it was easier to learn of the existence of older data and to obtain copies, its value would grow.[7][8]

In most cases, authors limit their discussions to the situation in their own subspecialty, although a few have taken a broader view. A notable example is the final report of the Ecological Society of America (ESA) committee on the Future of Long-term Ecological Data.[9] The lengthy report details the situation and offers numerous recommendations for the future. Although it does not exclusively focus on analog data, it states "[a]mong the least secure are data in the hands of an individual researcher who has made little or no provision for long-term curation."[9]

Also in 1995, the National Research Council published both Finding the Forest in the Trees: The Challenge of Combining Diverse Environmental Data and Preserving Scientific Data on Our Physical Universe.[10][11] The first report highlights the variables, measures, and data management, and puts forward 18 recommendations. These call on professional societies, research institutions, funding agencies, and individual researchers to collaborate, carefully plan, focus on interoperability, create rich metadata, and make data more widely available.[10] The latter report notes many problems and few solutions, stating "[t]he most important deficiencies are in the documentation, access, and long-term preservation of data in usable form."[11] Again, analog data was not the focus of these works, but it was covered.

Easterday et al. note the "potential of historical dark data to contribute to the modern digital ecological data landscape."[12] They note the importance of metadata and the need to promote the data and the best practices around it. In his book Repurposing Legacy Data, Berman states that "data repurposing creates value where none was expected."[13] It includes case studies from a variety of disciplines and has chapters on identifying data that might lend itself to repurposing and understanding the organization of older data.[13]

Griffin advocates for the value of "heritage data," noting that much of it is at risk and in order to secure it for future use, "certain priorities need to be re-ordered, new skills acquired and taught, resources redirected, and new networks constructed."[14] Griffin was active in the CODATA Data at Risk Task Group which, along with its successor, the Research Data Alliance’s Data Rescue Interest Group, worked to highlight the value of older data and promote projects that used or preserved it.[15] Patil and Siegel note that bringing more dark data to the forefront will require different incentives from all those involved: "journals, citation indexes, funding agencies, academic institutions and, not least, the researchers themselves."[16] Although they write from a health sciences perspective, this probably applies more broadly.

A number of authors have drawn attention to the use or potential use of analog data in their particular fields. In fisheries, Singer et al.[17] surveyed fellow researchers to get a better idea of how and why they used fish collections in order to inform both researchers and those who manage the collections. The value and possible reuse of data collected at biological field stations has been noted since at least the 1980s.[18] Bowser emphasized the importance of data management and suggested that field station data might be deposited with libraries, historical societies or federal agencies.[18] Easterday et al.[12] make their observations about the use of data science principles by highlighting work from three California field stations, and Michener et al.[19] wrote an article entitled "Biological Field Stations: Research Legacies and Sites for Serendipity."

Ecological researchers have long mined analog data and historical records in their work, according to Beans.[20] While she focuses on journal entries, maps, and photos, she highlights common challenges such as locating material and working with someone else’s organizational scheme. She highlights Loren McClenachan[21][22][23], a marine ecologist who utilizes historical data in her research and also published a policy-oriented article on the benefits of using older data to set baselines in marine studies. Over 20 years ago, Olson and McCord[24][25] wrote two book chapters on data archiving in the ecological sciences. Although the emphasis is on digital data, they spell out recommendations on incentives, metadata, and components of an archive that apply to analog and digital materials.

Kwok[26] reports on the use of older data in the fields of both ecology and climate science. In the area of climate science, Brönnimann et al. are mainly concerned with digital data but provide an overview of efforts to locate and digitize analog data, commenting that "the fraction of yet-to-be-digitized data is difficult to quantify," implying that it is large indeed.[27]

Geological researchers sometimes have an added reason to want to discover and use older data: it may have been collected using methods that are now difficult or impossible to employ due to stricter regulations. Diviacco et al.[28] writes about a project where data was both analog and digital and had been obtained using dynamite. Vearncombe et al.[29][30], using examples from the mining industry, note that "upcycling" of data can mean cost savings as well as new insights from reexamination of data.

A number of disciplines have employed citizen science projects to assist in the analog data efforts. These take the form of both mining older citizen science projects for their data or initiating new projects that provide person-hours to reformat or otherwise transform or collate analog data. Clavero et al.[31][32] examine species lists to study trout decline, Hof and Bright[33] look at previous counts of hedgehogs, and Snäll et al.[34] consider the use of presence data from bird monitoring. A recent citizen science project on the Zooniverse platform involves identifying data in papers written by students at the University of Michigan Field Station.[35]

While many authors bemoan the unfortunate state of older data in their subdisciplines, a few areas offer success stories. Researchers working in biodiversity—many of whom are connected with museums or herbaria which hold physical specimens and their metadata-rich identification tags—are an example. They have built networks and secured funding for several international biodiversity-related projects that address data tied to specimens as well as the objects themselves. Projects include Integrated Digitized Biocollections (iDigBio), Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), and Distributed System of Scientific Collections (DiSSCo). The progress in digitization and dissemination of biodiversity data over the last 20 years is summarized by Nelson and Ellis.[36]

Climate researchers have also made great strides in gathering disparate data in analog and digital format and making it accessible to the global community of scientists. The EU-based Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) and International Data Rescue Portal (I-DARE) serve as examples.

Some contemporary groups that rescue and reuse older analog data have very narrowly focused subject areas. The Living Data Project, sponsored by the Canadian Institute of Ecology and Evolution, funds new projects each year with topics such as "Species ranges, diversity and life history of Neotropical birds" and "Responses of freshwater zooplankton to road salt pollution: A global perspective." Another project, based at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Library (Data Rescue Case Study: Long-Term Livestock Production Data), gathered older data from throughout the US, converted it to electronic formats, and deposited it in AgData Commons.[37]

Field and lab notebooks have been the focus of a number of digitization projects. They may be held in archives, museums, libraries, or research facilities, as well as by individuals. The Biodiversity Heritage Library, in conjunction with several other institutions including the Smithsonian, includes nearly 3,000 scanned field books.[38] On a smaller scale, Texas A&M Libraries has digitized the field notebooks and specimen catalogs of W. B. Davis (1930–1981) and they have been viewed over 1,000 times.[39] Thomer et al.[40] propose a method for efficiently extracting species data from handwritten field notebooks.

Ways that older analog data is utilized

Researchers may use older data in a variety of ways. Some strive to repeat an earlier survey or experiment as closely as possible.[41][42][43][44] Others reexamine older data or incorporate portions of it into their current work.[45][46][47][48] Authors may also have consulted earlier data as they developed their research plans. Mandates for the preservation of data that have emerged in the last 15 years have elevated the topic of data reuse, although most recent research has considered only digital data.[49][50][51]

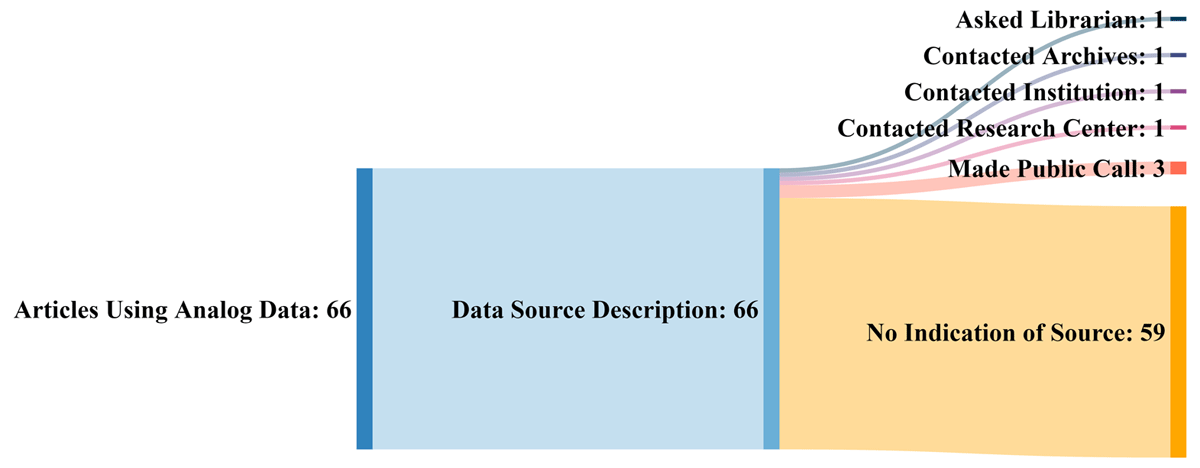

The methods that researchers use to obtain older data often remain a mystery. Large data collections such as iDigBio provide background, training, examples, and other resources for potential data users and authors are likely to mention or cite these collections. This is often not true for projects that use older data. In a preliminary investigation, we conducted examinations of 66 scientific papers that used analog data, and only seven spelled out how the authors located it (see Figure 1). None of the authors of this set of papers mention going back to the original authors of the publications to obtain more detailed information, although it is hard to imagine that none of them took that step.

|

Obtaining data directly from the researchers is known to be problematic, and a statement such as "data available on request" in an article does not always lead to success. A 2014 study focused on 500+ articles from two to 22 years old, and the authors stated, "o]ur results reinforce the notion that, in the long term, research data cannot be reliably preserved by individual researchers."[52] A new study suggests that all data associated with open data publishing needs to go into an open repository before publication. Of authors who indicated that data were available on request in publications, 1,670 (93%) did not respond to a request for data or chose not to share.[53]

In addition to individual researchers, various types of organizations may be in possession of analog data. Government agencies hold weather data as well as the aforementioned museum and herbarium records. Fisheries and agricultural records have also been used, along with conservation-related documents.[54][55][56][57][58] Nonprofits may also hold data from citizen science projects.[33]

Archives can be a source for analog data; this is sometimes where researchers discover field books and diaries.[59][60] They may also hold photographs used by those conducting repeat photography work.[61][62][63] Finally, there are numerous examples of authors reusing analog data that they located using less conventional sources. This includes literature, ship logs, tax records, newspapers, and church records.[64][65][66][67][68][69][70]

Challenges with reusing older data

Scientists note the challenges and potential pitfalls when combining or comparing old and new data. For example, there are few standards or best practices towards these efforts.[9][13][40] In another example, while individual authors provide rich insights from their experiences, finding general guidance for analog data is mostly lacking, unlike the situation with digital data.[18][71] Also unlike the digital data landscape, ownership and stewardship responsibilities are often unclear. Costs for reformatting and preservation of analog data can be high with few options for funding.[9][15] Another concern is that, broadly speaking, institutions have few incentives to save data.[72]

Although not much is known about how individual researchers find the analog data that they reuse, several authors note the difficulty in locating it. It languishes in labs, gets redistributed to multiple locations, or simply disappears.[12][73][74][75][76] Many data repositories, especially those housed at academic institutions, require data to be in machine-readable formats. Some such as Ag Data Commons will accept scanned data. Zenodo, the European Community repository that includes data as well as software and documents, welcomes data in any format, although they are currently working on guidelines for deposit. However, data registries, where metadata about analog data could reside, have not materialized as predicted.[77]

There are also numerous challenges as researchers bring together data gathered years apart. First, combining old and new data sets can be complex.[11][78][79] Metadata is also a concern, as the original description may lack elements and they may have been defined differently in the earlier work.[18][80][81][82][71][83]

Finally, interpreting historic data may involve assumptions and comparison methods that need to be selected carefully.[84][85][86][87][88] Engelhard et al., studying the distribution of North Sea cod, emphasized "the well-known problems with fisheries data such as discarding and misreporting practices by fishers."[89] Beans[20] notes that this underreporting was often due to attempts to minimize taxes on a boat’s catch. Historical records may also have biases that must be dealt with when comparing with current surveys.[58][90][91][92]

Possible paths forward

While the individuals who are the current stewards of analog data and the organizations where they work have major parts to play in the solution to this issue, other entities can also take a role in developing solutions. Although few professional societies are in a position to host a data repository, there are other important roles that they can play. They could investigate and report on the status of analog data availability, use, and status in their realm, like the ESA. If they publish journals, they could encourage authors to cite data papers and accept data papers where appropriate. Societies could call on their members to describe and preserve their own analog data. They could also endorse standards for metadata. If they have the financial means, they could fund the digitization of selected data.

Funding agencies already play a large role in the preservation and reuse of recently-produced electronic data through their mandates, and they could also play a role with older data. Agencies could encourage pre-mandate grant recipients to make their data available or follow the lead of the USDA, which welcomes scanned as well as machine-readable data from pre-mandate grant recipients in its Ag Data Commons repository. Agencies could promote the idea of data papers for material from earlier grants and endorse particular repositories in their subject areas. Funders could also award grants to projects that preserve analog data or make it more easily findable.

What can individual researchers do? They can organize, inventory, and describe any analog data in their purview and document details about how it was generated.[93] Many standards exist for doing this with digital data, and those standards can be used for analog data as well. In a survey of those holding analog data, many reported that there was a person who could describe the origins of the data but fewer had documented that information.[3] If you have used historic data, think about how you found it and how you wish you might have been able to find it. Explore the concept and content of data papers and think about whether you might have some older data that you could describe in that same way. Talk to others about the topic and look for commonalities, especially across disciplines in your organization. Consult with the science librarians at your institution to see how you might work together. Finally, also think about your professional societies and how they might play a role.

Conclusions

Researchers across the sciences use older data in analog format, but little is known about how they learn of its existence or locate it. Over the last 50+ years, authors have expressed concern about its fate and noted challenges with its use. With the exception of the community of biodiversity researchers, there have been few large projects to address the preservation and findability of analog data and little interest expressed by government agencies, professional associations, and academic and research institutions that would be in a position to act on a broader scale. Best practices (including selection of metadata schema, developing a data dictionary, describing data collection methods) and policies developed to govern the preservation and dissemination of digital data could serve as an example for developments concerning analog data. In the digital realm, best practices are often developed by professional associations, both disciplinary and data-focused, as well as those who manage data repositories.

Abbreviations, acronyms, and initialisms

- C3S: Copernicus Climate Change Service

- DiSSCo: Distributed System of Scientific Collections

- ESA: Ecological Society of America

- GBIF: Global Biodiversity Information Facility

- I-DARE: International Data Rescue Portal

- iDigBio: Integrated Digitized Biocollections

- USDA: U.S. Department of Agriculture

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

All authors made significant contributions to the design of this review as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. All have approved this final version, agreed to be accountable, and have approved of the inclusion of those in the list of authors.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- ↑ "Data Refuge". University of Pennsylvania. 2022. https://www.datarefuge.org/.

- ↑ Farrell, Shannon L.; Hendrickson, Lois G.; Mastel, Kristen L.; Allen, Katherine Adina; Kelly, Julia A. (18 December 2019). "Resurfacing Historical Scientific Data: A Case Study Involving Fruit Breeding Data". Journal of eScience Librarianship 8 (2): e1171. doi:10.7191/jeslib.2019.1171. https://publishing.escholarship.umassmed.edu/jeslib/article/id/476/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Farrell, Shannon L.; Hendrickson, Lois G.; Mastel, Kristen L.; Kelly, Julia A. (15 December 2020). "Historical Scientific Analog Data: Life Sciences Faculty’s Perspectives on Management, Reuse and Preservation". Data Science Journal 19 (1): 51. doi:10.5334/dsj-2020-051. ISSN 1683-1470. https://datascience.codata.org/article/10.5334/dsj-2020-051/.

- ↑ Johnson, Richard W. (1 May 1964). "Retain the Original Data! Comment." (in en). American Psychologist 19 (5): 350–351. doi:10.1037/h0039238. ISSN 1935-990X. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/h0039238.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Craig, James R.; Reese, Sandra C. (1 August 1973). "Retention of raw data: A problem revisited." (in en). American Psychologist 28 (8): 723–723. doi:10.1037/h0035667. ISSN 1935-990X. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/h0035667.

- ↑ Wolins, Leroy (1 September 1962). "Responsibility for Raw Data." (in en). American Psychologist 17 (9): 657–658. doi:10.1037/h0038819. ISSN 1935-990X. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/h0038819.

- ↑ Buma, Brian (11 May 2018). Sills, Jennifer. ed. "The hidden value of paper records" (in en). Science 360 (6389): 613–613. doi:10.1126/science.aat5382. ISSN 0036-8075. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aat5382.

- ↑ Buma, B.; Bisbing, S. M.; Wiles, G.; Bidlack, A. L. (1 December 2019). "100 yr of primary succession highlights stochasticity and competition driving community establishment and stability" (in en). Ecology 100 (12). doi:10.1002/ecy.2885. ISSN 0012-9658. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ecy.2885.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Gross, K.L.; Pake, C.E. (1995). "Final report of the Ecological Society of America committee on the future of Long-term Ecological Data (FLED): Volume I: text of the report". The Ecological Society of America. pp. 122. https://andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/publications/2562.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 National Research Council (27 April 1995). Finding the Forest in the Trees: The Challenge of Combining Diverse Environmental Data. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/4896. ISBN 978-0-309-05082-1. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/4896.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 National Research Council (19 April 1995). Preserving Scientific Data on Our Physical Universe: A New Strategy for Archiving the Nation's Scientific Information Resources. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/4871. ISBN 978-0-309-05186-6. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/4871.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Easterday, Kelly; Paulson, Tim; DasMohapatra, Proxima; Alagona, Peter; Feirer, Shane; Kelly, Maggi (1 October 2018). "From the Field to the Cloud: A Review of Three Approaches to Sharing Historical Data From Field Stations Using Principles From Data Science". Frontiers in Environmental Science 6: 88. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2018.00088. ISSN 2296-665X. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00088/full.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Berman, J.J. (2015). Repurposing Legacy Data. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/c2014-0-02501-4. ISBN 978-0-12-802882-7. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/C20140025014.

- ↑ Elizabeth Griffin, R. (1 June 2015). "When are Old Data New Data?" (in en). GeoResJ 6: 92–97. doi:10.1016/j.grj.2015.02.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214242815000121.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Griffin, E. (2 July 2015). "Data at Risk and Data Rescue". CODATA Blog. https://codata.org/blog/2015/07/02/data-at-risk-and-data-rescue/.

- ↑ Patil, Chris; Siegel, Vivian (5 November 2009). "Shining a light on dark data" (in en). Disease Models & Mechanisms 2 (11-12): 521–525. doi:10.1242/dmm.004630. ISSN 1754-8411. PMC PMC2773820. PMID 19892880. https://journals.biologists.com/dmm/article/2/11-12/521/2278/Shining-a-light-on-dark-data.

- ↑ Singer, Randal A.; Ellis, Shari; Page, Lawrence M. (1 February 2020). "Awareness and use of biodiversity collections by fish biologists" (in en). Journal of Fish Biology 96 (2): 297–306. doi:10.1111/jfb.14167. ISSN 0022-1112. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jfb.14167.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Bowser, C.J. (1986). "Historic data sets: Lessons from the past, lessons for the future". In Michener, William K.; Belle W. Baruch Institute for Marine Biology and Coastal Research. Research data management in the ecological sciences. The Belle W. Baruch library in marine science (1st ed ed.). Columbia, S.C: Published for the Belle W. Baruch Institute for Marine Biology and Coastal Research by the University of South Carolina Press. pp. 155–79. ISBN 978-0-87249-476-3.

- ↑ Michener, William K.; Bildstein, Keith L.; McKee, Arthur; Parmenter, Robert R.; Hargrove, William W.; McClearn, Deedra; Stromberg, Mark (1 April 2009). "Biological Field Stations: Research Legacies and Sites for Serendipity" (in en). BioScience 59 (4): 300–310. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.4.8. ISSN 0006-3568. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article-lookup/doi/10.1525/bio.2009.59.4.8.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Beans, Carolyn (26 December 2018). "Journal entries, maps, and photos help ecologists reconstruct ecosystems of the past" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (52): 13138–13141. doi:10.1073/pnas.1819526115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC PMC6310833. PMID 30587550. https://pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1819526115.

- ↑ McCLENACHAN, Loren (1 June 2009). "Documenting Loss of Large Trophy Fish from the Florida Keys with Historical Photographs" (in en). Conservation Biology 23 (3): 636–643. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01152.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01152.x.

- ↑ McClenachan, Loren; Ferretti, Francesco; Baum, Julia K. (1 October 2012). "From archives to conservation: why historical data are needed to set baselines for marine animals and ecosystems" (in en). Conservation Letters 5 (5): 349–359. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00253.x. ISSN 1755-263X. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1755-263X.2012.00253.x.

- ↑ McClenachan, Loren; O’Connor, Grace; Neal, Benjamin P.; Pandolfi, John M.; Jackson, Jeremy B. C. (1 September 2017). "Ghost reefs: Nautical charts document large spatial scale of coral reef loss over 240 years" (in en). Science Advances 3 (9): e1603155. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1603155. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC PMC5587093. PMID 28913420. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1603155.

- ↑ Olson, D.; McCord, R. (August 1997). "Data Archival: Sharing Yesterday's Data for Ecology Today and Tomorrow". Data and Information Management in the Ecological Sciences. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. pp. 53–8. https://www.vcrlter.virginia.edu/dimes/presentations/OLSON/sld001.htm.

- ↑ Olson, R.J.; McCord, R.A. (2000). "Archiving ecological data and information". In Michener, William K.; Brunt, James W.. Ecological data: Design, management, and processing. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science. pp. 117–41. ISBN 978-0-632-05231-8.

- ↑ Kwok, Roberta (21 September 2017). "Historical data: Hidden in the past" (in en). Nature 549 (7672): 419–421. doi:10.1038/nj7672-419. ISSN 0028-0836. http://www.nature.com/articles/nj7672-419.

- ↑ Brönnimann, Stefan; Brugnara, Yuri; Allan, Rob J.; Brunet, Manola; Compo, Gilbert P.; Crouthamel, Richard I.; Jones, Philip D.; Jourdain, Sylvie et al. (1 June 2018). "A roadmap to climate data rescue services" (in en). Geoscience Data Journal 5 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1002/gdj3.56. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/gdj3.56.

- ↑ Diviacco, Paolo; Wardell, Nigel; Forlin, Edy; Sauli, Chiara; Burca, Mihai; Busato, Alessandro; Centonze, Jacques; Pelos, Claudio (1 June 2015). "Data rescue to extend the value of vintage seismic data: The OGS-SNAP experience" (in en). GeoResJ 6: 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.grj.2015.01.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214242815000078.

- ↑ Vearncombe, J.; Conner, G.; Bright, S. (1 October 2016). "Value from legacy data" (in en). Applied Earth Science 125 (4): 231–246. doi:10.1080/03717453.2016.1190442. ISSN 0371-7453. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03717453.2016.1190442.

- ↑ Vearncombe, Julian; Riganti, Angela; Isles, David; Bright, Sian (1 October 2017). "Data upcycling" (in en). Ore Geology Reviews 89: 887–893. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2017.07.009. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169136817305243.

- ↑ Clavero, Miguel; Revilla, Eloy (1 June 2014). "Bodiversity data: Mine centuries-old citizen science" (in en). Nature 510 (7503): 35–35. doi:10.1038/510035c. ISSN 0028-0836. http://www.nature.com/articles/510035c.

- ↑ Clavero, Miguel; Ninyerola, Miquel; Hermoso, Virgilio; Filipe, Ana Filipa; Pla, Magda; Villero, Daniel; Brotons, Lluís; Delibes, Miguel (11 January 2017). "Historical citizen science to understand and predict climate-driven trout decline" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284 (1846): 20161979. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1979. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC PMC5247491. PMID 28077766. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2016.1979.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Hof, Anouschka R.; Bright, Paul W. (1 August 2016). "Quantifying the long-term decline of the West European hedgehog in England by subsampling citizen-science datasets" (in en). European Journal of Wildlife Research 62 (4): 407–413. doi:10.1007/s10344-016-1013-1. ISSN 1612-4642. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10344-016-1013-1.

- ↑ Snäll, Tord; Kindvall, Oskar; Nilsson, Johan; Pärt, Tomas (1 February 2011). "Evaluating citizen-based presence data for bird monitoring" (in en). Biological Conservation 144 (2): 804–810. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.11.010. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006320710004805.

- ↑ Tallant, J.; Schell, J.; Hovinga, K.; Stuit, M. (2022). "Unearthing Michigan Ecological Data - FAQ". Zooniverse. https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/jmschell/unearthing-michigan-ecological-data/about/faq.

- ↑ Nelson, Gil; Ellis, Shari (7 January 2019). "The history and impact of digitization and digital data mobilization on biodiversity research" (in en). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374 (1763): 20170391. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0391. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC PMC6282090. PMID 30455209. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2017.0391.

- ↑ Patton, Bob; Nyren, Paul; Nyren, Ann; Sedivec, Kevin (2022), "27 years of livestock production data under different stocking rate levels at the Central Grasslands Research Extension Center near Streeter, North Dakota", Ag Data Commons, doi:10.15482/usda.adc/1524719, https://data.nal.usda.gov/node/86289

- ↑ "BHL Field Notes Project". Biodiversity Heritage Library. Smithsonian. 2022. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/collection/FieldNotesProject.

- ↑ "William B. Davis Collection". OAKTrust. Texas A&M University Libraries. 2022. https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/129120.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Thomer, Andrea; Vaidya, Gaurav; Guralnick, Robert; Bloom, David; Russell, Laura (20 July 2012). "From documents to datasets: A MediaWiki-based method of annotating and extracting species observations in century-old field notebooks". ZooKeys 209: 235–253. doi:10.3897/zookeys.209.3247. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC PMC3406479. PMID 22859891. http://zookeys.pensoft.net/articles.php?id=2909.

- ↑ Lannoo, Michael J.; Lang, Kenneth; Waltz, Tim; Phillips, Gary S. (1 April 1994). "An Altered Amphibian Assemblage: Dickinson County, Iowa, 70 Years after Frank Blanchard's Survey". American Midland Naturalist 131 (2): 311. doi:10.2307/2426257. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2426257?origin=crossref.

- ↑ Gent, Marty L.; Morgan, John W. (1 May 2007). "Changes in the stand structure (1975?2000) of coastal Banksia forest in the long absence of fire" (in en). Austral Ecology 32 (3): 239–244. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01667.x. ISSN 1442-9985. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01667.x.

- ↑ Hédl, Radim; Petřík, Petr; Boublík, Karel (1 October 2011). "Long-term patterns in soil acidification due to pollution in forests of the Eastern Sudetes Mountains" (in en). Environmental Pollution 159 (10): 2586–2593. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2011.06.014. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0269749111003423.

- ↑ Riddell, E. A.; Iknayan, K. J.; Hargrove, L.; Tremor, S.; Patton, J. L.; Ramirez, R.; Wolf, B. O.; Beissinger, S. R. (5 February 2021). "Exposure to climate change drives stability or collapse of desert mammal and bird communities" (in en). Science 371 (6529): 633–636. doi:10.1126/science.abd4605. ISSN 0036-8075. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abd4605.

- ↑ Trisurat, Yongyut; Eiadthong, Wichan; Khunrattanasiri, Weeraphart; Saengnin, Somyot; Chitechote, Auschada; Maneerat, Sompoch (1 September 2020). "Systematic forest inventory plots and their contribution to plant distribution and climate change impact studies in Thailand" (in en). Ecological Research 35 (5): 724–732. doi:10.1111/1440-1703.12105. ISSN 0912-3814. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1440-1703.12105.

- ↑ Azeria, Ermias T.; Carlson, Allan; Pärt, Tomas; Wiklund, Christer G. (1 July 2006). "Temporal dynamics and nestedness of an oceanic island bird fauna: Temporal dynamics and nestedness" (in en). Global Ecology and Biogeography 15 (4): 328–338. doi:10.1111/j.1466-822X.2006.00227.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1466-822X.2006.00227.x.

- ↑ Brodman, Robert; Cortwright, Spencer; Resetar, Alan (1 January 2002). "Historical Changes of Reptiles and Amphibians of Northwest Indiana Fish and Wildlife Properties" (in en). The American Midland Naturalist 147 (1): 135–144. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2002)147[0135:HCORAA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0031. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1674/0003-0031%282002%29147%5B0135%3AHCORAA%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

- ↑ Fellers, Gary M.; Drost, Charles A. (1993). "Disappearance of the cascades frog Rana cascadae at the southern end of its range, California, USA" (in en). Biological Conservation 65 (2): 177–181. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(93)90447-9. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0006320793904479.

- ↑ Curty, Renata Gonçalves; Crowston, Kevin; Specht, Alison; Grant, Bruce W.; Dalton, Elizabeth D. (27 December 2017). Sugimoto, Cassidy Rose. ed. "Attitudes and norms affecting scientists’ data reuse" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (12): e0189288. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189288. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC PMC5744933. PMID 29281658. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189288.

- ↑ Khan, Nushrat; Thelwall, Mike; Kousha, Kayvan (1 April 2021). "Measuring the impact of biodiversity datasets: data reuse, citations and altmetrics" (in en). Scientometrics 126 (4): 3621–3639. doi:10.1007/s11192-021-03890-6. ISSN 0138-9130. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11192-021-03890-6.

- ↑ Yoon, Ayoung; Kim, Youngseek (1 July 2017). "Social scientists' data reuse behaviors: Exploring the roles of attitudinal beliefs, attitudes, norms, and data repositories" (in en). Library & Information Science Research 39 (3): 224–233. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2017.07.008. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0740818816302250.

- ↑ Vines, Timothy H.; Albert, Arianne Y.K.; Andrew, Rose L.; Débarre, Florence; Bock, Dan G.; Franklin, Michelle T.; Gilbert, Kimberly J.; Moore, Jean-Sébastien et al. (1 January 2014). "The Availability of Research Data Declines Rapidly with Article Age" (in en). Current Biology 24 (1): 94–97. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.014. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982213014000.

- ↑ Gabelica, Mirko; Bojčić, Ružica; Puljak, Livia (1 October 2022). "Many researchers were not compliant with their published data sharing statement: a mixed-methods study" (in en). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 150: 33–41. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.05.019. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S089543562200141X.

- ↑ Cardinale, M; Bartolino, V; Svedäng, H; Sundelöf, A; Poulsen, R T; Casini, M (1 September 2015). "A centurial development of the North Sea fish megafauna as reflected by the historical Swedish longlining fisheries" (in en). Fish and Fisheries 16 (3): 522–533. doi:10.1111/faf.12074. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/faf.12074.

- ↑ Chauvel, Bruno; Guillemin, Jean-Philippe; Gasquez, Jacques; Gauvrit, Christian (1 December 2012). "History of chemical weeding from 1944 to 2011 in France: Changes and evolution of herbicide molecules" (in en). Crop Protection 42: 320–326. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2012.07.011. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0261219412002062.

- ↑ Edwards, Robert J.; Contreras-Balderas, Salvador (1 June 1991). "Historical Changes in the Ichthyofauna of the Lower Rio Grande (Rio Bravo del Norte), Texas and Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist 36 (2): 201. doi:10.2307/3671922. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3671922?origin=crossref.

- ↑ Chuine, Isabelle; Yiou, Pascal; Viovy, Nicolas; Seguin, Bernard; Daux, Valérie; Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy (1 November 2004). "Grape ripening as a past climate indicator" (in en). Nature 432 (7015): 289–290. doi:10.1038/432289a. ISSN 0028-0836. http://www.nature.com/articles/432289a.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Smith, Katherine L.; Jones, Michael L. (9 November 2007). "When are historical data sufficient for making watershed-level stream fish management and conservation decisions?" (in en). Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 135 (1-3): 291–311. doi:10.1007/s10661-007-9650-1. ISSN 0167-6369. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10661-007-9650-1.

- ↑ Llasat, María-Carmen; Barriendos, Mariano; Barrera, Antonio; Rigo, Tomeu (1 November 2005). "Floods in Catalonia (NE Spain) since the 14th century. Climatological and meteorological aspects from historical documentary sources and old instrumental records" (in en). Journal of Hydrology 313 (1-2): 32–47. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.02.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022169405000272.

- ↑ Ledneva, Anna; Miller-Rushing, Abraham J.; Primack, Richard B.; Imbres, Carolyn (1 September 2004). "CLIMATE CHANGE AS REFLECTED IN A NATURALIST'S DIARY, MIDDLEBOROUGH, MASSACHUSETTS" (in en). The Wilson Bulletin 116 (3): 224–231. doi:10.1676/04-016. ISSN 0043-5643. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1676/04-016.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Agriculture (July 1993). "Snapshot in Time, Repeat Photography on the Boise National Forest 1870-1992". U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/2.

- ↑ Rogers, Garry F.; Malde, Harold E.; Turner, R. M. (1984). Bibliography of repeat photography for evaluating landscape change. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-239-9.

- ↑ Webb, Robert H.; Boyer, Diane E.; Turner, R. M., eds. (2010). Repeat photography: methods and applications in the natural sciences. Washington: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-59726-712-0.

- ↑ Primack, Richard B.; Miller-Rushing, Abraham J. (1 February 2012). "Uncovering, Collecting, and Analyzing Records to Investigate the Ecological Impacts of Climate Change: A Template from Thoreau's Concord" (in en). BioScience 62 (2): 170–181. doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.10. ISSN 1525-3244. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article-lookup/doi/10.1525/bio.2012.62.2.10.

- ↑ Lescrauwaet, A.-C. (2013). Belgian fisheries: Ten decades, seven seas, forty species: Historical time-series to reconstruct landings, catches, fleet and fishing areas from 1900. Ghent University Faculty of Sciences. pp. 256. ISBN 9789082073119. http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-4143013.

- ↑ Brázdil, Rudolf; Chromá, Kateřina; Valášek, Hubert; Dolák, Lukáš; Řezníčková, Ladislava (1 January 2016). "Damaging hailstorms in South Moravia, Czech Republic, in the seventeenth to twentieth centuries as derived from taxation records" (in en). Theoretical and Applied Climatology 123 (1-2): 185–198. doi:10.1007/s00704-014-1338-1. ISSN 0177-798X. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00704-014-1338-1.

- ↑ Van der Veken, Sebastiaan; Verheyen, Kris; Hermy, Martin (1 January 2004). "Plant species loss in an urban area (Turnhout, Belgium) from 1880 to 1999 and its environmental determinants" (in en). Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants 199 (6): 516–523. doi:10.1078/0367-2530-00180. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0367253005701407.

- ↑ Martin, Kathy; Brown, Graeme A.; Young, Jessica R. (1 July 2004). "The historic and current distribution of the Vancouver Island White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lagopus leucurus saxatilis)" (in en). Journal of Field Ornithology 75 (3): 239–256. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-75.3.239. ISSN 0273-8570. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1648/0273-8570-75.3.239.

- ↑ Sharma, Sapna; Magnuson, John J.; Batt, Ryan D.; Winslow, Luke A.; Korhonen, Johanna; Aono, Yasuyuki (26 April 2016). "Direct observations of ice seasonality reveal changes in climate over the past 320–570 years" (in en). Scientific Reports 6 (1): 25061. doi:10.1038/srep25061. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC PMC4844970. PMID 27113125. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep25061.

- ↑ Kelso, Clare; Vogel, Coleen (27 June 2007). "The climate of Namaqualand in the nineteenth century" (in en). Climatic Change 83 (3): 357–380. doi:10.1007/s10584-007-9264-1. ISSN 0165-0009. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10584-007-9264-1.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Wiebe, Peter H.; Allison, M. Dickson (1 June 2015). "Bringing dark data into the light: A case study of the recovery of Northwestern Atlantic zooplankton data collected in the 1970s and 1980s" (in en). GeoResJ 6: 195–201. doi:10.1016/j.grj.2015.03.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214242815000273.

- ↑ Pullin, Andrew S.; Salafsky, Nick (19 February 2010). "Save the Whales? Save the Rainforest? Save the Data!: Editorial" (in en). Conservation Biology 24 (4): 915–917. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01537.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01537.x.

- ↑ Duckworth, Steve; Mack, Grayce; Thornhill, Kate (30 August 2022). The Trouble with Legacy Public Health Data. Open Science Framework. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/UJHN2. https://osf.io/ujhn2/.

- ↑ Curry, Andrew (11 February 2011). "Rescue of Old Data Offers Lesson for Particle Physicists" (in en). Science 331 (6018): 694–695. doi:10.1126/science.331.6018.694. ISSN 0036-8075. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.331.6018.694.

- ↑ Downs, Robert R.; Chen, Robert S. (2017). "Curation of Scientific Data at Risk of Loss: Data Rescue and Dissemination". Curating research data: Volume one: Practical strategies for your digital repository (Association of College and Research Libraries): 275–94. doi:10.7916/D8W09BMQ. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8W09BMQ.

- ↑ Wicherts, Jelte M.; Borsboom, Denny; Kats, Judith; Molenaar, Dylan (2006). "The poor availability of psychological research data for reanalysis." (in en). American Psychologist 61 (7): 726–728. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.726. ISSN 1935-990X. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.726.

- ↑ Sheffield, C.; Nakasone, S.; Ferrante, R. et al. (2011). "Merging Metadata: Building on Existing Standards to Create a Field Book Registry". LIBREAS. Library Ideas 18. https://libreas.eu/ausgabe18/texte/08sheffield.htm.

- ↑ Loehle, Craig; Weatherford, Philip (1 October 2017). "Detecting population trends with historical data: Contributions of volatility, low detectability, and metapopulation turnover to potential sampling bias" (in en). Ecological Modelling 362: 13–18. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2017.08.021. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0304380017303794.

- ↑ Magurran, Anne E.; Baillie, Stephen R.; Buckland, Stephen T.; Dick, Jan McP.; Elston, David A.; Scott, E. Marian; Smith, Rognvald I.; Somerfield, Paul J. et al. (1 October 2010). "Long-term datasets in biodiversity research and monitoring: assessing change in ecological communities through time" (in en). Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25 (10): 574–582. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.016. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169534710001552.

- ↑ Reznick, David; Baxter, Ronald J.; Endler, John (1 June 1994). "Long-term Studies of Tropical Stream Fish Communities:The Use of Field Notes and Museum Collections to Reconstruct Communities of the Past" (in en). American Zoologist 34 (3): 452–462. doi:10.1093/icb/34.3.452. ISSN 0003-1569. https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/icb/34.3.452.

- ↑ Knapp, Kenneth R.; Bates, John J.; Barkstrom, Bruce (1 September 2007). "Scientific Data Stewardship: Lessons Learned from a Satallite–Data Rescue Effort" (in en). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 88 (9): 1359–1362. doi:10.1175/BAMS-88-9-1359. ISSN 0003-0007. https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/BAMS-88-9-1359.

- ↑ Löffler, Felicitas; Wesp, Valentin; König-Ries, Birgitta; Klan, Friederike (24 March 2021). Suleman, Hussein. ed. "Dataset search in biodiversity research: Do metadata in data repositories reflect scholarly information needs?" (in en). PLOS ONE 16 (3): e0246099. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246099. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC PMC7990268. PMID 33760822. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246099.

- ↑ Sprague, Lori A.; Oelsner, Gretchen P.; Argue, Denise M. (1 March 2017). "Challenges with secondary use of multi-source water-quality data in the United States" (in en). Water Research 110: 252–261. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2016.12.024. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0043135416309642.

- ↑ Kéry, Marc; Spillmann, John H.; Truong, Camille; Holderegger, Rolf (1 September 2006). "How biased are estimates of extinction probability in revisitation studies?" (in en). Journal of Ecology 94 (5): 980–986. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01151.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2006.01151.x.

- ↑ Pollock, Jacob F. (1 June 2006). "Detecting Population Declines over Large Areas with Presence-Absence, Time-to-Encounter, and Count Survey Methods" (in en). Conservation Biology 20 (3): 882–892. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00342.x. ISSN 0888-8892. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00342.x.

- ↑ Rivadeneira, Marcelo M.; Hunt, Gene; Roy, Kaustuv (1 May 2009). "The use of sighting records to infer species extinctions: an evaluation of different methods" (in en). Ecology 90 (5): 1291–1300. doi:10.1890/08-0316.1. ISSN 0012-9658. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1890/08-0316.1.

- ↑ Huisman, John M.; Millar, Alan J.K. (1 January 2013). "Australian seaweed collections: use and misuse" (in en). Phycologia 52 (1): 2–5. doi:10.2216/12-089.1. ISSN 0031-8884. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2216/12-089.1.

- ↑ Kullman, Leif (1 August 2010). "Alpine flora dynamics - a critical review of responses to climate change in the Swedish Scandes since the early 1950s" (in en). Nordic Journal of Botany 28 (4): 398–408. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2010.00812.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1756-1051.2010.00812.x.

- ↑ Engelhard, Georg H.; Righton, David A.; Pinnegar, John K. (1 August 2014). "Climate change and fishing: a century of shifting distribution in North Sea cod" (in en). Global Change Biology 20 (8): 2473–2483. doi:10.1111/gcb.12513. ISSN 1354-1013. PMC PMC4282283. PMID 24375860. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12513.

- ↑ Schulte, L.A.; Mladenoff, D.J. (2001). "The Original US Public Land Survey Records: Their Use and Limitations in Reconstructing Presettlement Vegetation". Journal of Forestry 99 (10): 5–10. doi:10.1093/jof/99.10.5. https://academic.oup.com/jof/article/99/10/5/4614271.

- ↑ Delisle, Fanny; Lavoie, Claude; Jean, Martin; Lachance, Daniel (1 July 2003). "Reconstructing the spread of invasive plants: taking into account biases associated with herbarium specimens: Invasive plants and herbarium specimens" (in en). Journal of Biogeography 30 (7): 1033–1042. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00897.x. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00897.x.

- ↑ Bavel, Bas J. P.; Curtis, Daniel R.; Hannaford, Matthew J.; Moatsos, Michail; Roosen, Joris; Soens, Tim (1 November 2019). "Climate and society in long‐term perspective: Opportunities and pitfalls in the use of historical datasets" (in en). WIREs Climate Change 10 (6). doi:10.1002/wcc.611. ISSN 1757-7780. PMC PMC6852122. PMID 31762795. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.611.

- ↑ Faniel, Ixchel M.; Frank, Rebecca D.; Yakel, Elizabeth (26 September 2019). "Context from the data reuser’s point of view" (in en). Journal of Documentation 75 (6): 1274–1297. doi:10.1108/JD-08-2018-0133. ISSN 0022-0418. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JD-08-2018-0133/full/html.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The original organizes references in alphabetical order; this version organizes them by order of appearance, by design. Several inline URLs in the original were turned into formal citations for this version.