Journal:Understanding cybersecurity frameworks and information security standards: A review and comprehensive overview

| Full article title | Understanding cybersecurity frameworks and information security standards: A review and comprehensive overview |

|---|---|

| Journal | Electronics |

| Author(s) | Taherdoost, Hamed |

| Author affiliation(s) | University Canada West |

| Primary contact | Email: hamed dot taherdoost at gmail dot com |

| Year published | 2022 |

| Volume and issue | 11(14) |

| Article # | 2181 |

| DOI | 10.3390/electronics11142181 |

| ISSN | 2079-9292 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/11/14/2181 |

| Download | https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/11/14/2181/pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Businesses are reliant on data to survive in the competitive market, and data is constantly in danger of loss or theft. Loss of valuable data leads to negative consequences for both individuals and organizations. Cybersecurity is the process of protecting sensitive data from damage or theft. To successfully achieve the objectives of implementing cybersecurity at different levels, a range of procedures and standards should be followed. Cybersecurity standards determine the requirements that an organization should follow to achieve cybersecurity objectives and minimize the impact of cybercrimes. Cybersecurity standards demonstrate whether an information management system can meet security requirements through a range of best practices and procedures. A range of standards has been established by various organizations to be employed in information management systems of different sizes and types. However, it is challenging for businesses to adopt the standard that is the most appropriate based on their cybersecurity demands. Reviewing the experiences of other businesses in the industry helps organizations to adopt the most relevant cybersecurity standards and frameworks.

This study presents a narrative review of the most frequently used cybersecurity standards and frameworks based on 1. existing papers in the cybersecurity field and 2. applications of these cybersecurity standards and frameworks in various fields to help organizations select the cybersecurity standard or framework that best fits their cybersecurity requirements.

Keywords: cybersecurity framework, cybersecurity standard, information security framework, information security standard, cybersecurity requirements, information security requirements, narrative review

Introduction

A standard is described as an ideal condition with a minimum achievement limit.[1] It also refers to technical specifications that are required to be applied by a service facility to enable service users to acquire the maximum function, purpose, or profit from the services.[2] Many international organizations, associations, and consortia have a vital role in the development of standards.[3][4] According to Standards Australia[5], standards are represented as documents which define specifications, procedures, and guidelines, aiming to ensure safety, consistency, and reliability of products, services, and systems. Moreover, based on the provided definition by the International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC), standards are documents or rules made based on a general agreement and validated by a legal entity, which help to achieve optimal results, as a guideline, model, or sample, in a particular context.[6] A standard practically meets user demands, considers the limitations of technology and resources, and also meets the verification requirements.[2]

The term "standard" most commonly refers to established documents by professional bodies to be used by other organizations (i.e., technical standards, program standards), or standards of technical practice (i.e., practical cybersecurity standards).

The sets of practices or technical methods that help organizations to secure their cyber environment are referred to as cybersecurity standards.[7] Cybersecurity standards include users, network infrastructure, software, hardware, processes, and information in system storage media that can be connected to the internet.[7] The scope of cybersecurity standards is broad in that it covers security features in applications and cryptographic algorithms that mainly provide perspective toward security controls, processes, procedures, guidelines, and baselines.[8] Security experts recommend implementing cybersecurity standards as a fundamentally essential element consisting of a collection of best practices to protect organizations from cybersecurity threats and risks.[9]

The main aim of cybersecurity standards is to prevent or mitigate cyberattacks and reduce the risk of cyber threats.[10] The implementation of such standards typically benefits the adopter by saving time, decreasing costs, increasing profits, improving user awareness, minimizing risks, and offering business continuity.[8] Additionally, using standards facilitates the compliance of an organization to industry best practices and procedures and provides the opportunity to compare a security system on an international level.[11] Hence, the application of cybersecurity standards has been established in different organizations or businesses to protect assets against cyber threats.[12][13] As a result, different cybersecurity standards have been developed by various organizations to ensure that organizations of different size and nature implement appropriate measures to prevent and mitigate cyber threats.[14] However, since a considerable number of standards have been developed to cover different aspects of cybersecurity in various organizations, it may be challenging for business owners to choose the appropriate standard that is the best match for their business.[15]

This study aims to provide an overview of the most frequently used cybersecurity standards based on existing papers in the cybersecurity field, clarifying their features and applications in different industries. A wide range of cybersecurity standards and frameworks are available to ensure the protection of data in different industries; however, this review paper aims to provide a comparative concept regarding cybersecurity standards and frameworks and facilitate the selection of the most appropriate standards and frameworks. This paper can be also helpful for academic purposes to determine the direction of further studies in this field.

In the next section, an overview of the most common cybersecurity standards and frameworks is provided. Following that is a narrative literature review that is the result of extracting and analyzing 17 papers published about cybersecurity standards between 2000 to 2022, and then considering the aim of each study, the main findings of the research, as well as relevant industry and employed standards. Finally, a concluding discussion is presented that clarifies the contribution of different standards for specific purposes.

Cybersecurity standards and frameworks

Cybersecurity standards are generally classified into two main categories: information security standards and information security governance standards.[16] Information security standards and frameworks such as the ISO/IEC 27000 series, ISF SOGP, NIST 800 series, SOX, and Risk IT mainly concentrate on security concerns. Selecting the most appropriate standard or framework is a serious decision that should be made based on the requirements of the organization to examine if it adequately suits the demands of the business. In some cases, employment of a single standard does not suffice to meet the expectations of a business. Thus, managers need to examine whether they need to consider more than one standard or framework.[2]

Open standards and frameworks are easily available and optional to be employed. Thus, organizations can use some parts or all of the guidelines, as required, or use them in combination, integrated with other standards, to complement and strengthen other requirements.[17] Performance standards can be a policy or law to be complied with by certain countries. They may also be required by the responsible organization, association, or regulatory body to be complied with by the implementing organization.[18] A country or company is authorized to reject rules or standards published by others, or to develop their own proprietary standards or local regulatory standards.[19]

The effective implementation of cybersecurity standards as guidelines or techniques which include best practices to be used in business or industry is not possible without the employment of the relevant cybersecurity framework.[20][21] Cybersecurity standards explain and provide methods one by one, specify what is expected to be done to complete the process, and clarify methods to coincide with the standard; a cybersecurity framework is a general guideline that covers many components or domains that can be adopted by businesses/companies/institutions, which doesn't necessarily specify the steps that are required to be taken.[22] Satisfactory cybersecurity protection can be achieved by adopting a cybersecurity framework that describes the scope, implementation, and evaluation processes, and also provides a general structure and methodology for protecting critical digital assets.[23] In fact, organizations can refer to cybersecurity frameworks to realize guidelines in the successful implementation of cybersecurity standards to be better equipped to identify, detect, and respond to cyberattacks.[24]

Cybersecurity frameworks are flexible and can provide users with the freedom to choose some parts or the whole model, methods, or technical practices, offering general and adoptable guidelines, as well as offering suggestions to be applied within the organization.[25] Implementation costs can be reduced as a result of the flexibility of cybersecurity frameworks. This can be effective to protect the infrastructure against cyber threats and secure critical sectors in the nation and economy. Therefore, cybersecurity frameworks have been developed by academic institutions, international organizations, countries, and corporations to ensure cyber resilience.[26] Businesses that seek to successfully implement cybersecurity standards are dependent on cybersecurity frameworks to harmonize policy, business, and technological approaches that are effective to mitigate cybersecurity issues and address cyber risks.[27] Thus, to ensure the protection of data and the infrastructure in organizations, businesses, and governments, cybersecurity standards and frameworks are required.[28]

The difference between a standard and a framework is summarized in Table 1.

| ||||||

Cybersecurity and information security standards

Cybersecurity standards, as key parts of IT governance, are consulted to ensure that an organization is following its policies and strategy in cybersecurity.[3] Therefore, by relying on cybersecurity standards, an organization can turn its cybersecurity policies into measurable actions. Cybersecurity standards clarify functional and assurance steps that should be taken to achieve the objectives of the organization in terms of cybersecurity. It may seem costly for a business to invest in the implementation of cybersecurity standards; however, the confidence and trust that it brings are more beneficial for the organization.[29]

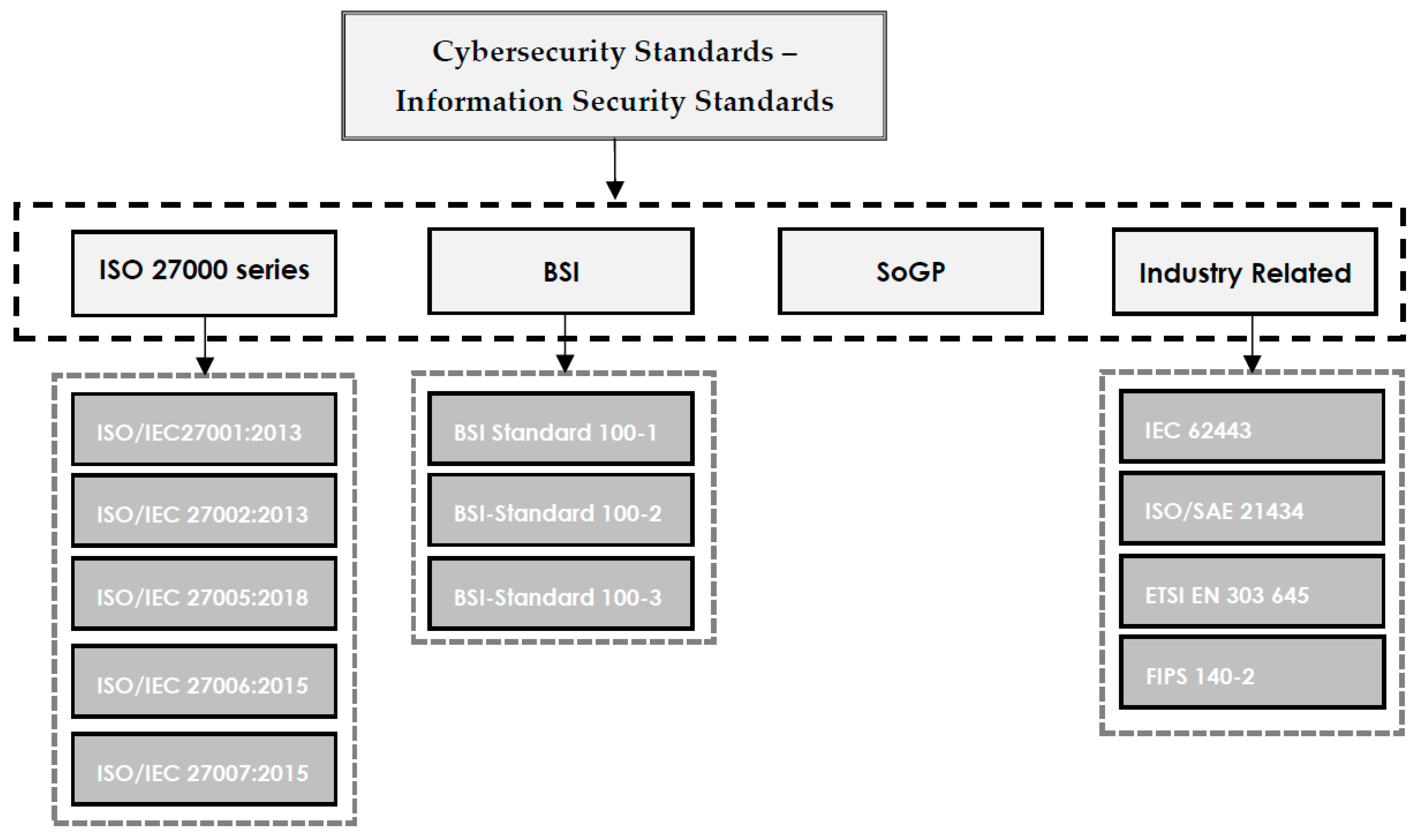

Written cybersecurity standard documents describe requirements to be respected by the organization and are easy to be controlled by stakeholders or relevant auditors. However, standards do not include how to achieve the standard requirements. The most popular and frequently used cybersecurity standards, referred to in this paper, are shown in Figure 1. It is important to note that cybersecurity frameworks may not be limited to what is presented in the scope of this study, since new frameworks are constantly being published based on demands. In a general classification, the ISO 27000 series, BSI, and SoGP are provided. Additionally, some standards that are common in industry are presented in the "Industry Related" category.

|

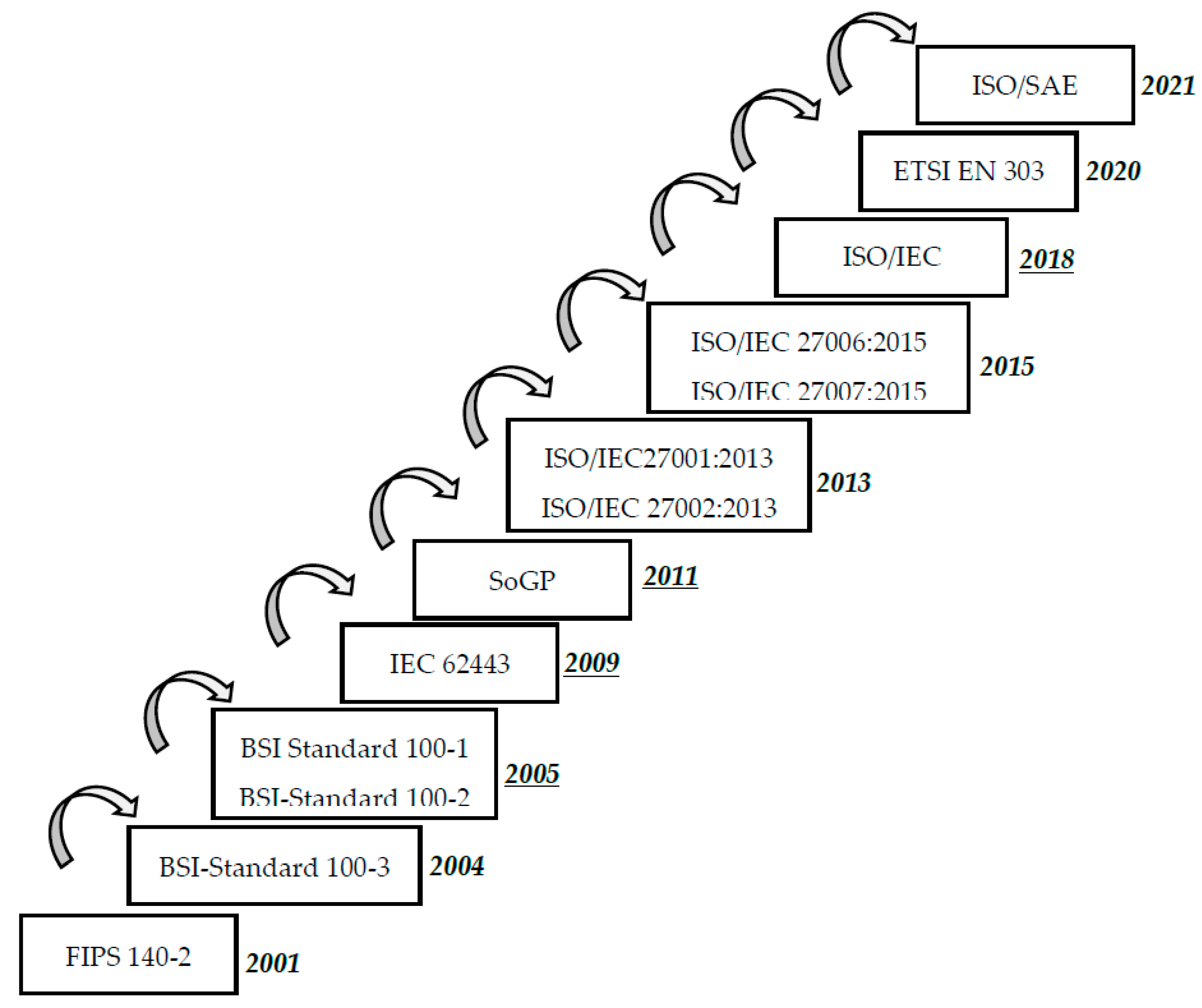

The evolution of cybersecurity standards over time is represented in Figure 2.

|

In the following subsections, the most popular cybersecurity standards—including the ISO 27000 series, SoGP, and BSI—are described to provide an overview and facilitate the process of decision-making.

ISO/IEC 27000 standards

The ISO/IEC 27000 series of standards concentrates on security in information systems management (ISM).[16] The family of ISO/IEC 27000 standards was initially recognized as BS7799 and then introduced as ISO standards as soon as the ISO added it to the information security management system (ISMS) standards.[30] Methods and practices to ensure effective implementation of information security in an organization are described in detail in ISO 27001, focusing on providing a secure and trustable exchange of data and communication channels. The main consideration of ISO 27001 in accomplishing managerial and organizational objectives and sub-objectives is through stressing the imporatance of risk management approaches. However, the ISO 27000 series has not been shown to successfully work as a complete information systems management (ISM) solution to be integrated into larger systems. ISO 27001, the first in the series of ISO/IEC 27000 standards, dates back to 2005. However, four standards, including 27001, 27002, 27005, and 27006, are currently published and widely used in organizations.[31]

ISO/IEC 27001:2013

ISO/IEC 27001:2013 is an internationally recognized standard that determines requirements to implement a certified ISMS for a business through seven key elements.[11] These steps include specifications for installation, performance, operation, controlling and monitoring, review, maintenance, and improvement of the system. General requirements for the treatment and assessment of risks that exist in the information system of the organizations are also included, regardless of the size, type, and nature of the business. ISO/IEC 27001 is commonly used along with ISO/IEC 27002, which clarifies security control objectives and recommendations, since it does not list specific security controls. Employment of ISO/IEC 27001 helps organizations to manage and protect the valuable information of employees and clients, manage information risks, and protect and develop their brands.[32] (Note that since the original publishing of this journal article, the standard was updated, in October 2022.)

ISO/IEC 27002:2013

ISO/IEC 27002:2013 is the code of practice for information security controls that lists a structured series of information security controls to comply with ISO/IEC 27001. However, security controls that are not specifically mentioned in this list are not mandatory to be employed by organizations. Best practice recommendations to be used by responsible individuals when they try to implement information security management are provided in ISO/IEC 27002.[33] This includes managing assets in an organization, securing human resources, managing operations and communications, securing environmental and physical aspects, managing business continuity, and managing compliance and information security incident areas.[26] (Note that since the original publishing of this journal article, the standard was updated, in February 2022.)

ISO/IEC 27005:2018

Guidelines for risk-based implementation of cybersecurity risk management are provided in ISO/IEC 27005:2018. The standard supports concepts and requirements that are specifically listed in ISO/IEC 27001. To completely understand ISO/IEC 27005, organizations need to gain knowledge about the processes and concepts of ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27002. ISO/IEC 27005 can be applicable to those implementing a satisfactory risk-based information system in organizations of different sizes and sectors.[34] ISO/IEC 27005 employs an information risk management process that consists of seven main elements, including installation of context, assessing risk, treating risk, accepting risk, communicating risk, consulting risk, as well as monitoring risk and reviewing risk.[26] (Note that since the original publishing of this journal article, the standard was updated, in October 2022.)

ISO/IEC 27006:2015

The main purpose of ISO/IEC 27006 is to determine formal processes and requirements that should be respected by third-party bodies that provide information security auditing and certifying services for other organizations. Conforming to ISO/IEC 27006 helps bodies to be recognized as trustable and reliable organizations operating ISMS.[11]

Other ISO/IEC standards

Other cybersecurity and information security standards put forth by the ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 27 technical committee include[26]:

- ISO/IEC 27000:2018 Information technology — Security techniques — Information security management systems — Overview and vocabulary

- ISO/IEC 27003:2017 Information technology — Security techniques — Information security management systems — Guidance

- ISO/IEC 27004:2016 Information technology — Security techniques — Information security management — Monitoring, measurement, analysis and evaluation

- ISO/IEC 27007:2020 Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection — Guidelines for information security management systems auditing

- ISO/IEC TS 27008:2019 Information technology — Security techniques — Guidelines for the assessment of information security controls

- ISO/IEC 27009:2020 Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection — Sector-specific application of ISO/IEC 27001 — Requirements

- ISO/IEC 27011:2016 Information technology — Security techniques — Code of practice for Information security controls based on ISO/IEC 27002 for telecommunications organizations

- ISO/IEC 27013:2021 Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection — Guidance on the integrated implementation of ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 20000-1

- ISO/IEC 27014:2020 Information security, cybersecurity and privacy protection — Governance of information security

- ISO/IEC TR 27016:2014 Information technology — Security techniques — Information security management — Organizational economics

- ISO/IEC 27017:2015 Information technology — Security techniques — Code of practice for information security controls based on ISO/IEC 27002 for cloud services

- ISO/IEC 27018:2019 Information technology — Security techniques — Code of practice for protection of personally identifiable information (PII) in public clouds acting as PII processors

- ISO/IEC 27019:2017 Information technology — Security techniques — Information security controls for the energy utility industry

ISF's Standard of Good Practice for Information Security

the Information Security Forum (ISF), an international organization based in London, with staff in New York City, initially published the Standard of Good Practice for Information Security in 1996. The ISF is a non-profit and independent organization that concentrates on the development of best practices and benchmarking in the information security arena.[8] Companies and individuals in manufacturing, financial services, transportation, chemical/pharmaceutical, retail, government, telecommunications, media, transportation, energy, and professional services from all over the world can join the ISF. The standard—which includes best practices in cybersecurity—is also revised every two years to cover the most recent best practices in information security. The standard is mainly designed to concentrate on six major aspects, including installing computers, application of critical business processes, managing security and networks, developing systems, and securing the environment for the end user.[2]

BSI's IT-Grundschutz Compendium and 200-X Standards

The German Federal Office for Information Security (Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik or BSI) is responsible for managing the security of computers and communication for the German government, focusing on security of computer applications, cryptography, internet security, security products, and security test laboratories.[11] Through its focus on "IT baseline protection" or IT-Grundschutz, BSI has provided recommendations for approaches, processes, methods, and procedures that are related to cybersecurity in its IT-Grundschutz Compendium, as well as its 200-X series of standards. It also covers key areas in information security that are required to be considered while setting approaches for companies and public authorities.[35]

BSI-Standard 200-1: Information Security Management Systems (ISMS)

The first standard in the BSI Standards 200-X series is BSI-Standard 200-1, which describes the main requirements that should be followed to implement ISMSs. There is full compatibility between 200-1 and ISO/IEC 27001. Moreover, recommendations and solutions of ISO standards are taken into consideration in this standard.[11] This standard mainly concentrates on managing the challenges of planning the information technology implementation process described in the ISO/IEC 27001 standard.[36]

BSI-Standard 200-2: IT-Grundschutz-Methodology

BSI-Standard 200-2 includes the employment of IT security management practices in a practical step-by-step manner, covering suggestions for the selection of appropriate measures in information technology security, the implementation of information technology security, and the intricacies of information technology security using the IT-Grundschutz methodologies of standard, basic, and core protection. Additionally, general requirements to employ ISO 27001, 27002 and 13335 standards are interpreted using notes and examples, which help facilitate the establishment of a successful ISMS.[35][37]

BSI-Standard 200-3: Risk Analysis based on IT-Grundschutz

BSI-Standard 200-3 concentrates on risk analysis. Organizations apply this approach to promote their risk analysis while they implement the IT-Grundschutz methodologies.[35] The elementary threats described in the IT-Grundschutz Compendium form the basis of the recommended information security risk analysis procedures of 200-3.[38]

Apart from the general classification of cybersecurity standards, a class of cybersecurity standards focusing on their application to specific business industries—including ISA/IEC 62443, ISO/SAE 21434, ETSI EN 303 645, and FIPS 140-3—is also provided in this study.

ISA/IEC 62443 standards

ISA/IEC 62443 is an international series of standards in cybersecurity that is focused on the employment of cybersecurity requirements for operating technology in systems used for industrial automation and control system (IACS) purposes.[39] This series of standards, initially established by the ISA99 committee, addresses current and future cybersecurity concerns in IACSs. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) has adopted this standard and asks security experts in industrial automation and control systems from all over the world to help develop the standard.[39] Since the standard has divided cybersecurity topics into different categories, it is not limited to the technology sector, and it also considers mitigating cyber threats regarding processes, employees, and countermeasures.

ISO/SAE 21434:2021

This standard is focused on cybersecurity risk management requirements in the engineering of electronic systems of road vehicles and includes production, operation, development, maintenance, etc. concepts in vehicular engineering.[40] It also expands into addressing both components and interfaces of road vehicles. The main aim of this standard is to ensure that cybersecurity concerns are addressed in the engineering of road vehicles and that they are protected against different cyberattacks.[40]

ETSI EN 303 645 V2.1.1

Cybersecurity is becoming a growing challenge, as more devices are connected to the internet and more people are sharing their personal data using internet of things (IoT) technologies. This standard targets all parties that are involved in manufacturing and developing IoT products and appliances.[41] The standard has collected a wide range of best practices and requirements in internet-connected products and appliances to ensure the security of consumers’ data. The main focus of this standard is on the establishment of organizational policies and technical controls that are applicable to all IoT devices.[41]

FIPS 140-3

The Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) are published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). This standard includes hardware and software requirements to protect cryptography modules. Cryptography modules include valuable information that should be secured with respect to integrity and confidentiality concerns. Four security levels, from the lowest to the highest, are defined in FIPS 140-3. This standard is established based on the joint collaboration of NIST and the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security to ensure that cryptographic modules meet validation requirements. Therefore, if a product meets FIPS 140-3 requirements, it is accepted by federal agencies of the United States and Canada at the same time.[42][43]

Cybersecurity and information security frameworks and supporting documents

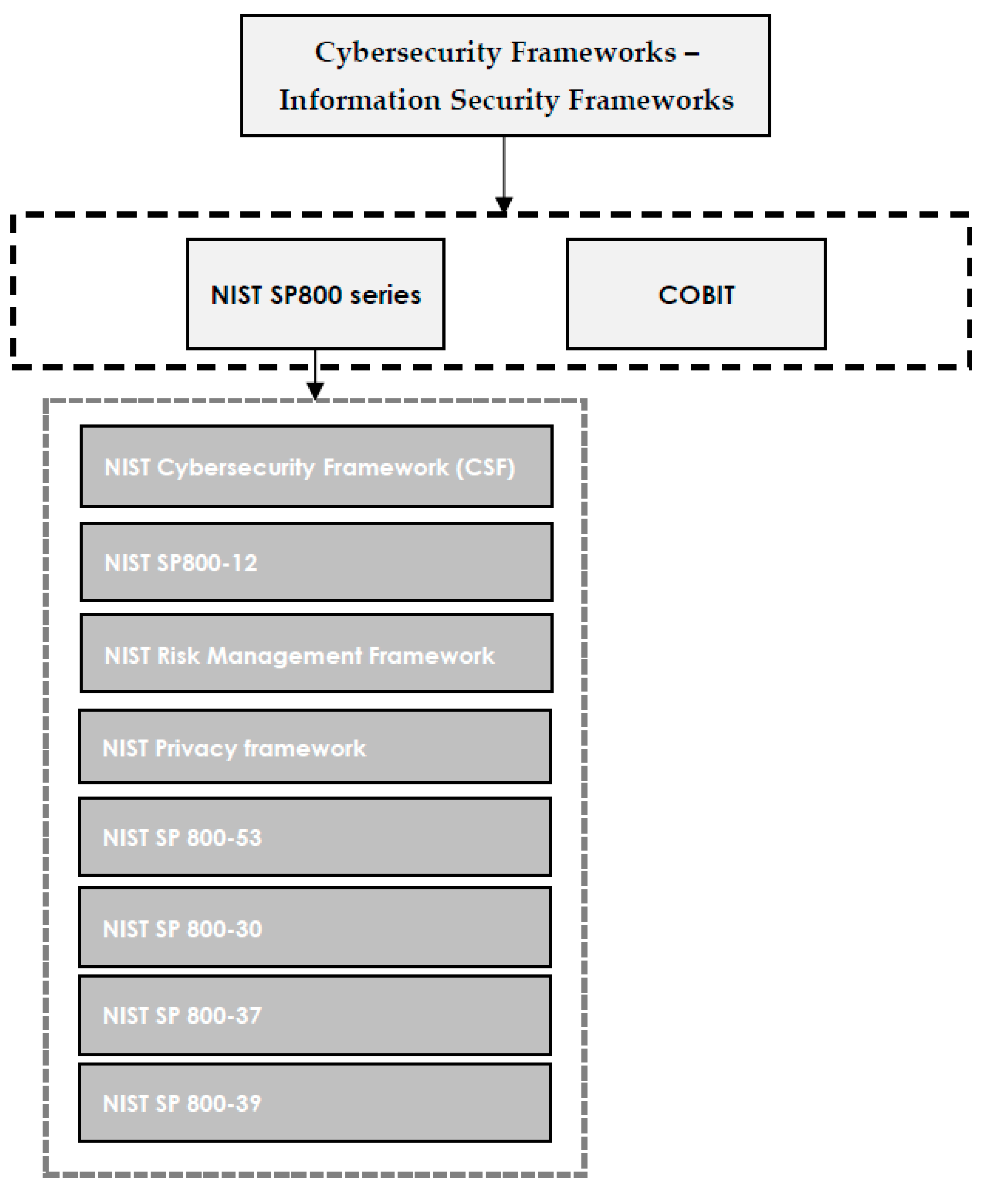

The cybersecurity framework is the structure that an organization needs with respect to becoming protected against cyberattacks. Some cybersecurity frameworks are mandatory and others are often strongly encouraged by regulators.[26] Thus, frameworks guide organizations in the implementation process to meet standard requirements. The main goal of a cybersecurity framework is to reduce the risk of cyber threats through learning from the best practices.[3] The most popular and frequently used cybersecurity frameworks and supporting documents that are referred to in this paper are shown in Figure 3. It is important to note that cybersecurity frameworks may not be limited to what is presented in the scope of this study, since new frameworks are constantly being published based on demands.

|

The NIST SP 800-X series

NIST is a non-regulatory federal agency established within the U.S. Department of Commerce that was founded in 1901, and its mission is to improve life and economic security through the development of technology, science, and standards.[11] Industries that are supported by NIST standards and measurements include building and fire research, chemical science and technology, information technology, electronics and electrical engineering, materials science and engineering, technology services, manufacturing engineering, physics, neutron research, and nanoscale science and technology.[44]

NIST defines the NIST SP 800-X series as a series of publications that report on the NIST "Information Technology Laboratory’s research, guidelines, and outreach efforts in computer security, and its collaborative activities with industry, government, and academic organizations."[45] It began publishing the SP 800-X series of documents in 1990, which is considered the oldest publications among its information security standards, covering a wide range of documents that support different aspects of information security.[8] The publications include recommendations, guidelines, technical features, and reports that NIST publishes annually about its cybersecurity activities. The SP 800-X series was initially developed to address privacy and security requirements in federal information systems; however, it was later used by non-federal organizations as well. To employ the publication for national security systems, it is mandatory to get approval from the relevant federal authority.[46] Popular NIST SP 800-X documents include:

- SP 800-12, Rev. 1 An Introduction to Information Security

- SP 800-30, Rev. 1 Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments

- SP 800-37, Rev. 2 Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy

- SP 800-39 Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View

- SP 800-53, Rev. 5 Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations

NIST SP 800-12, Rev. 1 has been one of the more popular documents in this series, since it offers a good perspective of the NIST approach.[11] However, SP 800-53, Rev. 5 and ancillary frameworks such as the NIST Cybersecurity Framework play critical roles for many organizations today.[47]

Outside the SP 800-X series of documents, NIST also provides complementary information security and cybersecurity works, including the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, NIST Privacy Framework, and NIST Risk Management Framework (RMF).

SP 800-12, Rev. 1

The core principles of cybersecurity are covered in detail in NIST SP 800-12.[11] It was initially developed to be used in governmental and federal agencies; however, it can also be employed in other organizations focusing on computer security and controls.[8] The broad approach of the NIST is characterized in NIST SP 800-12, clarifying the main elements, including the role of computer security in supporting the mission of the business, emphasizing the role of computer security in sound management, the importance of performing cost effective computer security, the importance of clearly defining accountability and responsibilities in computer security, emphasizing the role of system owners outside of the organization, emphasizing the employment of an integrated and comprehensive approach, the importance of assessing computer security on a regular basis, and describing the relationship between computer security and societal factors.[8] This document also covers cost considerations, significant concepts, and the correlation between different security controls, eventually offering solutions to ensure that resources are secure.[46]

SP 800-30, Rev. 1

This document mainly concentrates on providing guidance for the development of information systems risk assessment. Risk assessment plans are conducted using NIST SP 800-30 based on the recommendations and principles of the NIST methodology. This guidance facilitates the understanding of cyber risks for decision makers in the organization.[46] When decision makers realize the risks and issues mentioned by a technician, they can make smart decisions based on the available resources and budget.[8]

SP 800-37, Rev. 2

This framework mainly concentrates on providing guidelines to apply a risk management framework in information systems and organizations. It also presents guidelines for organizations to implement and manage privacy and security risks regarding the best practices in information systems. The responsibility of managing privacy and security, according to NIST SP 800-37, belongs to the top management team.[8]

SP 800-39

This document mainly concentrates on providing guidance to organizations on developing a program that aims to manage information security risks regarding the organization's mission, operations, reputation, functions, individuals, image, and assets.[46] This structured and flexible approach specifically concentrates on assessing and monitor risks and responding accordingly. Moreover, this guide towards risk is not intended to take the place of other risk-related measures in organizations.[8]

SP 800-53, Rev. 5

This framework mainly concentrates on security and privacy controls for information systems and organizations aiming to secure assets, individuals, and operations from different cyber threats, including human error, hostile attacks, failures in structure, natural disasters, privacy risks, and threats from foreign intelligence entities.[8] The framework is extensive, and the controls are intentionally made to be "flexible and customizable" in how they help organizations address security and privacy from a functionality perspective.[48]

NIST Cybersecurity Framework

The NIST CSF was established by NIST after the executive order signed by President Obama in 2014. Furthermore, the role of the NIST was updated by the Cybersecurity Enhancement Act of 2014 (CEA), which aimed to cover the identification and development of cybersecurity risk frameworks for critical infrastructure operators and owners. Existing business operations and cybersecurity concerns are covered in this framework. Thus, it can be referred to as a foundation for building a new cybersecurity program or improving an existing program, which can be adopted as the best practices by organizations or private sectors to secure their own critical organization.[49]

The NIST CSF helps organizations improve their cybersecurity measures and provides an integrated organizing structure for different approaches in cybersecurity through collecting best practices, standards, and recommendations. In other words, the CSF is a framework that provides a means of expressing cybersecurity requirements while also effectively pointing out the existing gaps in the cybersecurity practices of an organization.

NIST Privacy Framework

The NIST Privacy Framework[50] concentrates on addressing the concerns of organizations wishing to detect and respond to concerns related to privacy and establish innovative services and products while at the same time considering individuals' privacy.[8] This framework is based on five major functions, including identifying, governing, controlling, communicating, and protecting. This framework can also help managers to address privacy concerns in IoT-based environments.

NIST Risk Management Framework

This framework proposes a seven-step process to cybersecurity risk management, including preparing, categorizing, selecting, implementing, assessing, authorizing, and monitoring in order for the organization to manage its privacy and information security risks.[8] This process is designed to be a comprehensive and measurable process that is repeatable at different times. This framework can also be employed in IoT-based environments to address growing privacy and security challenges.

COBIT

As organizations have become more reliant on technology and communication, the likelihood of being impacted by cyber threats from internal and external sources has increased dramatically.[8] Hence, organizations need to follow a consistent approach to ensure that they appropriately identify risks and accurately assess and manage cybersecurity risks. This approach is essential for all organizations, regardless of their size, nature, and sophistication in cybersecurity. With this intent, COBIT was developed by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA), which is an organization founded in 1967 in the United States in response to the growing concerns of computer systems. COBIT was initially released in 1996 to help users and decision-makers of IT systems develop and improve upon an authoritative series of information technology control objectives that are generally accepted. Therefore, they can realize the level of required security and control to protect the assets of their companies through the establishment of an information technology governance model.[51]

In actuality, COBIT is a high-level information technology standard in a governance and management framework that concentrates on broad concepts of decision-making processes in IT management, instead of focusing on the fine details.[16] COBIT includes 34 main IT processes and encompasses the best practices and approaches regarding process, infrastructure, resource, responsibility, and control management within an organization. Each IT process in COBIT includes a series of 318 high-level detailed control objectives (DCOs), as well as a range of control objectives (COs), which are classified into four main categories: planning, implementing, supporting, and monitoring and evaluating.[52]

COBIT is the best choice to be implemented as an integrated solution because of its broadness. However, COBIT is not the best solution in cases where the appropriate implementation of security controls is the first priority, since it does not provide guidelines to achieve predefined control objectives.[53]

Research methodology

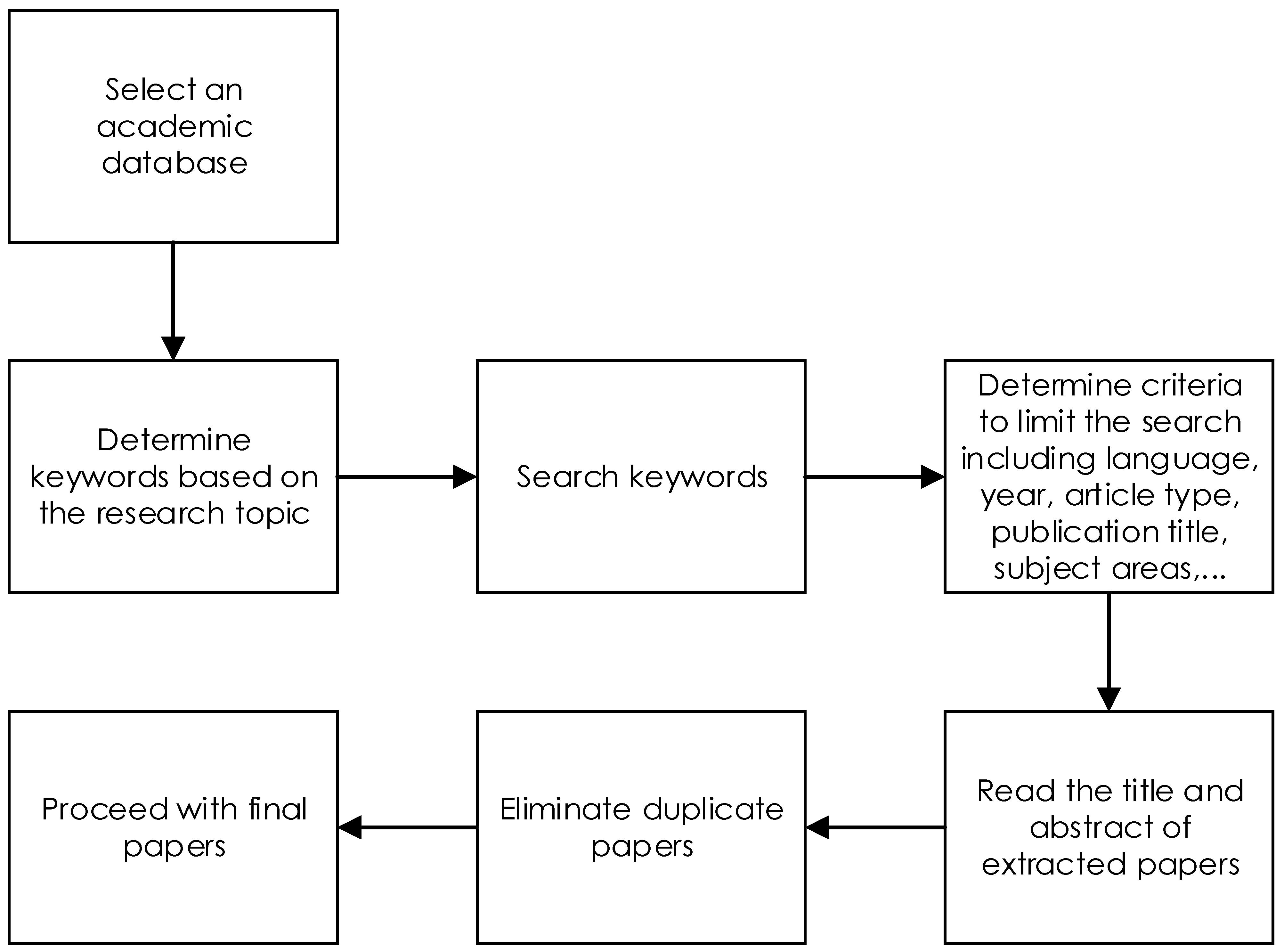

In this section, the employed process to conduct a literature review in this study is described in detail. The objective of the narrative literature review is to respond to the research questions, including how information security standards are being used in different fields and the current condition of the most frequently used information security standards.

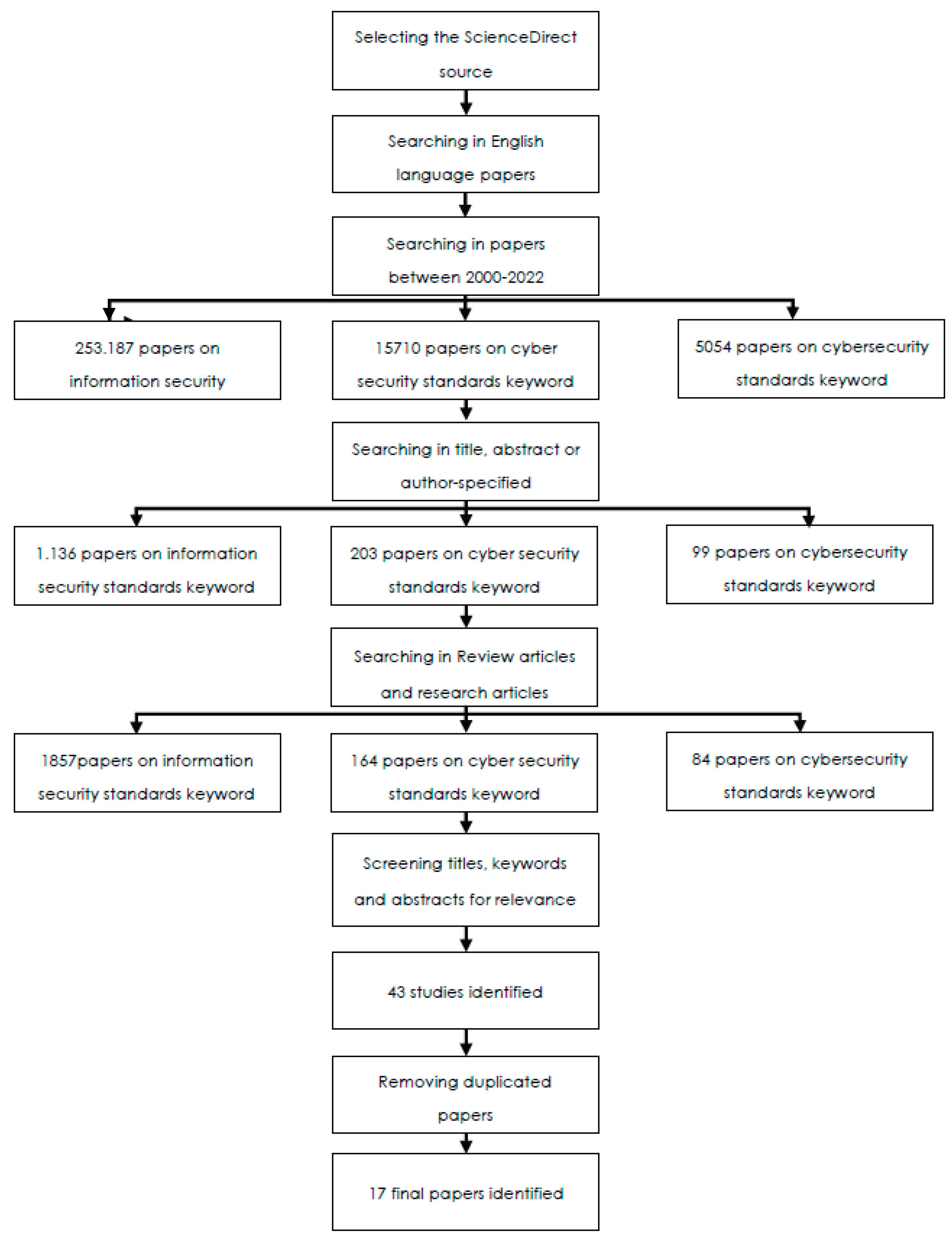

The screening for paper selection was conducted in a process that included several steps. In the first step, a collection of papers based on the literature relevant to information security standards was extracted from the Science Direct database using “information security standards,” “cyber security standards,” and “cybersecurity standards” as keywords in several steps. Limiting the search to the English language and studies that were published from 2000 to 2022 indicated that 253,187 papers were matched to "information security standards," 15,710 papers were matched to "cyber security standards," and 5,054 were matched to "cybersecurity standards."

To analyze the literature review in more depth and limit the number of articles, a query of title, abstract, or author-specified keywords was applied to manually re-screen the search results. The results indicated that there were 1,136 publications on "information security standards," 203 publications on "cyber security standards," and 99 publications on "cybersecurity standards." In the next step, the search result was limited to considering review articles and research articles. Therefore, book chapters, book reviews, discussions, editorials, mini reviews, news reports, short communications, and others were excluded from the search to narrow the search. As a result, 857 publications were found using the "information security standards" keyword, 164 results were found using the "cyber security standards" keyword, and 84 results were found using the "cybersecurity standards" keyword.

The titles, keywords, and abstracts of all extracted papers were scanned and analyzed in terms of relevance to the topic of the research and response to research questions based on their main focus area. As such, studies with no focus on the research topic were excluded from the review. If the title or abstract of a study revealed relevance to the domain of this study, it was included for further examination; otherwise, it was eliminated. Then, extracted papers were narrowed to 43 studies based on the title, abstract, and keywords. In the next step, duplicate papers were found and eliminated from the final list. In cases where the abstract of the study was unclear, the study was carried into the next stage to examine the full content of the study. Through this detailed refining process, 17 studies that met all the criteria were retrieved. The papers that met the criteria to be used as the basis of this narrative literature review are summarized in Table 2, found in the next section.

Figure 4 shows the decision process of selecting the final papers for a narrative literature review.

|

Figure 5 shows the details of the process to select the final papers that were reviewed in this study.

|

Review of information security standards journal articles

Table 2 summarizes the data of 17 extracted articles. For each paper, the title of the paper, author, and publication year are inserted in separate columns. Moreover, the aim of the research, main findings of the research, relevant industry or field of usage, and employed standards were listed to provide an overview of the existing literature. The number of Science Direct citations as of July 29, 2022 are also inserted in a separate column to clarify how each paper is referenced.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Analysis and discussion

Cybersecurity standards and frameworks are significant for consideration in different organizations since they help businesses to identify best practices and methods for use to be equipped against cyber threats and the loss of valuable data.[69][70] These standards provide businesses with consistent metrics-based measures to ensure the effectiveness of methods and procedures that are employed to prevent and mitigate cyber threats.[71]

As noted in this study, there are plenty of cybersecurity standards to be employed that are different in scope and features. In this study, an overview of the most frequently used cybersecurity standards based on existing papers in the cybersecurity field, as well as their features and application areas, has been developed. Additional, a narrative literature review was conducted by extracting 17 relevant papers that were published from 2000 to 2022 regarding cybersecurity standards, while also considering the aim of each research, its main findings, relevant industry, and employed standards. Based on the review of these 17 papers in this study, several key contributions in information security standards have been identified.

Breda and Kiss[54] introduced MIL-STD-285 and IEEE 299-2006 as two appropriate standards to implement in electromagnetic shielding emission security in manufacturing, based on the design of protected areas, and by investigating the appropriate standard to provide protective measures. However, among 17 reviewed papers, these two standards were the main focus of just one article.

Referring to the findings of Siponen and Willison[67] and their comparison of the validation and application of cybersecurity standards, BS7799, GASPP/GAISP, ISO/IEC 17799:2000, and SSE-CMM are standards that are universal and generally can be employed in organizations of different sizes and natures.

According to Humphreys[59]—who analyzed ISO/IEC 27001 in terms of following the management PDCA cycle and controls in response to insider threats in organizations of different sizes and natures—training personnel regarding security, handling critical information, managing access controls, declaring the separation of duties, performing regular backups, engaging in social engineering, and addressing mobile devices are recognized as major controls in ISO/IEC 27001 to deal with insider threats. Theoharidou et al.[68] also demonstrated the effectiveness of ISO/IEC 17799 in addressing insider threats.

Moreover, Hemphill and Longstreet[58] have focused on data breaches in the U.S. retail economy, considering in particular the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS). PCI DSS is a standard in cybersecurity that is employed in the finance and banking industry for credit cards, debit cards, and pre-paid cards that are issued by Discover, American Express, MasterCard, Visa, and JCB International, among others. This standard is not compulsory to be implemented in the U.S.; however, the combination of self-regulation and market forces in industries that use cards significantly motivates the response to cyber threats.

Security management guidelines and network security guidelines, including ISO/IEC 17799, ISO/IEC 18028, ISO/IEC 24743, ISO/IEC TR 13335-5, and ISO/IEC TR 15947 are reviewed by Fumy[29], who concluded that the role of human awareness to combat cyber threats is the most significant issue to be considered.

Moreover, Srinivas et al.[28] analyze cyberattacks—along with security requirements and measures—and discussed CIMF, which is the architecture of the cybersecurity incident management framework. The authors also introduce the main purpose of CIMF: to develop an integrated management mechanism to respond to cyber threats and incidents.

Rowlingson and Winsborrow[66] compared PCI DSS and ISO/IEC 17799, concluding that although both standards have a lot in common in terms of aim and objectives, they differ significantly in terms of scope. ISO/IEC 17799 is a general standard that can be employed in a wide range of organizations; however, PCI DSS is applicable for a limited range of information systems, and its implication costs depend on the maturity of the systems and the security processes and controls within a system.

In studies that have been developed regarding security in micro grids[65], an overview of cybersecurity standards that may be found useful in this regard has been developed. However, in all these studies, it was concluded that there is no significant standard to guarantee the security of a smart grid, and a combination of standards[61]—or the one that is the best match based on the case—should be employed.[62]

Broderick[55] analyzed security standards and regulations, and BS 7799-2, ISO/IEC 17799, ISO/IEC 27001, and COBIT were recognized as the most popular information security frameworks and standards that are oriented toward each other. Moreover, the ISO/IEC 17799:2005 standard does not include any guide to implement network isolation except for auditing network physical isolation. Additionally, Lai and Dai[60] suggested the provision of a technique viewpoint and a management viewpoint for network isolation purposes.

From the review, it was also concluded that despite the fact that ISO 27500 and ISO 31000 complete each other[56], they do not make explicit reference to each other. Thus, ISO 27500 is just a framework that does not specify any certain method or control.

To evaluate the performance of standards in mobile and wireless communication, Papapanagiotou et al.[63] developed a prototype implementation to compare ADOPT, CPC-OCSP, CRLs, CSI, and SCVP standards and relevant resulting parameters, concluding that CPC-OCSP-based schemes perform better in comparison to other standards in the information and communication technology (ICT) industry. Considering security breaches as the result of inadequately employing IoT devices in smart homes, Piasecki et al.[64] concentrated on DCMS and ENISA standards as applicable standards for smart homes.

Limitations of this review

The scope of the study is limited, since it only refers to the Science Direct database for the extraction of papers. Searching other databases may lead to a broader range of articles and expand the discussion, providing additional literature. Moreover, the search is limited to papers that were published between 2000 and 2022. Thus, articles that are published before 2000 are out of the scope of the study.

Conclusions

This work presented the various types of cybersecurity and information security standards and frameworks and their applications in different fields to ensure the security of data against cyber threats. Based on their nature, some standards are considered mandatory for organizations to follow in order to become certified; however, some standards, such as ISO/IEC 17799, are applicable to all types of organizations, regardless of their size and type. Moreover, in some cases, the application of one standard may not fulfill all the demands of an organization, and it may be necessary to employ a combination of standards in order to ensure security against cyber threats and data loss.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- ↑ Vaidya, R. (3 April 2019). "Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2019". GOV.UK. Government Digital Service. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/cyber-security-breaches-survey-2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Syafrizal, Melwin; Selamat, Siti Rahayu; Zakaria, Nurul Azma (16 April 2022). "Analysis of Cybersecurity Standard and Framework Components". International Journal of Communication Networks and Information Security (IJCNIS) 12 (3). doi:10.17762/ijcnis.v12i3.4817. ISSN 2073-607X. https://www.ijcnis.org/index.php/ijcnis/article/view/4817.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 European Commission; Joint Research Centre (2019). Making the rules: the governance of standard development organizations and their policies on intellectual property rights.. LU: Publications Office. doi:10.2760/48536. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/48536.

- ↑ Taherdoost, H.; Sahibudin, S.; Jalaliyoon, N. (2011). "Smart Card Security; Technology and Adoption". International Journal of Security 5 (2): 47–84. https://www.cscjournals.org/library/manuscriptinfo.php?mc=IJS-84.

- ↑ "What is a standard?". Standards Australia. 2022. https://www.standards.org.au/standards-development/what-is-standard. Retrieved 01 February 2022.

- ↑ "ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2: Rules for the structure and drafting of International Standards" (PDF). International Organization for Standardization, International Electrotechnical Commission. 2011. https://boss.cen.eu/media/yypjl3mn/iso_iec_directives_part2.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Collier, Zachary A.; DiMase, Daniel; Walters, Steve; Tehranipoor, Mark Mohammad; Lambert, James H.; Linkov, Igor (1 September 2014). "Cybersecurity Standards: Managing Risk and Creating Resilience". Computer 47 (9): 70–76. doi:10.1109/MC.2013.448. ISSN 0018-9162. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6701301/.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 Karie, Nickson M.; Sahri, Nor Masri; Yang, Wencheng; Valli, Craig; Kebande, Victor R. (2021). "A Review of Security Standards and Frameworks for IoT-Based Smart Environments". IEEE Access 9: 121975–121995. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3109886. ISSN 2169-3536. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9528421/.

- ↑ Knapp, K.J.; Maurer, C.; Plachkinova, M. (2017). "Maintaining a Cybersecurity Curriculum: Professional Certifications as Valuable Guidance". Journal of Information Systems Education 28 (2): 101–14. http://jise.org/Volume28/n2/JISEv28n2p101.html.

- ↑ Purser, Steve (2014). "Standards for Cyber Security". Best Practices in Computer Network Defense: Incident Detection and Response: 97–106. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-372-8-97. https://ebooks.iospress.nl/doi/10.3233/978-1-61499-372-8-97.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Tofan, D.C. (2011). "Information Security Standards". Journal of Mobile, Embedded and Distributed Systems 3 (3): 128–35. http://www.jmeds.eu/index.php/jmeds/article/view/Information-Security-Standards.

- ↑ Maleh, Y.; Sahid, A.; Alazab, M.; Belaissaoui, M. (2021). IT Governance and Information Security: Guides, Standards, and Frameworks (1st ed.). CRC Press. pp. 340. ISBN 9780367753245. https://www.routledge.com/IT-Governance-and-Information-Security-Guides-Standards-and-Frameworks/Maleh-Sahid-Alazab-Belaissaoui/p/book/9780367753245.

- ↑ Taherdoost, Hamed (13 November 2017). "Understanding of e-service security dimensions and its effect on quality and intention to use" (in en). Information & Computer Security 25 (5): 535–559. doi:10.1108/ICS-09-2016-0074. ISSN 2056-4961. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ICS-09-2016-0074/full/html.

- ↑ Kaur, Jagpreet; Ramkumar, K .R. (1 September 2022). "The recent trends in cyber security: A review" (in en). Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 34 (8): 5766–5781. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2021.01.018. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1319157821000203.

- ↑ Dong, Siyuan; Cao, Jun; Flynn, David; Fan, Zhong (1 December 2022). "Cybersecurity in smart local energy systems: requirements, challenges, and standards" (in en). Energy Informatics 5 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s42162-022-00195-7. ISSN 2520-8942. https://energyinformatics.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42162-022-00195-7.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Arora, V. (2010). "Comparing different information security standards: COBIT v s. ISO 27001" (PDF). Carnegie Mellon University, Qatar. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160113101309/http://qatar.cmu.edu/media/assets/CPUCIS2010-1.pdf.

- ↑ Krechmer, K. (2005). "The Meaning of Open Standards". Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Big Island, HI, USA: IEEE): 204b–204b. doi:10.1109/HICSS.2005.605. ISBN 978-0-7695-2268-5. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1385656/.

- ↑ Heckman, James J.; Heinrich, Carolyn; Smith, Jeffrey (23/2002). "The Performance of Performance Standards". The Journal of Human Resources 37 (4): 778. doi:10.2307/3069617. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3069617?origin=crossref.

- ↑ Bloor, Michael; Sampson, Helen (1 December 2009). "Regulatory enforcement of labour standards in an outsourcing globalized industry: the case of the shipping industry" (in en). Work, Employment and Society 23 (4): 711–726. doi:10.1177/0950017009344915. ISSN 0950-0170. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0950017009344915.

- ↑ Dedeke, Adenekan; Masterson, Katherine (8 July 2019). "Contrasting cybersecurity implementation frameworks (CIF) from three countries" (in en). Information & Computer Security 27 (3): 373–392. doi:10.1108/ICS-10-2018-0122. ISSN 2056-4961. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ICS-10-2018-0122/full/html.

- ↑ Taherdoost, Hamed; Masrom, Maslin (1 June 2009). "An examination of smart card technology acceptance using adoption model". Proceedings of the ITI 2009 31st International Conference on Information Technology Interfaces: 329–334. doi:10.1109/ITI.2009.5196103. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5196103/.

- ↑ Seeburn, K. (2014). Basic Foundational Concepts Student Book: Using COBIT® 5. ISACA. https://www.scribd.com/document/347796352/COBIT5-Student-Book.

- ↑ Antunes, Mário; Maximiano, Marisa; Gomes, Ricardo; Pinto, Daniel (8 April 2021). "Information Security and Cybersecurity Management: A Case Study with SMEs in Portugal" (in en). Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 1 (2): 219–238. doi:10.3390/jcp1020012. ISSN 2624-800X. https://www.mdpi.com/2624-800X/1/2/12.

- ↑ Yigit Ozkan, Bilge; van Lingen, Sonny; Spruit, Marco (13 February 2021). "The Cybersecurity Focus Area Maturity (CYSFAM) Model" (in en). Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 1 (1): 119–139. doi:10.3390/jcp1010007. ISSN 2624-800X. https://www.mdpi.com/2624-800X/1/1/7.

- ↑ Donaldson, Scott E.; Siegel, Stanley G.; Williams, Chris K.; Aslam, Abdul (2015). Enterprise cybersecurity: how to build a successful cyberdefense program against advanced threats. The expert's voice in cybersecurity. New York, NY: Apress. ISBN 978-1-4302-6082-0.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Azmi, Riza; Tibben, William; Win, Khin Than (4 May 2018). "Review of cybersecurity frameworks: context and shared concepts" (in en). Journal of Cyber Policy 3 (2): 258–283. doi:10.1080/23738871.2018.1520271. ISSN 2373-8871. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23738871.2018.1520271.

- ↑ Shackelford, S.J.; Russell, S.; Haut, J. (2016). "Bottoms Up: A Comparison of Voluntary Cybersecurity Frameworks". UC Davis Business Law Journal 16 (2): 217–60. https://blj.ucdavis.edu/archives/vol-16-no-2/bottoms-up.html.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Srinivas, Jangirala; Das, Ashok Kumar; Kumar, Neeraj (1 March 2019). "Government regulations in cyber security: Framework, standards and recommendations" (in en). Future Generation Computer Systems 92: 178–188. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.09.063. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167739X18316753.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Fumy, Walter (1 December 2004). "IT security standardisation" (in en). Network Security 2004 (12): 6–11. doi:10.1016/S1353-4858(04)00169-2. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1353485804001692.

- ↑ Koza, E. (2022). "Semantic Analysis of ISO/IEC 27000 Standard Series and NIST Cybersecurity Framework to Outline Differences and Consistencies in the Context of Operational and Strategic Information Security". Medicon Engineering Themes 2 (3): 26–39. https://themedicon.com/pdf/engineeringthemes/MCET-02-021.pdf.

- ↑ Viguri Cordero, Jorge Agustín (23 July 2021). "Las normas ISO/IEC como mecanismos de responsabilidad proactiva en el Reglamento General de Protección de Datos" (in es). IDP. Revista de Internet Derecho y Política (33). doi:10.7238/idp.v0i33.376366. https://raco.cat/index.php/IDP/article/view/n33-viguri/483252.

- ↑ Fonseca-Herrera, O.A.; Rojas, A.E.; Florez, H. (2021). "A Model of an Information Security Management System Based on NTC-ISO/IEC 27001 Standard". IAENG International Journal of Computer Science 48 (2): 213–22. https://www.iaeng.org/IJCS/issues_v48/issue_2/.

- ↑ Rumiche, R.E. (2021). "Implementación de un plan de seguridad informática basado en la norma ISO IEC/27002, para optimizar la gestión en la Corte Superior de Justicia de Lima". Universidad Privada del Norte. https://hdl.handle.net/11537/29848.

- ↑ Meilita Karenda Putri; Hakim, Arif Rahman (17 November 2021). "Perancangan Manajemen Risiko Keamanan Informasi Layanan Jaringan MKP Berdasarkan Kerangka Kerja ISO/IEC 27005:2018 dan NIST SP 800-30 Revisi 1". Info Kripto 15 (3): 134–141. doi:10.56706/ik.v15i3.34. ISSN 1978-7723. https://infokripto.poltekssn.ac.id/index.php/infokripto/article/view/34.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Schmitz, Christopher; Schmid, Michael; Harborth, David; Pape, Sebastian (1 September 2021). "Maturity level assessments of information security controls: An empirical analysis of practitioners assessment capabilities" (in en). Computers & Security 108: 102306. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102306. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167404821001309.

- ↑ "BSI-Standard 200-1: Information Security Management Systems (ISMS)". Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik. 7 May 2018. https://www.bsi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/BSI/Grundschutz/International/bsi-standard-2001_en_pdf.html?nn=908032.

- ↑ "BSI-Standard 200-2: IT-Grundschutz-Methodology". Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik. 7 May 2018. https://www.bsi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/BSI/Grundschutz/International/bsi-standard-2002_en_pdf.html?nn=908032.

- ↑ "BSI-Standard 200-3: Risk Analysis based on IT-Grundschutz". Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik. 7 May 2018. https://www.bsi.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/BSI/Grundschutz/International/bsi-standard-2003_en_pdf.html?nn=908032.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Leander, Björn; Čaušević, Aida; Hansson, Hans (26 August 2019). "Applicability of the IEC 62443 standard in Industry 4.0 / IIoT" (in en). Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (Canterbury CA United Kingdom: ACM): 1–8. doi:10.1145/3339252.3341481. ISBN 978-1-4503-7164-3. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3339252.3341481.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Macher, Georg; Schmittner, Christoph; Veledar, Omar; Brenner, Eugen (2020), Casimiro, António; Ortmeier, Frank; Schoitsch, Erwin et al.., eds., "ISO/SAE DIS 21434 Automotive Cybersecurity Standard - In a Nutshell" (in en), Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security. SAFECOMP 2020 Workshops (Cham: Springer International Publishing) 12235: 123–135, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-55583-2_9, ISBN 978-3-030-55582-5, https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-55583-2_9. Retrieved 2023-03-15

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Choo, Kim-Kwang Raymond; Gai, Keke; Chiaraviglio, Luca; Yang, Qing (1 March 2021). "A multidisciplinary approach to Internet of Things (IoT) cybersecurity and risk management" (in en). Computers & Security 102: 102136. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2020.102136. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167404820304090.

- ↑ Boboň, S. (June 2021). "Analysis of NIST FIPS 140-2 security certificates" (PDF). Masaryk University. https://is.muni.cz/th/wftuc/thesis_Archive.pdf.

- ↑ "FIPS PUB 140-3 Security Requirement for Cyptographic Modules" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. 22 March 2019. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/FIPS/NIST.FIPS.140-3.pdf.

- ↑ Saarinen, Markku-Juhani O. (1 June 2022). "SP 800–22 and GM/T 0005–2012 Tests: Clearly Obsolete, Possibly Harmful". 2022 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW) (Genoa, Italy: IEEE): 31–37. doi:10.1109/EuroSPW55150.2022.00011. ISBN 978-1-6654-9560-8. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9799325/.

- ↑ "NIST Special Publication". Computer Security Resource Center Glossary. 2022. https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/nist_special_publication.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Almuhammadi, Sultan; Alsaleh, Majeed (25 February 2017). "Information Security Maturity Model for Nist Cyber Security Framework". Computer Science & Information Technology (CS & IT) (Academy & Industry Research Collaboration Center (AIRCC)) 7: 51–62. doi:10.5121/csit.2017.70305. ISBN 978-1-921987-62-5. http://airccj.org/CSCP/vol7/csit76505.pdf.

- ↑ "Analysis and Comparison of the NIST SP 800-53 and ISO/IEC 27001:2013". Proceedings of the Workshop on Cybersecurity Providing in Information and Telecommunication Systems. CEUR Workshop Proceedings 3288: 21–32. 2022. ISSN 1613-0073. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3288/.

- ↑ "SP 800-53 Rev. 5 Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations". National Institute of Standards and Technology. 23 September 2020. https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-53/rev-5/final.

- ↑ Barrett, M.P. (16 April 2018). "Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1". NIST Cybersecurity Framework (Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology). doi:10.6028/nist.cswp.04162018. http://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.04162018.pdf.

- ↑ Boeckl, K.R.; Lefkovitz, N.B. (16 January 2020). NIST Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy Through Enterprise Risk Management, Version 1.0. Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology. doi:10.6028/nist.cswp.01162020. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.01162020.pdf.

- ↑ The IT Governance Institute (2005). "Aligning COBIT, ITIL and ISO 17799 for Business Benefit: Management Summary" (PDF). IT Governance Institute. https://www.itgovernance.co.uk/files/itil-cobit-iso17799jointframework.pdf.

- ↑ Amorim, Ana Cláudia; Mira da Silva, Miguel; Pereira, Rúben; Gonçalves, Margarida (1 November 2021). "Using agile methodologies for adopting COBIT" (in en). Information Systems 101: 101496. doi:10.1016/j.is.2020.101496. ISSN 0306-4379. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306437920300077.

- ↑ Kozina, M. (2021). "IT Risk Management in the enterprise using CobiT 5". Proceedings of CECIIS 2021. https://submissions.foi.hr/index.php/ceciis/article/view/25.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Breda, Gabor; Kiss, Miklos (2020). "Overview of Information Security Standards in the Field of Special Protected Industry 4.0 Areas & Industrial Security" (in en). Procedia Manufacturing 46: 580–590. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2020.03.084. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2351978920309628.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Broderick, J. Stuart (2006). "ISMS, security standards and security regulations" (in en). Information Security Technical Report 11 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1016/j.istr.2005.12.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1363412705000750.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Everett, Cath (1 February 2011). "A risky business: ISO 31000 and 27005 unwrapped" (in en). Computer Fraud & Security 2011 (2): 5–7. doi:10.1016/S1361-3723(11)70015-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S136137231170015X.

- ↑ Gil-García, J. Ramón (1 January 2004). "Information technology policies and standards: A comparative review of the states" (in en). Journal of Government Information 30 (5-6): 548–560. doi:10.1016/j.jgi.2004.10.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1352023704000681.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Hemphill, Thomas A.; Longstreet, Phil (1 February 2016). "Financial data breaches in the U.S. retail economy: Restoring confidence in information technology security standards" (in en). Technology in Society 44: 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2015.11.007. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0160791X15300154.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Humphreys, Edward (1 November 2008). "Information security management standards: Compliance, governance and risk management" (in en). Information Security Technical Report 13 (4): 247–255. doi:10.1016/j.istr.2008.10.010. ISSN 1363-4127. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1363412708000514.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Lai, Yeu-Pong; Dai, Ruan-Han (1 June 2009). "The implementation guidance for practicing network isolation by referring to ISO-17799 standard" (in en). Computer Standards & Interfaces 31 (4): 748–756. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2008.09.008. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920548908001128.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Leszczyna, Rafał (1 February 2018). "Cybersecurity and privacy in standards for smart grids – A comprehensive survey" (in en). Computer Standards & Interfaces 56: 62–73. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2017.09.005. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920548917301277.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Leszczyna, Rafał (1 September 2018). "Standards on cyber security assessment of smart grid" (in en). International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection 22: 70–89. doi:10.1016/j.ijcip.2018.05.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1874548216301421.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Papapanagiotou, K.; Marias, G.F.; Georgiadis, P. (1 October 2010). "Revising centralized certificate validation standards for mobile and wireless communications" (in en). Computer Standards & Interfaces 32 (5-6): 281–287. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2009.07.001. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920548909000592.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Piasecki, Stanislaw; Urquhart, Lachlan; McAuley, Professor Derek (1 September 2021). "Defence against the dark artefacts: Smart home cybercrimes and cybersecurity standards" (in en). Computer Law & Security Review 42: 105542. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2021.105542. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0267364921000157.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Priyadharshini, N.; Gomathy, S.; Sabarimuthu, M. (1 December 2020). "WITHDRAWN: A review on microgrid architecture, cyber security threats and standards" (in en). Materials Today: Proceedings: S2214785320382456. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.622. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214785320382456.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Rowlingson, Robert; Winsborrow, Richard (1 March 2006). "A comparison of the Payment Card Industry data security standard with ISO17799" (in en). Computer Fraud & Security 2006 (3): 16–19. doi:10.1016/S1361-3723(06)70323-2. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1361372306703232.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Siponen, Mikko; Willison, Robert (1 June 2009). "Information security management standards: Problems and solutions" (in en). Information & Management 46 (5): 267–270. doi:10.1016/j.im.2008.12.007. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378720609000561.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Theoharidou, Marianthi; Kokolakis, Spyros; Karyda, Maria; Kiountouzis, Evangelos (1 September 2005). "The insider threat to information systems and the effectiveness of ISO17799" (in en). Computers & Security 24 (6): 472–484. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2005.05.002. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167404805000684.

- ↑ Taherdoost, Hamed; Sahibuddin, Shamsul; Jalaliyoon, Neda (2015). "A Review Paper on e-service; Technology Concepts" (in en). Procedia Technology 19: 1067–1074. doi:10.1016/j.protcy.2015.02.152. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S221201731500153X.

- ↑ Taherdoost, Hamed; Hassan, Ali (2020), Ho, Ree C., ed., "Development of an E-Service Quality Model (eSQM) to Assess the Quality of E-Service:", Advances in Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, and E-Services (IGI Global): 177–207, doi:10.4018/978-1-5225-9697-4.ch011, ISBN 978-1-5225-9697-4, http://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-5225-9697-4.ch011. Retrieved 2023-03-15

- ↑ Mishra, Shailendra; Alowaidi, Majed A.; Sharma, Sunil Kumar (2 January 2021). "Impact of security standards and policies on the credibility of e-government" (in en). Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing. doi:10.1007/s12652-020-02767-5. ISSN 1868-5137. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s12652-020-02767-5.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, grammar, and punctuation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The BSI standards discussed in the original refer to the old 100 standards, for some unknown reason; they were updated to the 200-X series of standards for this version. Additional references to those 200-X standards are also supplied in this version. Similarly, the author refers to FIPS 140-2 instead of 140-3, for some unknown reason, despite 140-3 being released in March 2019; 140-3 is used in this version, and an additional reference is supplied. The NIST SP 800-X series descriptions were arguably opaque and outdated in the original; additional modifications were made to clarify that content and remove withdrawn items (like NIST SP 800-14) for this version.