Journal:Human–information interaction with complex information for decision-making

| Full article title | Human–information interaction with complex information for decision-making |

|---|---|

| Journal | Informatics |

| Author(s) | Albers, Michael J. |

| Author affiliation(s) | Department of English, East Carolina University |

| Primary contact | E-Mail: albersm@ecu.edu; Tel.: +1-252-328-6374 |

| Editors | Sedig, Kamran; Parsons, Paul |

| Year published | 2015 |

| Volume and issue | 2 (2) |

| Page(s) | 4–19 |

| DOI | 10.3390/informatics2020004 |

| ISSN | 2227-9709 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | http://www.mdpi.com/2227-9709/2/2/4 |

Abstract

Human–information interaction (HII) for simple information and for complex information is different because people's goals and information needs differ between the two cases. With complex information, comprehension comes from understanding the relationships and interactions within the information and factors outside of a design team's control. Yet, a design team must consider all these within an HII design in order to maximize the communication potential. This paper considers how simple and complex information requires different design strategies and how those strategies differ.

Keywords: human–information interaction, decision-making, complex communication, information design

Introduction

A primary goal of human–information interaction (HII) for complex information is to communicate concepts and ideas to be used for decisions. That is, information that a reader uses to develop an understanding of a situation and to make decisions about a complex situation [1–3].

In any complex communication situation, the proper amount of information should result in maximum communication; of course, too little, too much, poor organization, or inappropriate content reduces the communication. Stating that the communication needs to provide the proper amount of information could considered tautological. It is easy to claim — and adds little to a discussion — a text should have the proper information (I use text within the article in a generic sense: paper, web pages, etc). However, defining and measuring the communication value of a document (and the information it contains) proves to be a much more difficult task.

The interaction and presentation needs of complex information are very different from those of simple information, where a person looks for single information elements. For example, consider the difference in looking up the score of yesterday’s game (simple information) and considering house remodeling to help care for a chronically sick parent (complex information). When we move from a communication viewpoint to an HII viewpoint, we also bring into play issues of how a person can manipulate the information [2,4,5]. The base text may contain the “proper information” but for maximum communication, it may need to be reordered or otherwise manipulated to meet individual needs.

A large percentage of the HII literature either looks at simple information search and interaction or conflates simple and complex information. It also tends to take a web-based focus with the person having an essentially infinite number of sources to explore [6]. While this is true in many cases, within this article, I take a much narrower focus on HII and look at the construction of content within a single set of information that is under a content development team’s control, such as the production of corporate reports or public information for a specific goal (an example presented later will be on communicating hurricane information). A view focused on the design team’s task needs to consider what information to create and how people will interact with it. The more commonly discussed view of people searching the Internet (or other sources) for existing information [7] will not be directly considered since a design team has no control over how that search proceeds or what information the person may view.

Explanation of terms

In the introduction, I used the terms simple and complex information. Here I provide a working definition for each.

Simple information

Simple information can be characterized by existing as a single information element. A high percentage of the “look it up on Google” amounts to simple information. For example, a person can look up when a movie was released or a recipe for a carrot cake. Both fit the definition of simple information. Factors that distinguish simple information include:

- Single path. One path can be fully defined that will result in the answer.

- Right/wrong answer. The correctness can be tested and the information declared correct or not correct.

- Complete information. The completeness can be tested and the information declared complete or not complete.

- Closed system. All of the factors that might influence the answer can be defined and accounted for.

Complex information

Complex information exists at the opposite end from simple answers. There is no single “answer”. Addressing complex questions requires using and integrating multiple information elements, which often conflict. People have a complex web of information needs and interactions to fill those needs [8]. For example, analyzing monthly business reports and making decisions about this month’s production, or making health care choices. Factors that distinguish complex information include:

- Multiple paths. There is no single path to an answer. A person can take many different paths and all will work. The effectiveness of the paths may, of course, vary.

- Open-ended. The idea of “complete” is undefined. A person can continue to collect information and refine their understanding with an essentially infinite amount of information. Instead, a person has to pick a stopping point and make a decision.

- Needs cannot be predefined. The information that a person needs cannot be predefined. Of course the major or essential information can be predefined, but the many smaller information elements that can exert a strong influence vary too much between individuals.

- History. The information exists within a continuum and that history influences how it gets interpreted and used.

- Non-linear. The overall situation shows a non-linear response with small differences in some information elements resulting in very large differences in appropriate decisions.

- Open system. All of the factors that might influence the decision cannot be defined. There are too many and the information is dynamic, changing on time scales relevant to the decision situation.

Most of the simple information that gets communicated tends to be single facts or procedural type of information. Complex information, on the other hand, deals with a broader scope.

- Complex information communicates concepts and ideas.

- Complex information communicates an understanding of a situation.

- Complex information communicates relationships and interactions.

Clearly, the HII required to maximize the communication of complex information is very different between the two. Most writing and UX guidelines deal with communicating simple information. But to really address people’s information needs, we need to consider why and how they interact with complex information. Consider the case of electronic health records — they clearly represent complex information — and represent an example where the design team has control over a significant part of how the HII occurs. The design has to consider many potentially conflicting sets of priorities (development time, maintenance cost, hospital administration goals, government regulations, medical needs, etc.), which, in turn, affect how well the users can interact with the information. The input methods must be efficient for data entry, but presenting the information the same way to a nurse or physician may not be the best for integrating it into a clear view of the patient’s condition. The relationships of information (connecting the results of various medical tests, etc.) should reflect the initial diagnosis and should also reflect the changing patient status as treatment progresses.

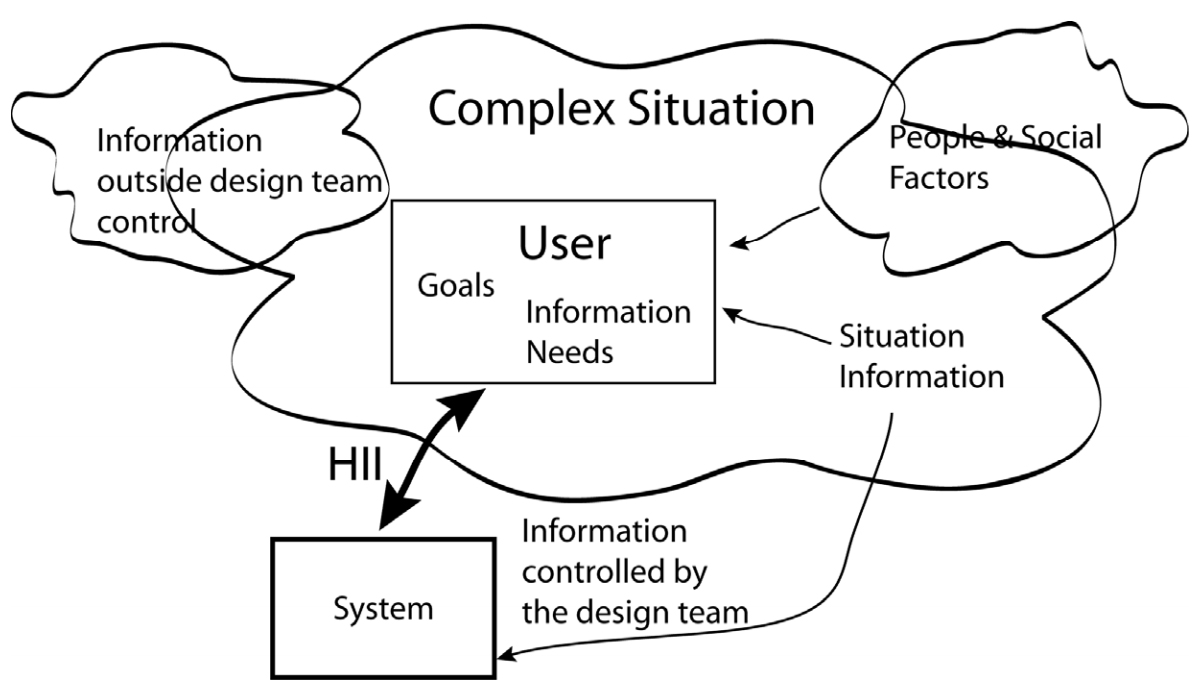

In previous work, I have defined a situation as “the current world state which the user needs to understand. An underlying assumption is that the user needs to interact with a system to gain the necessary information in order to understand the situation” ([1], p. 11). The information relevant to the HII exists both inside and outside any circle drawn to enclose “the situation” (Figure 1). Honestly, the difficulty of drawing that enclosing circle is a characteristic of a complex situation.

Figure 1. Complex situation with information both inside and outside of a design team’s control.

Human–information interaction (HII) only directly applies to the information a design team controls.

Once an upfront analysis has defined the people’s goals and information needs, then the HII factors which support manipulating the information and revealing the relationships can be considered and entered into the design [2,9].

Typically, the failure of these technical documents [used here in a generic sense for any information source] comes not from a lack of information; the text probably contains an excess of information. Post hoc studies of communication failures find many sources to blame: poor information architecture, poor organization, wrong grade level or writing style, or poor presentation. But instead of seeing these problems as a root cause, let’s consider them as symptoms of a more fundamental problem: a problem stemming from the underlying complexity of the situational context and a failure of the information presentation to match that complexity ([10], p. 110).

The task assigned to an HII design team is to ensure the underlying complexity is not overly simplified and that the information presentation and manipulation meets the needs of the people and the demands of the situation. As others have discussed, the HII problem for maximizing the communication for complex information is not a tools question, but one of understanding what people need and how they come to understand the information [11].

Information relationships

Understanding complex information depends on understanding relationships, but the potential relationships are essentially infinite. Comprehension of a complex situation occurs when people can mentally integrate those relationships into their view of the situation.

Information integration lies, not in a text element itself, but in the relationships between those elements. A reader needs to figure out what information is relevant and how to connect it to the current problem. Without proper information relationships, the reader does not gain an integrated understanding of information, but instead gains a collection of facts. Without relationships, information exists as a bunch of interesting factoids which do not help a person form an adequate mental picture of the situation. Collections of facts are less than useful for understanding and working with the open-ended problems that people encounter in complex situations [12,13]. Without the relationships, a person learns about X and Y, but not how X and Y relate to each other or to Z in terms of their current problem or situation [14]. The text fails to communicate because the reader can’t form the necessary information relationships. ([10], p. 111).

A patient trying to understand a medical problem often has difficulty understanding the situation because they don’t understand the relationships. They can look at a set of lab results and know the numbers, but lack the medical practitioner’s knowledge of what the values should be for their condition. The patient may be worried because some values are high, but the physician is satisfied with them because the specific condition often has even higher values. Likewise, a junior manager needs to develop the knowledge of how to interpret multiple values that may appear on a collection of monthly reports. Good HII can help by providing a more integrated view and providing help with the integration, without interfering with more experienced people’s information interaction.

Building relationships means developing a deep-level understanding of the text rather than just a surface-level knowledge. Deep-level knowledge involves seeing the macrostructure of the text and being able to apply prior knowledge to it and fit the text within the reader’s prior knowledge framework. Surface-level knowledge involves knowing the basic text. People with surface-level knowledge can quote the text and if asked recall-type questions would respond with answers very close to the text language, but they would not be able to elaborate on the answer or connect it to other information. People with deep-level understanding would be able to place the text’s information into their own words. A major element in the difference between people being able to develop deep-level understanding versus a surface-level understanding is their prior knowledge.

Communicating complex information for decision-making can be viewed as working to help build relationships within the information [8]. Unfortunately, building relationships is a great theoretical concept, but one that does not lend itself to a direct operational definition. One way to define judging or qualifying relationships can be how they reduce the uncertainty a person has about the situation [15]. This reshapes an HII design team’s goal to one of focusing content creation in terms of what information does the reader need to reduce their uncertainty and, consequently, to build a web of relationships between the information elements.

Contextual awareness

Except for training material, the readers of technical information typically understand the basics but need to know specific information about the current situation (as opposed to the general situation) in order to make decisions. The understanding of a complex situation needed to make informed decisions comes when people can distinguish the information structure, grasp the relationships within it [16–18], and make inferences on the future evolution of the situation.

Building on Endsley’s (1995) [19] situation awareness work, we can call this contextual awareness. Contextual awareness is the understanding of the information within an informational situation which forms the basis for how to interpret new information and how to make decisions for interacting with that situation. With poor contextual awareness, people can know something is occurring or that a particular piece of information exists, but they cannot easily find relevant related information or they have the information but do not understand how it relates to the overall situation. On the other hand, good contextual awareness does not guarantee a person will form the proper intention or make the proper decisions; the error analysis literature is filled with cases where people understood a situation, but still made incorrect choices. Unfortunately for design teams, the concept of relevance itself is highly nuanced and multifaceted [17], creating a complex interplay that must be understood to engineer high quality HII.

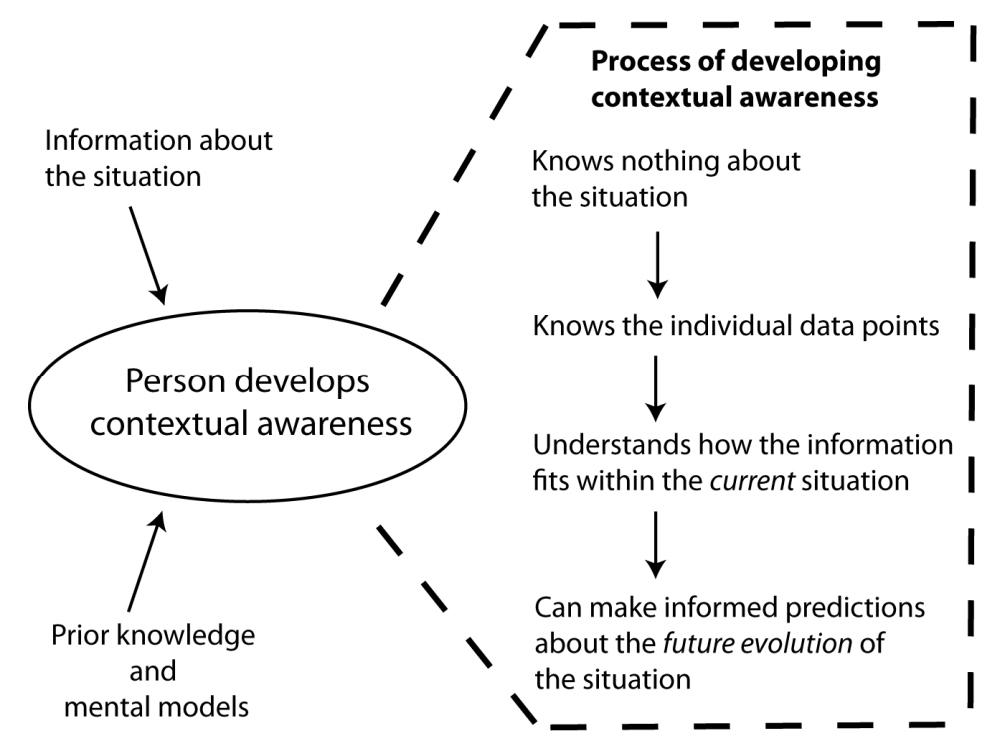

Elements of good contextual awareness are (Figure 2): (1) Understands how the information fits within the current situation. (2) Understands the information relationships [10]. Information comprehension requires knowing how information relates to other information. (3) Understands the future development of the situation and can make predictions about the ripple effects of any decision across the entire situation. HII that supports complex information needs to provide the interactions that support people developing high quality contextual awareness.

Kain, de Jong, and Smith (2010) [21] study into how to communicate hurricane risks and warnings highlighted the issues of how people interpret information and make decisions about how they will react. The hurricane experts had their view of what information was needed and how it should be presented, but the research showed the people wanted/needed a different presentation. Their mental methods of forming relationships and of interpreting complex information differed from what the experts thought. The process of building contextual awareness differs and a design team’s analysis must capture those differences.

A design team working on developing the HII for a country’s hurricane awareness plan needs to balance both the expert’s “here is what the people must hear” against the more pragmatical “here’s what I want to know” as well as the local people’s opinion of how they react to hurricane warnings. Many of them have been through multiple hurricanes and have strongly held views that often conflict with the authorities. Notice how in this case, the design team has control of the information. A general search on hurricane warnings will have sentences such as “consult your local authorities for evacuation routes” but, here, the design team will be tasked with providing that evacuation route information. At the same time, they need to ensure the relationships between evacuation route, getting ready for evacuation, and planning on returning are all clearly laid out and connected.

Figure 2. Stages of developing contextual awareness

HII is information interaction, not data interaction

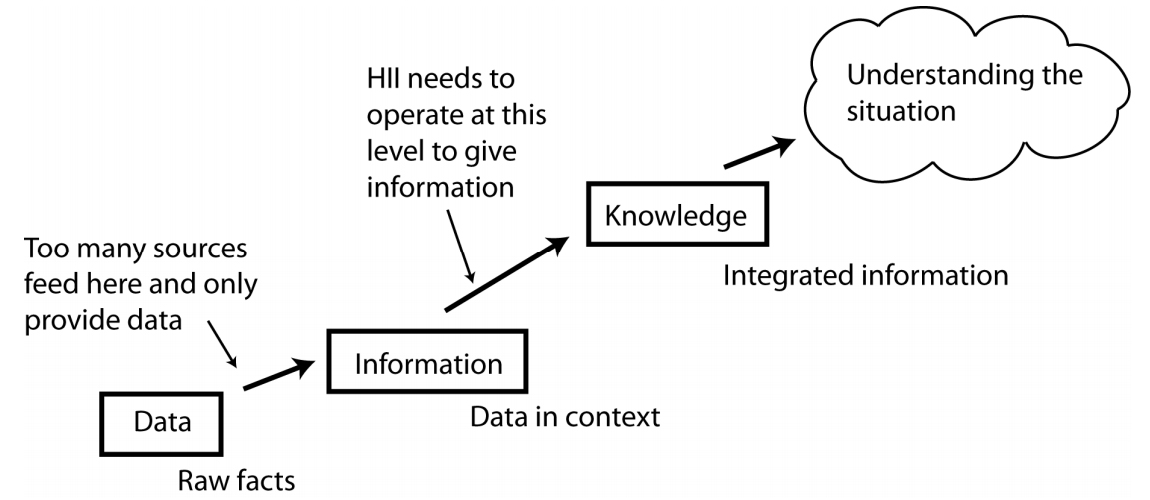

People who are engaged with decision-making and complex information need to be presented with information, not data (Figure 3). Quick definition of my terms here, which I discuss in more detail elsewhere [1].

- Data: Raw numbers, facts, and figures.

- Information: Information is data in context. It relates to the situation and contains the relationships that connect the information to the situation.

- Knowledge: Interconnected web of the relevant information and the relationships linking the information within the situation.

Figure 3. Data, information, and knowledge hierarchy. The higher the HII works in the hierarchy,

the better it fits building an understanding of the situation.

As an example, I heard a presentation that looked at the effect of sea level rise on the Norfolk, VA area [22]. A software program had nice manipulation that let a person dynamically see the effects of different amounts of sea level rise from global warming and how it would affect the city. The problem was not with the implementation, but with the underlying assumptions of a design team. They were assuming that by providing a tool and letting people see how different sea level changes would affect the area that it would bring about understanding and increase long-term preparedness. But the tool was presenting content at the data level. Yes, I can change the sliders and see how the sea level changes, but it was devoid of supporting content (in the metaphor of this paper, the tool was a single puzzle piece). It not only didn’t connect with other pieces, those other pieces were not provided. As a result, a global warming denier could play with the model, agree that a four foot rise would be a catastrophic problem, but then reject it as something that would never happen. One of the software’s goals was to help people prepare, but without giving them the content and relationships to build their contextual awareness; it was a single data point and not part of a coherent presentation of information.

The transition from information to knowledge is important since it involves comprehending the relationships within the data and placing them within the context of the situation. Moving to knowledge is essential to building contextual awareness and must be the goal of an HII design team.