Difference between revisions of "Public health informatics"

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) m (Added image) |

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) (Updated URLs for 2022) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

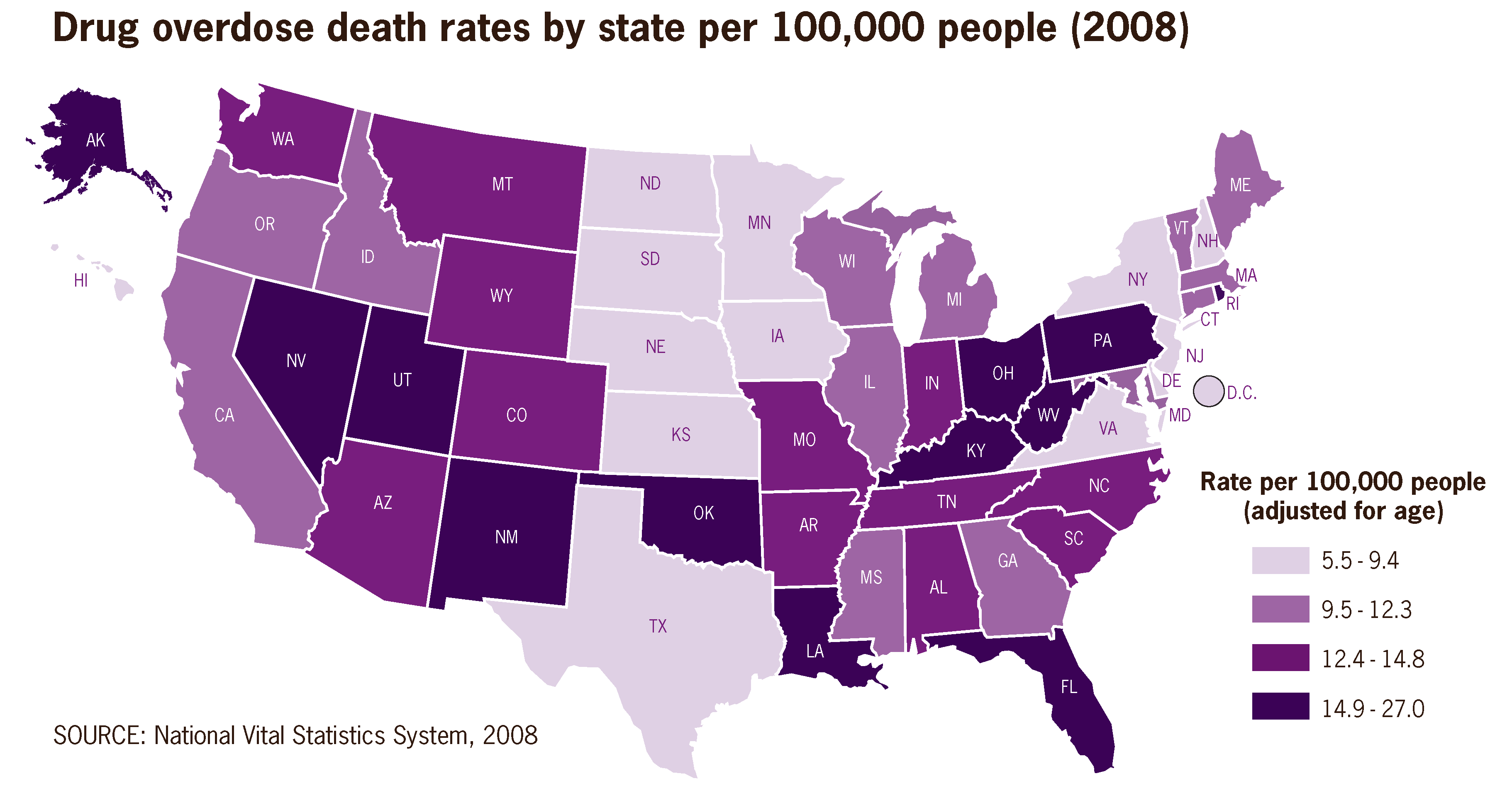

[[Image:Drug overdose death rates by state per 100,000 people 2008 US.png|right|600px|thumbnail|Collecting and utilizing vital statistics data is only one of many applications of public health informatics.]] | [[Image:Drug overdose death rates by state per 100,000 people 2008 US.png|right|600px|thumbnail|Collecting and utilizing vital statistics data is only one of many applications of public health informatics.]] | ||

'''Public health informatics''' has been defined as "the systematic application of [[information]] and computer science and technology to public health practice, research, and learning."<ref name="YasnoffPHI">{{cite journal | '''Public health informatics''' has been defined as "the systematic application of [[information]] and computer science and technology to public health practice, research, and learning."<ref name="YasnoffPHI">{{cite journal |title=Public Health Informatics: Improving and Transforming Public Health in the Information Age |journal=Journal of Public Health Management and Practice |author=Yasnoff, W.A.; O’Carroll, P.W.; Koo, D. et al. |volume=6 |issue=6 |pages=67–75 |year=2000 |doi=10.1097/00124784-200006060-00010 |pmid=18019962}}</ref><ref name="FriedePHI">{{cite journal |title=Public Health Informatics: How Information-Age Technology Can Strengthen Public Health |journal=Annual Review of Public Health |author=Friede, A.; Blum, H.L.; McDonald, M. |volume=16 |pages=239–252 |year=1995 |doi=10.1146/annurev.pu.16.050195.001323 |pmid=7639873}}</ref> Like other types of informatics, public health informatics is a multidisciplinary field, involving the studies of [[Informatics (academic field)|informatics]], computer science, psychology, law, statistics, epidemiology, and microbiology. | ||

In 2000, researcher William A. Yasnoff and his colleagues identified four key aspects that differentiate public health informatics from [[Health informatics|medical informatics]] and other informatics specialty areas. Public health informatics<ref name="YasnoffPHI" />: | In 2000, researcher William A. Yasnoff and his colleagues identified four key aspects that differentiate public health informatics from [[Health informatics|medical informatics]] and other informatics specialty areas. Public health informatics<ref name="YasnoffPHI" />: | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Before the advent of the | Before the advent of the internet, public health data, like other healthcare and business data, were collected on paper forms and stored centrally at the relevant public health agency. As computers became more commonplace, some data and information would be computerized, requiring a distinct data entry process, storage in various file formats, and analysis by mainframe computers using standard batch processing. With the coming of the internet and cheaper large-scale storage technologies, public health agencies with sufficient resources began transitioning to web-accessible collections of public health data, and, more recently, to automated messaging of the same information.<ref name="OCarrollPHI">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ap6uCR0Ybo4C |title=Public Health Informatics and Information Systems |author=O'Carroll, P.W. |publisher=Springer |year=2003 |pages=790 |isbn=9780387954745 |accessdate=21 March 2020}}</ref><ref name="LombardoDS">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-xI2Kl39ZzoC&printsec=frontcover |chapter=Chapter 1: Disease Surveillance, a Public Health Priority |title=Disease Surveillance: A Public Health Informatics Approach |author=Lombardo, J.S.; Buckeridge, D.L. |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2012 |pages=1–40 |isbn=9781118569054 |accessdate=21 March 2020}}</ref><ref name="LeePrincPrac">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FF78GCiUbwUC&pg=PA70 |chapter=Chapter 5: Informatics and the Management of Surveillance Data |title=Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance |author=Krishnamurthy, R.S.; St. Louis, M.E. |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2010 |pages=65–87 |isbn=9780195372922 |accessdate=21 March 2020}}</ref> | ||

==Application== | ==Application== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

Due to the complexity and variability of public health data, like health care data generally, the issue of data modeling presents a particular challenge. Flat data sets for statistical analysis were the norm; however, today's requirements of interoperability and integrated sets of data across the public health enterprise require more sophistication. The relational database is increasingly the norm in public health informatics. Designers and implementers of the many sets of data required for various public health purposes must find a workable balance between very complex and abstract data models and simplistic, ''ad hoc'' models that untrained public health practitioners come up with and feel capable of working with. | Due to the complexity and variability of public health data, like health care data generally, the issue of data modeling presents a particular challenge. Flat data sets for statistical analysis were the norm; however, today's requirements of interoperability and integrated sets of data across the public health enterprise require more sophistication. The relational database is increasingly the norm in public health informatics. Designers and implementers of the many sets of data required for various public health purposes must find a workable balance between very complex and abstract data models and simplistic, ''ad hoc'' models that untrained public health practitioners come up with and feel capable of working with. | ||

Another challenge is found in the need to extract usable public health information from the mass of available heterogeneous data. The public health informaticist is thus required to become familiar with a variety of analysis tools, ranging from business intelligence tools to produce routine or ''ad hoc'' reports, to sophisticated statistical analysis tools and | Another challenge is found in the need to extract usable public health information from the mass of available heterogeneous data. The public health informaticist is thus required to become familiar with a variety of analysis tools, ranging from business intelligence tools to produce routine or ''ad hoc'' reports, to sophisticated statistical analysis tools and [[geographic information system]]s (GIS) to expose the geographical dimension of public health trends. | ||

===In the United States=== | ===In the United States=== | ||

The [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia has played an important role in public health and [[infectious disease informatics]]. The agency's Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services (CSELS; formerly OSELS<ref name="ACDMinsApril13">{{cite web |url= | The [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia has played an important role in public health and [[infectious disease informatics]]. The agency's Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services (CSELS; formerly OSELS<ref name="ACDMinsApril13">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/maso/facm/pdfs/ACDCDC/20130425_CDCACD.pdf |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20190722192037/https://www.cdc.gov/maso/facm/pdfs/ACDCDC/20130425_CDCACD.pdf |format=PDF |title=Advisory Committee to the Director: Record of the April 25, 2013 Meeting |author=Advisory Committee to the Director |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |pages=9–14 |date=July 2013 |archivedate=22 July 2019 |accessdate=06 January 2022}}</ref><ref name="CDCOrgArch">{{cite web |url=http://www.cdc.gov/maso/pdf/CDC_Official.pdf |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130718025323/http://www.cdc.gov/maso/pdf/CDC_Official.pdf |format=PDF |title=Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=27 July 2011 |archivedate=18 July 2013 |accessdate=17 June 2014}}</ref>) and its Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance (DHIS; formerly PHITPO and PHSIPO<ref name="ACDMinsApril13" /><ref name="CDCOrgArch" />) has focused on advancing the state of information science in these realms, applying digital information technologies to aid in the detection and management of diseases and syndromes in individuals and populations.<ref name="DHISAbout">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dhis/documents/dhis-fact-sheet-508.pdf |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20210704090101/https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dhis/documents/dhis-fact-sheet-508.pdf |format=PDF |title=Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance |author=Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=19 June 2018 |archivedate=04 July 2021 |accessdate=06 January 2022}}</ref> The CDC also created the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS)<ref name="DHISAbout" />, which includes a free comprehensive web and message-based reporting system called the NEDSS Base System (NBS), used for managing and transmitting reportable disease data.<ref name="NBSAbout">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/about/nedss.html |title=National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) |author=Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=16 March 2017 |accessdate=06 January 2022}}</ref> | ||

Since 2002, the CDC has promoted the idea of the Public Health Information Network to facilitate the transmission of data from various partners in the health care industry and elsewhere (hospitals, clinical and environmental laboratories, doctors' practices, pharmacies) to local health agencies, then to state health agencies, and then to the CDC. At each stage the entity must be capable of receiving the data, storing it, aggregating it appropriately, and transmitting it to the next level.<ref name="PHIN02">{{cite web |url=http://www.cdc.gov/phin/library/archive_2002/PHIN_Functions_Specifications_121802.pdf |format=PDF |title=Public Health Information Network Functions and Specifications, Version 1.2 |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=18 December 2002 |accessdate= | Since 2002, the CDC has promoted the idea of the Public Health Information Network to facilitate the transmission of data from various partners in the health care industry and elsewhere (hospitals, clinical and environmental laboratories, doctors' practices, pharmacies) to local health agencies, then to state health agencies, and then to the CDC. At each stage the entity must be capable of receiving the data, storing it, aggregating it appropriately, and transmitting it to the next level.<ref name="PHIN02">{{cite web |url=http://www.cdc.gov/phin/library/archive_2002/PHIN_Functions_Specifications_121802.pdf |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111023111340/http://www.cdc.gov/phin/library/archive_2002/PHIN_Functions_Specifications_121802.pdf |format=PDF |title=Public Health Information Network Functions and Specifications, Version 1.2 |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=18 December 2002 |archivedate=23 October 2011 |accessdate=21 March 2020}}</ref> To promote interoperability between the NBS and other informatics systems, the CDC has also encouraged the adoption of several standard vocabularies and messaging formats from the health care world. The most prominent of these are the [[Health Level 7]] (HL7) standards for health care messaging, the LOINC system for encoding laboratory test and result information, and the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) vocabulary of health care concepts.<ref name="NBSAbout" /> | ||

A typical example of data transmissions to the CDC would be infectious disease data, which hospitals, labs, and doctors are legally required to report to local health agencies. The local health agencies must then report to their state public health department and the states must report in aggregate form to the CDC. Among other uses of this received data, the CDC publishes the ''Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report'' (MMWR), "the agency’s primary vehicle for scientific publication of timely, reliable, authoritative, accurate, objective, and useful public health information and recommendations."<ref name="MMWRAbout">{{cite web |url= | A typical example of data transmissions to the CDC would be infectious disease data, which hospitals, labs, and doctors are legally required to report to local health agencies. The local health agencies must then report to their state public health department and the states must report in aggregate form to the CDC. Among other uses of this received data, the CDC publishes the ''Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report'' (MMWR), "the agency’s primary vehicle for scientific publication of timely, reliable, authoritative, accurate, objective, and useful public health information and recommendations."<ref name="MMWRAbout">{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/about.html |title=About the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Series |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=04 March 2020 |accessdate=21 March 2020}}</ref> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Some elements of this article are reused from [ | Some elements of this article are reused from [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health_informatics the Wikipedia article]. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{Reflist|3}} | |||

<!---Place all category tags here--> | <!---Place all category tags here--> | ||

[[Category:Informatics]] | [[Category:Informatics]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:58, 6 January 2022

Public health informatics has been defined as "the systematic application of information and computer science and technology to public health practice, research, and learning."[1][2] Like other types of informatics, public health informatics is a multidisciplinary field, involving the studies of informatics, computer science, psychology, law, statistics, epidemiology, and microbiology.

In 2000, researcher William A. Yasnoff and his colleagues identified four key aspects that differentiate public health informatics from medical informatics and other informatics specialty areas. Public health informatics[1]:

- focuses on "applications of information science and technology that promote the health of populations as opposed to the health of specific individuals."

- focuses on "applications of information science and technology that prevent disease and injury by altering the conditions or the environment that put populations of individuals at risk."

- "explore[s] the potential for prevention at all vulnerable points in the causal chains leading to disease, injury, or disability; applications should not be restricted to particular social, behavioral, or environmental contexts."

- "reflect[s] the governmental context in which public health is practiced."

History

Before the advent of the internet, public health data, like other healthcare and business data, were collected on paper forms and stored centrally at the relevant public health agency. As computers became more commonplace, some data and information would be computerized, requiring a distinct data entry process, storage in various file formats, and analysis by mainframe computers using standard batch processing. With the coming of the internet and cheaper large-scale storage technologies, public health agencies with sufficient resources began transitioning to web-accessible collections of public health data, and, more recently, to automated messaging of the same information.[3][4][5]

Application

In the United States and other parts of the world, public health informatics is practiced by individuals in public health agencies at the national, state, and larger local health jurisdiction levels. Additionally, research and training in public health informatics takes place at a variety of academic institutions. In the United States, the bulk of public health informatics activities takes place at the state and local level, in the state departments of health and the county or parish departments of health. In other parts of the world the bulk of activities may occur at a national level, with local jurisdictions reporting directly to an appropriate government or health-related entity. Activities may include[3][4]:

- collecting and storing vital statistics such as birth and death records.

- collecting reported communicable disease cases from doctors, hospitals, and laboratories for infectious disease surveillance.

- sharing infectious disease statistics and trends with other entities, including the public.

- collecting child immunization and lead screening information.

- collecting and analyzing emergency room data to detect early evidence of biological threats.

- collecting hospital capacity information to allow for planning of responses in case of emergencies.

As part of the collection and application of public health data, several challenges still exist. Some entities may simply not be aware they need to report data to other entities. A lack of resources of either the reporter or collector may also hinder reporting and sharing of data. In some parts of the world, a lack of interoperability of data interchange formats (which can be at the purely syntactic or at the semantic level) may lead to under- or non-reported public health data. Finally, variations in reporting requirements across the states, territories, and localities pose challenges, which itself may lead to variability of incoming data to public health jurisdictions, requiring greater data quality standards.[5]

Informatics

Due to the complexity and variability of public health data, like health care data generally, the issue of data modeling presents a particular challenge. Flat data sets for statistical analysis were the norm; however, today's requirements of interoperability and integrated sets of data across the public health enterprise require more sophistication. The relational database is increasingly the norm in public health informatics. Designers and implementers of the many sets of data required for various public health purposes must find a workable balance between very complex and abstract data models and simplistic, ad hoc models that untrained public health practitioners come up with and feel capable of working with.

Another challenge is found in the need to extract usable public health information from the mass of available heterogeneous data. The public health informaticist is thus required to become familiar with a variety of analysis tools, ranging from business intelligence tools to produce routine or ad hoc reports, to sophisticated statistical analysis tools and geographic information systems (GIS) to expose the geographical dimension of public health trends.

In the United States

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia has played an important role in public health and infectious disease informatics. The agency's Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services (CSELS; formerly OSELS[6][7]) and its Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance (DHIS; formerly PHITPO and PHSIPO[6][7]) has focused on advancing the state of information science in these realms, applying digital information technologies to aid in the detection and management of diseases and syndromes in individuals and populations.[8] The CDC also created the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS)[8], which includes a free comprehensive web and message-based reporting system called the NEDSS Base System (NBS), used for managing and transmitting reportable disease data.[9]

Since 2002, the CDC has promoted the idea of the Public Health Information Network to facilitate the transmission of data from various partners in the health care industry and elsewhere (hospitals, clinical and environmental laboratories, doctors' practices, pharmacies) to local health agencies, then to state health agencies, and then to the CDC. At each stage the entity must be capable of receiving the data, storing it, aggregating it appropriately, and transmitting it to the next level.[10] To promote interoperability between the NBS and other informatics systems, the CDC has also encouraged the adoption of several standard vocabularies and messaging formats from the health care world. The most prominent of these are the Health Level 7 (HL7) standards for health care messaging, the LOINC system for encoding laboratory test and result information, and the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) vocabulary of health care concepts.[9]

A typical example of data transmissions to the CDC would be infectious disease data, which hospitals, labs, and doctors are legally required to report to local health agencies. The local health agencies must then report to their state public health department and the states must report in aggregate form to the CDC. Among other uses of this received data, the CDC publishes the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), "the agency’s primary vehicle for scientific publication of timely, reliable, authoritative, accurate, objective, and useful public health information and recommendations."[11]

Notes

Some elements of this article are reused from the Wikipedia article.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yasnoff, W.A.; O’Carroll, P.W.; Koo, D. et al. (2000). "Public Health Informatics: Improving and Transforming Public Health in the Information Age". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 6 (6): 67–75. doi:10.1097/00124784-200006060-00010. PMID 18019962.

- ↑ Friede, A.; Blum, H.L.; McDonald, M. (1995). "Public Health Informatics: How Information-Age Technology Can Strengthen Public Health". Annual Review of Public Health 16: 239–252. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.16.050195.001323. PMID 7639873.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 O'Carroll, P.W. (2003). Public Health Informatics and Information Systems. Springer. pp. 790. ISBN 9780387954745. https://books.google.com/books?id=ap6uCR0Ybo4C. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lombardo, J.S.; Buckeridge, D.L. (2012). "Chapter 1: Disease Surveillance, a Public Health Priority". Disease Surveillance: A Public Health Informatics Approach. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–40. ISBN 9781118569054. https://books.google.com/books?id=-xI2Kl39ZzoC&printsec=frontcover. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Krishnamurthy, R.S.; St. Louis, M.E. (2010). "Chapter 5: Informatics and the Management of Surveillance Data". Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance. Oxford University Press. pp. 65–87. ISBN 9780195372922. https://books.google.com/books?id=FF78GCiUbwUC&pg=PA70. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Advisory Committee to the Director (July 2013). "Advisory Committee to the Director: Record of the April 25, 2013 Meeting" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. pp. 9–14. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190722192037/https://www.cdc.gov/maso/facm/pdfs/ACDCDC/20130425_CDCACD.pdf. Retrieved 06 January 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130718025323/http://www.cdc.gov/maso/pdf/CDC_Official.pdf. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance (19 June 2018). "Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 04 July 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210704090101/https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dhis/documents/dhis-fact-sheet-508.pdf. Retrieved 06 January 2022.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance (16 March 2017). "National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/about/nedss.html. Retrieved 06 January 2022.

- ↑ "Public Health Information Network Functions and Specifications, Version 1.2" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 December 2002. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111023111340/http://www.cdc.gov/phin/library/archive_2002/PHIN_Functions_Specifications_121802.pdf. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ↑ "About the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Series". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 4 March 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/about.html. Retrieved 21 March 2020.