Journal:Making the leap from research laboratory to clinic: Challenges and opportunities for next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnostics

| Full article title | Making the leap from research laboratory to clinic: Challenges and opportunities for next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnostics |

|---|---|

| Journal | mBio |

| Author(s) | Goldberg, B.; Sichtig, H.; Geyer, C.; Ledeboer, N.; Weinstock, G.M. |

| Author affiliation(s) |

Children’s National Medical Center, Food and Drug Administration, American Society for Microbiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine |

| Primary contact | Email: George dot Weinstock at jax dot org |

| Year published | 2015 |

| Volume and issue | 6(6) |

| Page(s) | e01888-15 |

| DOI | 10.1128/mBio.01888-15 |

| ISSN | 2150-7511 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported |

| Website | http://mbio.asm.org/content/6/6/e01888-15.full |

| Download | http://mbio.asm.org/content/6/6/e01888-15.full.pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS) has progressed enormously over the past decade, transforming genomic analysis and opening up many new opportunities for applications in clinical microbiology laboratories. The impact of NGS on microbiology has been revolutionary, with new microbial genomic sequences being generated daily, leading to the development of large databases of genomes and gene sequences. The ability to analyze microbial communities without culturing organisms has created the ever-growing field of metagenomics and microbiome analysis and has generated significant new insights into the relation between host and microbe. The medical literature contains many examples of how this new technology can be used for infectious disease diagnostics and pathogen analysis. The implementation of NGS in medical practice has been a slow process due to various challenges such as clinical trials, lack of applicable regulatory guidelines, and the adaptation of the technology to the clinical environment. In April 2015, the American Academy of Microbiology (AAM) convened a colloquium to begin to define these issues, and in this document, we present some of the concepts that were generated from these discussions.

Minireview

Use of next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS) (Table 1) in infectious disease diagnostics has progressed slowly over the past 10 years despite continued advances in sequencing technology. The first commercial NGS platform, the GS20 sequencer from 454 Life Sciences, which was originally released in 2005[1][2], resulted in a more than 100-fold increase in the amount of microbial genomic sequence data produced in a day compared to preceding instruments. Despite the growing body of literature and research broadly applying sequencing-based technology to disease pathophysiology, epidemiology, and clinical diagnostics, the clinical microbiology laboratory has yet to widely adopt NGS technology. As microbiology laboratories are faced with a wealth of innovative and often costly molecular technologies, the role of NGS in clinical infectious disease diagnostics needs to be carefully evaluated.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A number of highly publicized case reports and clinical studies have showcased the application of NGS as a single diagnostic tool with the potential to be broadly applicable to infectious disease diagnostics. Metagenomic (Table 1) sequencing has demonstrated its ability to identify microbial pathogens where traditional diagnostics have otherwise failed. For example, it is estimated that 63% of encephalitis cases go undiagnosed despite extensive testing.[3] Several cases in the literature have successfully employed NGS to diagnose rare, novel, or atypical infectious etiologies for encephalitis, including cases of infection by Leptospira[4], astrovirus[5], and bornavirus.[6] In one case, 38 different diagnostic tests had been conducted and failed to yield an actionable answer before a single NGS assay was performed, which identified the pathogen.[4] Similarly, the utilization of metagenomic NGS identified divergent astrovirus clades in a pair of patients with encephalitis and demonstrated the unusual zoonotic potential of a group of these viruses.[7]

Another promising application of NGS technology is hospital infection control surveillance programs and community outbreak investigations.[8] By conducting whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (Table 1), organisms can be identified at the subspecies/strain level based on the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Table 1) and other variants (Table 1) in their genotype. WGS through NGS technology offers greater precision than do more-traditional typing tools such as multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, which may assist in refining outbreak investigations and better guide infection control interventions.[9] Because WGS analysis requires significant amounts of sequencing data, traditional sequencing methods preclude the use of WGS analysis for outbreak investigations. However, NGS platforms can generate the large volume of data needed for SNP or variant analysis and have led to a rapid expansion in the use of WGS for public health investigations. For example, WGS using NGS technology was applied to investigate an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome caused by an unusual strain of Escherichia coli in Germany[10], the origins of the 2010 Haitian Vibrio cholerae epidemic[11], a series of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in a neonatal intensive care unit[12], and the origins of a series of nosocomial carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections[13], among many others.

While identification of causative microorganisms of disease is the chief responsibility of clinical microbiology laboratories, conducting antimicrobial resistance testing to guide therapy is among the most important tests conducted in the laboratory. NGS has the potential to suggest antimicrobial resistance through identification of known resistance genes.[14] Although WGS is in the early stages of development, studies have suggested that WGS can be used to predict antibiotic resistance with performance characteristics approaching those of traditional phenotypic testing. Stoesser et al.[15] demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 97%, respectively, when using WGS to predict antibiotic resistance for clinical isolates of E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Comparative genomic sequencing has also been used to identify daptomycin resistance due to point mutations in metabolic genes that occurred during therapy for two cases of vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia which were ultimately fatal.[16][17] Earlier application of WGS might have detected these point mutations and guided therapy. However, it has not been established if WGS can be broadly applied to the full spectrum of pathogenic bacteria, particularly those with a diverse armamentarium of resistance mechanisms. WGS analysis of antimicrobial resistance genes could be particularly beneficial for slow-growing or difficult-to-culture organisms and organisms that elude phenotypic testing altogether. The use of WGS is not limited to the detection of bacterial resistance genes. WGS has also been applied for the following purposes: detection of low-level drug resistance among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) “escape” variant populations (e.g., protease inhibitor [PI] and reverse transcriptase minor sequence variants) and coreceptor tropism (CCR5 and CXCR4) and analyses that are not possible using current genotypic and phenotypic HIV assays.[18] These successes and potential applications of WGS analysis have been made possible by the advance of NGS technology, which provides the tools to produce useful WGS data.

Metagenomic shotgun sequencing (mWGS) (Table 1) is often used to study microbial communities in human disease in order to identify correlative or causative relations. Such communities comprise hundreds of different taxa of bacteria, viruses, and fungi and other eukaryotic microbes. Many of these organisms are difficult to culture, and culture-independent methods of performing comprehensive sampling of these complex communities have been the major obstacle to analysis. NGS is currently the best available analytical approach to profile microbiomes (Table 1) for this purpose. To date, NGS has helped elucidate the role of the lung and gut microbiomes in both general health and various diseases, including obesity, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis (CF), metabolic syndrome, type II diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.[19][20][21][22][23] As NGS continues to expand our knowledge base on metagenomics, microbiome analysis may produce diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers to guide therapeutic decisions.

There is a long-standing precedent in clinical microbiology laboratories to adopt new technology that complements or supplants existing “gold standard” testing. The viral culture bench is all but extinct in most clinical laboratories, with PCR-based molecular assays currently dominating viral diagnostics. Nonviral microbial diagnostics have been relatively slow to adopt molecular technology, but this is rapidly changing with a new generation of molecular diagnostics that utilize specific PCR primers for different bacterial, parasitic, and fungal targets. Several of these multiplex assays have already received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance and offer laboratories an attractive and easy way to detect clinically relevant microbial pathogens. Similarly to the impact of PCR technology, microbial NGS diagnostics offer another step forward in the quality and quantity of information that could potentially be provided to clinicians and patients. In April 2015, the American Academy of Microbiology (AAM) conducted a colloquium to critically evaluate the trends in the use of NGS for infectious disease diagnostics. Below, we describe some of the concepts that evolved from the AAM’s NGS colloquium (report to be published).

Next-generation sequencing

DNA sequencing technology was previously dominated by procedures using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (also referred to as Sanger sequencing) (Table 1) for close to 30 years. In the mid-2000s, a number of new methods began to appear, commonly referred to as the “next-generation sequencing methods.” The first method that was widely commercialized was the “pyrosequencing” method, a method that formed the basis for the 454 Life Sciences instruments for about 10 years until the company closed in 2015. These instruments had a major impact on microbial genomics and became the leading platform for producing whole-genome sequences from individual bacteria as well as the platform of choice for sequencing 16S rRNA (Table 1) genes in microbiome analyses.

Since the advent of NGS, there has been an ongoing expansion of sequencing methods and instruments as well as continual improvements in the quality, quantity, and cost of sequences that are produced. The spectrum of common and available instruments current as of July 2015 is shown in Table 2, which indicates the considerable range in characteristics of NGS options.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

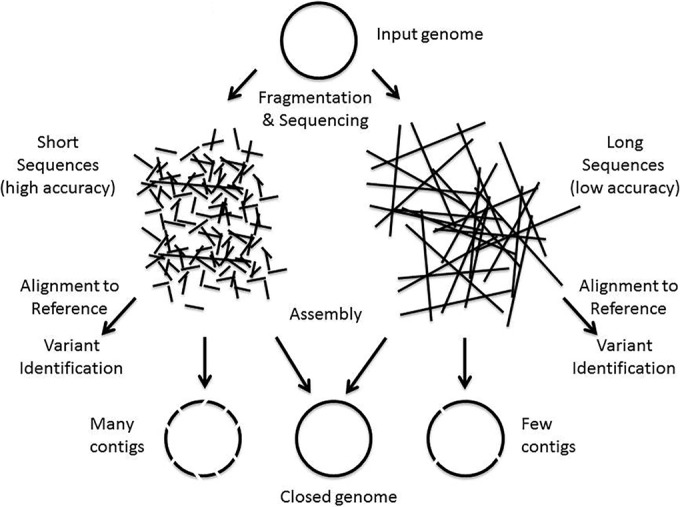

An understanding of how these characteristics match the various NGS applications is useful to appreciate the strengths or limitations of different sequencing approaches. To sequence a single microbial genome, the genome is fragmented into manageable-size pieces, which are then used in WGS (Fig. 1).

|

Depending on the sequencing platform, this can produce sequences (i.e., reads) (Table 1) that range from hundreds of bases to thousands or tens of thousands of bases in length. When the goal is to produce a microbial genome, the reads are assembled into a single genome sequence using a variety of computational strategies. Often, the assembly (Table 1) leaves gaps, and the individual chunks of genomic sequence that result are called contigs (Table 1). When identifying variants in the genome (e.g., for typing or tracking), the reads are directly aligned with a reference genome (Table 1) where the sequence variants are determined. The smaller the length of sequence read, the more contigs and gaps that are produced during the assembly process. Hence, there is a preference for longer sequence reads. To obtain a complete sequence without gaps, one often uses both short and long reads to combine the strengths of these various sequencing approaches.[24] However, the platforms producing shorter reads are often less expensive and can yield large amounts of data. Moreover, the accuracy of base calls comprising the sequence read is also important. The lower the accuracy of the read, the more reads (i.e., coverage) that are required to obtain good contigs, ultimately driving up the sequencing costs. In addition, when reads have errors, it is harder to identify the true sequence variants. At present, platforms that produce longer reads tend to have lower accuracy and users have to consider the tradeoffs between the various platforms when designing a project.

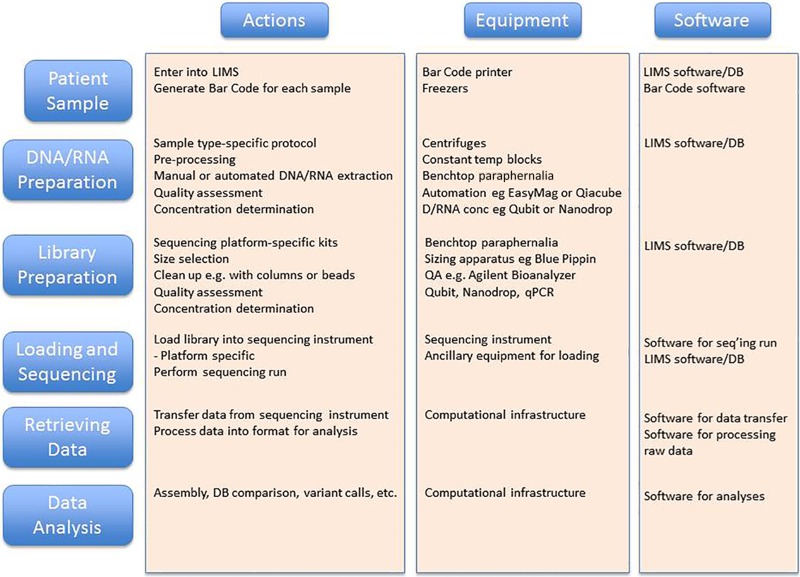

Another major application for NGS is metagenomic sequencing. In this case, one starts with a particular specimen type such as stool, saliva, a nasal swab, etc., with the goal of determining the bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microbes that are present. Following DNA extraction, a series of processing and bioinformatics steps are performed to produce NGS data for analysis (Fig. 2), analogous to the whole-genome sequence of an individual microbe described above; however, in this case the method is applied to a mixture/community of microbes. While the genomic sequences produced can be assembled, because of the various abundances of organisms, there is often not enough sequence from rarer organisms to produce a complete genome, and assembly results in very short contigs for these genomes in the mixture. More commonly, the sequence reads are aligned against databases of many (typically thousands) genome sequences to identify the likely source organism for the sequence. The abundance of such source organisms is estimated from the number of reads that match their genomes. In this way, one can identify and estimate the abundance of organisms that are present in the original patient sample.

|

The high throughput of NGS allows data to be produced from many individual bacteria/samples in a single sequencing run of hours to days. This is a vast improvement over the early days of bacterial sequencing when a single bacterial genome project could take years. Likewise, because a metagenomic sample is complex and contains hundreds of taxa at abundances ranging over many orders of magnitude, previously it was not possible to accurately assess the community structure by culture-based methods or traditional Sanger sequencing, which could handle only cultivable organisms or hundreds of sequences at best. With the availability of NGS, it is now possible to obtain millions or more of sequences per run, thus enabling deep sampling and more descriptive analysis of the microbial community on a truly useful level.

Clinical applications

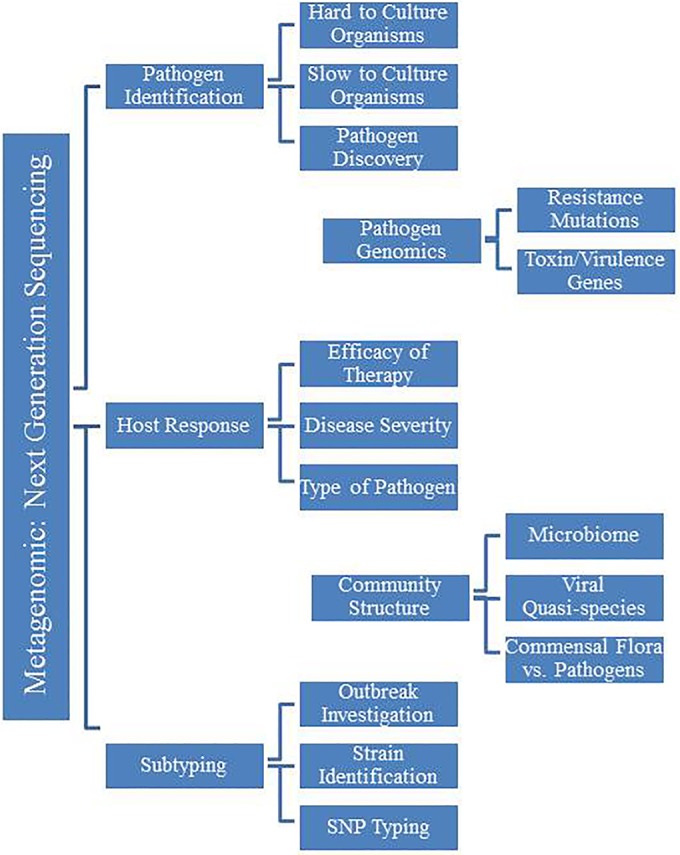

The potential clinical applications of NGS are vast and engage clinical microbiology at every level of the development process, such as outbreak tracking across the country, hospital infection control surveillance, pathogen discovery, mutation detection in a specific isolate, identification of multiple pathogens in a single sample, identification of viral quasispecies, and individual host response to infection (Fig. 3). These tests are poised to revolutionize infectious disease diagnostics and the practice of clinical microbiology. Initial reports of NGS applications for clinical diagnostics first appeared more than five years ago; however, the technology has not yet entered routine use within clinical microbiology laboratories. Reports continue to appear in the medical literature of individual case studies or small-scale applications of NGS to clinical microbiology, but experience remains limited. The technology itself is still hobbled by the enormous amount of basic research and resources needed to transform this technology into a robust clinical application for infectious disease diagnostics. To date, the medical community is still awaiting large-scale clinical trials to establish the utility of NGS in different clinical settings; however, comprehensive funding and incentives for these studies are limited.

|

Although NGS has the potential to provide a huge volume of information to health care practitioners with respect to both microbial characteristics and the host response to disease, it will be necessary to determine strategies to pragmatically deal with this data barrage. Many of the potential applications to clinical medicine are not known. In the field of bacteriology, NGS has particular limitations in determining which organisms are merely “innocent bystanders” or are colonizers rather than active pathogens. For instance, a potentially pathogenic microorganism identified from one specimen type, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or synovial fluids, which are typically thought to be sterile, may be normal in the skin, gut, or mouth.

The potential implications for physicians/practitioners, and particularly antimicrobial stewardship, are staggering. One important question: if currently a certain percentage of practitioners treat patients with antibiotics even when lacking evidence of a bacterial pathogen, what will they do when presented with a pathogen that is likely (but not absolutely) a contaminant?

More importantly, a paradigm shift in the understanding of molecular diagnostics will be necessary for clinicians and professionals in the clinical microbiology community. Both molecular diagnostics and traditional culture-based technology have their strengths and weaknesses. One of the strengths of NGS assays is the ability to detect many microorganisms directly from a patient sample without needing additional testing or a priori knowledge of the type of pathogen. NGS can potentially detect viruses, bacteria, yeast, fungi, and parasites without the need for additional individual testing. However, both traditional technologies and NGS assays have limitations in detection that can be clearly defined. But while culture absolutely indicates the presence of living organisms, the presence of organismal DNA is less definitive.

Ultimately, clinical studies and eventually clinical trials examining patient outcomes will be necessary to reinforce the cost savings and benefit of using NGS-based clinical tests for the diagnosis of infectious disease. A prominent issue with such studies is the scarcity of funding. Because of how expensive these analyses are to conduct, they can be unattractive to industry and require a certain amount of patience and determination from the clinical community to perform correctly and in an economically wise manner. Moreover, such studies require establishing fundamentals such as standard operating procedures for NGS diagnostics. At present, there is no standardization between studies, much less between different institutions. All aspects of the NGS diagnostic pipeline remain variable, including clinical specimen collection, sequencing parameters, data analysis/interpretation, and data reporting. Such details must be established before clinical outcomes can be systematically examined.

Determining the optimal approach to advance the use of NGS poses serious challenges. For example, how would a clinical laboratory determine the analytical validation of a device that could potentially pick up any known or novel pathogens? While the majority of clinical infections are typically attributed to a finite number of bacterial, viral, and fungal pathogens, a main attraction of NGS for clinical diagnosis is the ability to capture rare or unsuspected, yet potentially actionable, pathogens. It is tremendously appealing to identify both pathogen and patient genomic sequence information for everything from virulence genes to strain-level sequence variants to an assessment of the patient response to infection or effectiveness of antibiotic therapy. The advancement of NGS technology into pathogen genomics could potentially provide supplemental descriptive or predictive information regarding the potential antimicrobial resistance gene profile of the microorganism and allow for more rapid selection of appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Although early studies have reported promising results for antimicrobial resistance detection, the most valuable piece of antimicrobial resistance information is the antimicrobials to which the organism is susceptible[15][25], and it is unclear what the strength of NGS for predicting susceptibility as opposed to resistance will be. Additionally, as bacteria and viruses are constantly evolving new resistance mechanisms, reference databases would have to be continuously updated to include novel resistance genes and mutations in order for NGS to be an effective predictor. Thus, it seems unlikely that the clinical laboratory will be moving away from phenotypic confirmation in the near future. Additional clinical studies are needed to explore the capabilities of NGS assays for these applications and the potential partnership between NGS and culture-based assays.

References

- ↑ Margulies, M.; Egholm, M.; Altman, W.E. et al. (2005). "Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors". Nature 437 (7057): 376–80. doi:10.1038/nature03959. PMC PMC1464427. PMID 16056220. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1464427.

- ↑ Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S. et al. (2012). "Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems". Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2012: 251364. doi:10.1155/2012/251364. PMC PMC3398667. PMID 22829749. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3398667.

- ↑ Brown, J.R.; Morfopoulou, S.; Hubb, J. et al. (2015). "Astrovirus VA1/HMO-C: An increasingly recognized neurotropic pathogen in immunocompromised patients". Clinical Infectious Diseases 60 (6): 881-8. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu940. PMC PMC4345817. PMID 25572899. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4345817.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wilson, M.R.; Naccache, S.N.; Samayoa, E. et al. (2014). "Actionable diagnosis of neuroleptospirosis by next-generation sequencing". New England Journal of Medicine 37 (25): 2408-17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401268. PMC PMC4134948. PMID 24896819. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4134948.

- ↑ Naccache, S.N.; Peggs, K.S.; Mattes, F.M. et al. (2015). "Diagnosis of neuroinvasive astrovirus infection in an immunocompromised adult with encephalitis by unbiased next-generation sequencing". Clinical Infectious Diseases 60 (6): 919-23. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu912. PMC PMC4345816. PMID 25572898. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4345816.

- ↑ Hoffmann, B.; Tappe, D.; Höper, D. et al. (2015). "A Variegated Squirrel Bornavirus Associated with Fatal Human Encephalitis". New England Journal of Medicine 372 (2): 154-62. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1415627. PMID 26154788.

- ↑ Quan, P.L.; Wagner, T.A.; Briese, T. et al. (2010). "Astrovirus encephalitis in boy with X-linked agammaglobulinemia". Emerging Infectious Diseases 16 (6): 918-25. doi:10.3201/eid1606.091536. PMC PMC4102142. PMID 20507741. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4102142.

- ↑ GenomeWeb staff reporter (7 August 2015). "CDC Earmarks $2.3M for NGS, Bioinformatic Approaches to Combat Infectious Disease". GenomeWeb. Genomeweb LLC. https://www.genomeweb.com/research-funding/cdc-earmarks-23m-ngs-bioinformatic-approaches-combat-infectious-disease. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Turabelidze, G.; Lawrence, S.J.; Gao, H. et al. (2013). "Precise dissection of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak by single nucleotide polymorphism analysis". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 51 (12): 3950-4. doi:10.1128/JCM.01930-13. PMC PMC3838074. PMID 24048526. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3838074.

- ↑ Rasko, D.A.; Webster, D.R.; Sahl, J.W. et al. (2011). "Origins of the E. coli strain causing an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Germany". New England Journal of Medicine 365 (8): 709-17. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1106920. PMC PMC3168948. PMID 21793740. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3168948.

- ↑ Chin, C.S.; Sorenson, J.; Harris, J.B. et al. (2011). "The origin of the Haitian cholera outbreak strain". New England Journal of Medicine 364 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012928. PMC PMC3030187. PMID 21142692. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3030187.

- ↑ Azarian, T.; Cook, R.L.; Johnson, J.A. et al. (2015). "Whole-genome sequencing for outbreak investigations of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the neonatal intensive care unit: Time for routine practice?". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 36 (7): 777–785. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.73. PMC PMC4507300. PMID 25998499. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4507300.

- ↑ Snitkin, E.S.; Zelazny, A.M.; Thomas, P.J. et al. (2012). "Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing". Science Translational Medicine 4 (148): 148ra116. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004129. PMC PMC3521604. PMID 22914622. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3521604.

- ↑ Dunne Jr., W.M.; Westblade, L.F.; Ford, B. (2012). "Next-generation and whole-genome sequencing in the diagnostic clinical microbiology laboratory". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 31 (8): 1719-26. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1641-7. PMID 22678348.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Stoesser, N.; Batty, E.M.; Eyre, D.W. et al. (2013). "Predicting antimicrobial susceptibilities for Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates using whole genomic sequence data". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 68 (10): 2234-44. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt180. PMC PMC3772739. PMID 23722448. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3772739.

- ↑ Arias, C.A.; Panesso, D.; McGrath, D.M. et al. (2011). "Genetic basis for in vivo daptomycin resistance in enterococci". New England Journal of Medicine 365 (10): 892-900. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1011138. PMC PMC3205971. PMID 21899450. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3205971.

- ↑ Tran, T.T.; Panesso, D.; Gao, H. et al. (2013). "Whole-genome analysis of a daptomycin-susceptible enterococcus faecium strain and its daptomycin-resistant variant arising during therapy". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 57 (1): 261-8. doi:10.1128/AAC.01454-12. PMC PMC3535923. PMID 23114757. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3535923.

- ↑ Fisher, R.; van Zy, G.U.; Travers, S.A. et al. (2012). "Deep sequencing reveals minor protease resistance mutations in patients failing a protease inhibitor regimen". Journal of Virology 86 (11): 6231-7. doi:10.1128/JVI.06541-11. PMC PMC3372173. PMID 22457522. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3372173.

- ↑ Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P. et al. (2005). "Obesity alters gut microbial ecology". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (31): 11070-5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504978102. PMC PMC1176910. PMID 16033867. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1176910.

- ↑ Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J. et al. (2010). "A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing". Nature 464 (7285): 59-65. doi:10.1038/nature08821. PMC PMC3779803. PMID 20203603. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3779803.

- ↑ Graessler, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhong, H. et al. (2013). "Metagenomic sequencing of the human gut microbiome before and after bariatric surgery in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: Correlation with inflammatory and metabolic parameters". Pharmacogenomics Journal 13 (6): 514-22. doi:10.1038/tpj.2012.43. PMID 23032991.

- ↑ Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J. et al. (2011). "Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease". Nature 472 (7341): 57-63. doi:10.1038/nature09922. PMC PMC3086762. PMID 21475195. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3086762.

- ↑ Price, K.E.; Hampton, T.H.; Gifford, A.H. et al. (2013). "Unique microbial communities persist in individual cystic fibrosis patients throughout a clinical exacerbation". Microbiome 1 (1): 27. doi:10.1186/2049-2618-1-27. PMC PMC3971630. PMID 24451123. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3971630.

- ↑ Koren, S.; Schatz, M.C.; Walenz, B.P. et al. (2012). "Hybrid error correction and de novo assembly of single-molecule sequencing reads". Nature Biotechnology 30 (7): 693-700. doi:10.1038/nbt.2280. PMC PMC3707490. PMID 22750884. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3707490.

- ↑ Gordon, N.C.; Price, J.R.; Cole, K.; et al. (2014). "Prediction of Staphylococcus aureus antimicrobial resistance by whole-genome sequencing". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 52 (4): 1182-91. doi:10.1128/JCM.03117-13. PMC PMC3993491. PMID 24501024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3993491.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.