Book:Justifying LIMS Acquisition and Deployment within Your Organization/Organizational, economic, and practical justifications for a LIMS/Economic considerations and justifications

2.2 Economic considerations and justifications

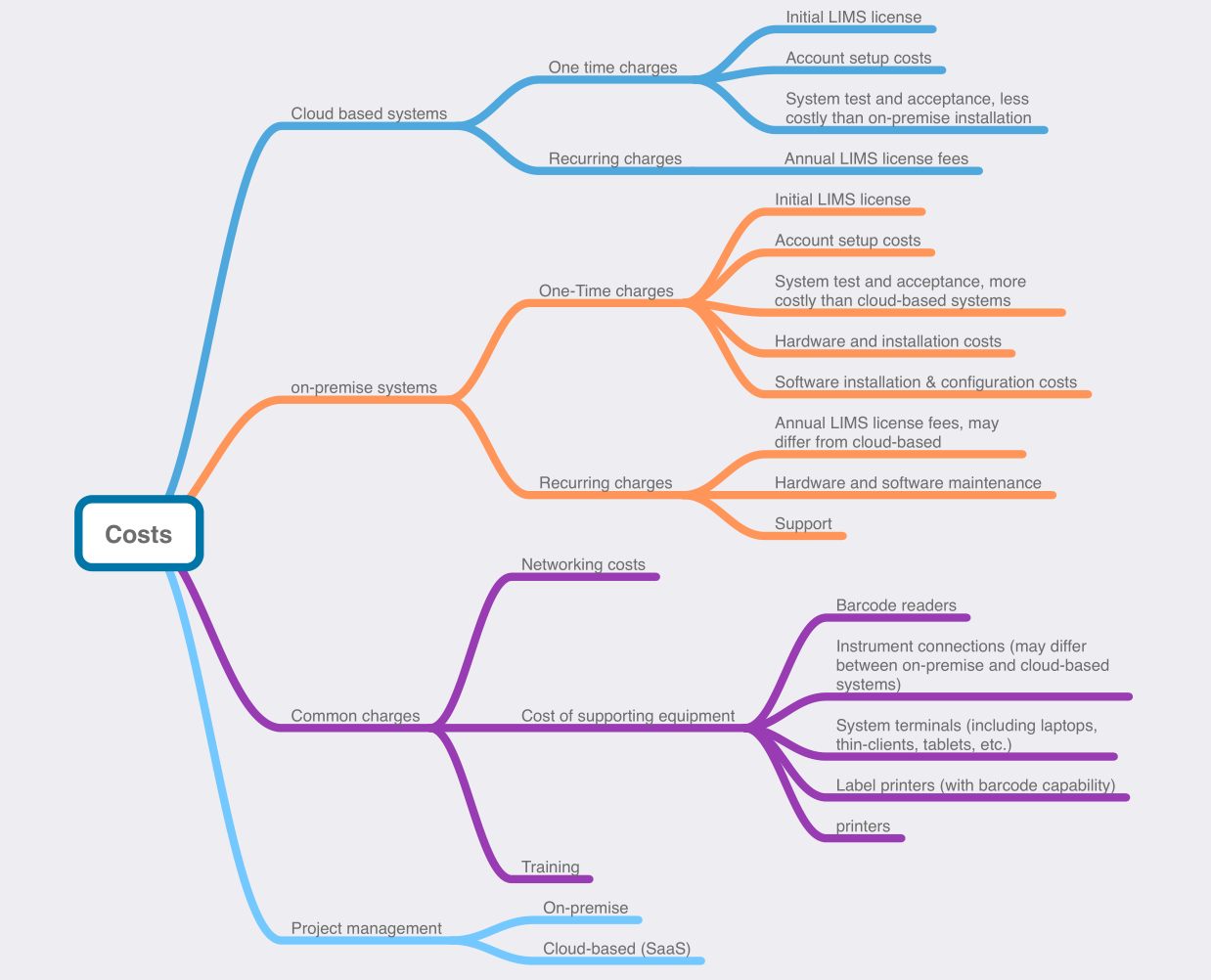

Figure 2 shows the key cost-based considerations of a basic LIMS installation project, with details for both on-premises and cloud-based systems. Depending on the vendor, there are potential additional costs. For example, any additional instrument interfacing costs may depend on the vendor's approach, the number and type of instruments in your lab, and so on. The same applies to connections to other software systems (e.g., accounting, statistical data systems, and others). Instrument and software integration costs aside, Figure 2 also brings up:

- License, maintenance, and support costs: Whether one-time or recurring, there will be a license fee for the software. And it will require scheduled maintenance and support for when things go wrong.

- Acceptance and validation testing costs: Unless the vendor includes this in their implementation package, you may have to budget for the necessary tests to ensure the system is meeting the needs and requirements of your laboratory and its stakeholders.

- System and account configuration costs: You could try to have your soon-to-be system administrator manually add user accounts, configure roles, and make other configuration changes, or it may make sense to have the vendor do the work for you in advance, for a price.

- Data migration costs: If your lab already has electronic data of some sort, it may be viewed as mission-critical, with a need to modify and migrate it to the new LIMS in an acceptable format. Such data migration projects can be time-consuming and costly, depending on the complexity and "dirtiness" of the data being imported.

- Networking costs: Whether installed locally or in the cloud, some sort of networking is required (unless you’re working in a tiny lab with a single computer, running software locally). The client instances of the LIMS will need to electronically communicate with the server instance, or the web-based access screen will need to electronically communicate with the vendor hosting the LIMS in the cloud. This means local networking costs and/or a highly-dependable internet connection.

- Supporting equipment and hardware costs: From barcode readers and label printers to system terminals and document printers, the implementation of your LIMS may require supporting equipment that, in tandem with the LIMS, will improve workflows and expedite laboratory tasks. The LIMS introduces improved sample and specimen tracking using barcode labels and scanners, which benefits the lab, but is useless without the additional equipment. If the LIMS is to be hosted on-premises, IT hardware will also likely need to be acquired.

- Training costs: Some vendors may include a set amount of training with their implementation package, while others may not. Your lab is likely going to want to hit the ground running with the new LIMS, which means well-trained personnel, with full documentation and recorded training videos. As new personnel are on-boarded, your lab may not want to be the one responsible for training, opting to ask the vendor to run the employee through training.

- Project management costs: Acquiring and implementing a LIMS is a project, full stop. The costs associated with project management may be handled internally, through normal hourly- or salary-based payment of personnel and managers for their organizational duties. However, some labs may not have the internal resources and experience to field such a project, requiring either a consultancy or even hiring the LIMS vendor to work with a lab stakeholder to oversee the project.

|

As you'll see in the following subsections, the method of accounting for these and other costs associated with LIMS implementation, and their justification, will be similar to that of acquiring supporting laboratory equipment: what are the costs, and what are the benefits, both tangible and intangible?

2.2.1 On-premises vs. cloud LIMS

The economics behind the on-premises LIMS are generally different from those of the cloud-based LIMS. An on-premises system ultimately sees the system administrator taking responsibility for most or all aspects of the system. This includes:

- Hardware selection: This includes the computer and associated components (e.g., printer, power backup, software backup, etc.). Additionally, the admin will need to find a place to put the computer and make arrangements with IT support for their services.

- LIMS installation: This includes installation of the operating system, LIMS software, and any underlying components (e.g., database software, support tools, etc.). This may be done alone or with the vendor's and IT services' assistance.

- LIMS validation and testing: The admin will be responsible for full system validation and testing. This significantly increases the workload of project management and support.

The LIMS-specific software costs and process of using this type of LIMS implementation include the following:

- Payment of the initial LIMS license and account setup fees is a one-time charge. These charges are usually based on the number of concurrent users of the system (sometimes referred to as “seats”). If you have six people in your lab, each can have their own login (meeting regulatory requirements), but only the specified number of concurrent users can access the software simultaneously. For example, with six accounts, and a license for two seats, two people can be working on the LIMS simultaneously. It may help to review several use cases internally, as well as their associated costs, to get a sense for how many accounts you need and can afford. Table 3 provides an example of a tabular view one might take with calculating license costs for several use cases.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Once the software has been installed and passes the necessary qualification testing, the next step is to configure the system to reflect your lab's requirements. This is more demanding than a cloud-based software as a service (SaaS) implementation since the project manager (PM) is responsible for all aspects of the work instead of being divided between the PM and the vendor; the vendor may provide guidance for some of this work based on their experience. This would include setting up test descriptions (including test and product limits), personnel data, relevant initial customer data, report formats, access controls, etc., whatever you define as needed to have a functioning system. This would not include instrument connections or connections to other systems. While those can be and are done, they usually entail an additional cost. Issues like that, and the details of their inclusion, are beyond the scope of this document, but you should be able to include them easily. The costs for instrument connections can vary widely depending on the devices' nature, use, and vendor’s support.

- Once the system is set up, a system test and acceptance process begins as a part of a complete system acceptance/validation program. This compares the contents of the user requirement document to the functioning systems. This allows you to verify that the system works according to your needs and specifications. This is part of the validation process but not the entire process.

- Recurring charges include the annual license renewal fee, usually a fraction of the initial license cost. In addition, there would be hardware support costs, software maintenance fees (e.g., underlying components, including the operating system), backup systems annual fees (e.g., power, hardware, software), and IT support costs. Support can involve software and hardware vendors, facilities management (e.g., backup power), and IT support.

Cloud-based SaaS LIMS, on the other hand, are hosted on the vendor's server and is ready to be accessed and used once it is initialized with your lab's specific details. No local software installation is needed. The costs and process of using this software implementation include the following considerations:

- Access to SaaS LIMS entails the payment of the initial LIMS license and account setup fees. These are one-time fees. As noted above, these charges are usually based on the number of concurrent users of the system (i.e., “seats”). A similar set of account-based use cases (Table 3) can be used to calculate various account scenarios and their license costs.

- The next step is configuring the system to reflect your lab's requirements. This tends to be easier than an on-premises solution and would include setting up test descriptions (including test and product limits), personnel data, relevant initial customer data, report formats, access controls, and whatever else you define as needed to have a functioning system. This would not include instrument connections or connections to other systems. As noted earlier, while those can be and are done, they usually entail an additional cost.

- Once the system is set up, a system test and acceptance process allows you to verify that the system is working according to your needs and specifications. This is part of the validation process but not the entire process.

- Recurring charges include the annual license renewal fee, usually a fraction of the initial license cost. This is usually simpler than with an on-premises solution.

Table 4 provides a comparison of aspects of on-premises LIMS with cloud-based SaaS LIMS.

| ||||||

In the end, from a purely cost-focused perspective, the cloud-based SaaS LIMS may make more sense for the modern lab. The previous chapter's Table 1 compared 1980s-era concessions, considerations, and justifications for maintaining an existing lab's operations vs. acquiring and deploying an on-premises LIMS. While those same aspects largely pertain to today's on-premises LIMS installation, most of the costs of hardware, installation, IT support, data storage, etc., go away with a cloud-based LIMS installation. Suddenly the economic justification for a LIMS looks rosier due to the reduced costs associated with having your LIMS securely hosted by another entity. The core cloud LIMS could be available on an annual basis for less than the cost of one person, easily justified through productivity improvements, improved data governance, and improved regulatory compliance. For example, the average annual salary for a government lab worker is $43,757 (2022 average)[1], which is very close to the base pay for a lab technician in Boston, Massachusetts (2023).[2]

The first year’s charges for a basic cloud-based LIMS with two concurrent users, including one-time and annual recurring charges, are less than that yearly salary value. The yearly recurring charge is less than a third of that technician's income. As you add on functions such as instrument interfacing (see the next subsection), both the initial and recurring costs will increase, and so will the productivity gains through faster, more efficient data entry and automation. Additionally, a cloud-based LIMS largely eliminates the need for on-site server hardware, software installation, and IT support. (Note: It is not our position that people should be laid off to justify the added cost of a LIMS, but some future hiring may be avoided or deferred.) Yes, training still needs to be provided, as does support for instrument connections. However, the latter can be phased in on an as-needed basis.

2.2.2 Common and add-on costs

It's important to note that regardless of the implementation approach, some costs are common to both on-premises and cloud-based SaaS systems. They include:

- Networking: Networking costs include wiring the lab and any recurring charges for support and the communications services themselves. These might come from a corporate budget or payments to an internet service provider. This should also include security protections against malware and intrusion. In the SaaS model, system security is provided by the vendor for the database system. An on-premises system is the lab’s or IT service's responsibility. Even with the SaaS model, your company has to provide network security to prevent the internet access services from becoming an entry point for hackers into your lab network.

- Training: Everyone needs to be educated in the use of the LIMS. Some, like systems administrators, are educated to a higher degree than others. There is an initial charge for this when the system is introduced and a recurring charge as it evolves and new lab personnel come on board. Education for on-premises systems is more demanding since someone designated within the lab or IT services would function as the system administrator and handle all system modifications, including LIMS and underlying software upgrades.

- Printers: The truly paperless lab may exist, but it is a rarity. People like paper; it's easy to work with and reassuring when you hold your results in your hand.

- System access: Everyone needs system terminals that provide access to the LIMS and other systems in the lab. These include laptops, full computers, tablets, smartphones, and thin-client terminals.

- Project management: Project management exists as a separate line item that comes in two forms, regardless of whether an on-premises or SaaS installation is used, though on-premises implementations would entail considerably more effort. One is the work the vendor does in implementing your requests and providing the initial support, while the other is the work that you do to generate user requirements, evaluating vendors, and managing the process from "we need a LIMS" to "its running and meets all specified requirements," and all the meetings and justifications that occur in between. That also includes having lab personnel educated on the use of the system. This is the basis for LIMS software process validation. Note that project management would be both an initial charge and a recurring cost. The latter accounts for updates to the user-controlled aspects of the system, such as adding new tests, clients, etc. (though software updates in SaaS environments are the vendor’s responsibility).

Beyond those costs common to both implementation types, there are add-on capabilities. These can include technologies such as barcodes and instrument connections, as well as others. While this document doesn't intend to review all or a majority of the add-on capabilities, we will look at the two mentioned to illustrate a template for their justification. (Note, however, that barcode and instrument connection capabilities would not be realized with paper-based systems and are difficult to undertake with spreadsheet implementations.)

Let's first address barcodes. Barcode technologies are an important alternative to manual data entry, greatly reducing the error rate.[3] This is significant because the longer an error goes undetected, the greater the impact and cost repercussions. Take for example the early 1990s work of George Labovitz and Yu Sang Chang[4], who created the 1-10-100 rule, which states that data entry errors multiply costs exponentially according to the stage at which they are identified and corrected. They reasoned that it costs you a dollar to fix a data entry error as soon as it's made, it will cost $10 at the next step of the process, perhaps when it is used as part of a calculation. If the error persists and is reported as part of an analytical sample report, it may cost $100 to fix, plus the embarrassment caused by the error. Those dollar figures are in 1992 valuations; in today’s dollars (2023), $100 then equals roughly $215 today.[5]

The extent of error rate reduction that barcode technologies offer will vary by barcode print quality, how clean the label is, the scanning equipment used, the user's proficiency, and the sample container's geometry. Plex Systems provides an error rate of 1 per 300 characters for manual entry, with it potentially being as good as 1 per 36 trillion characters for barcodes (though this may be under ideal conditions).[6] ZIH Corp. states that the error rate of barcode data entry “has been widely estimated at one error per 3 million characters.”[7] Peak Technologies states that data entered by barcodes are four times less likely to contain errors than that entered by hand.[8] Finally, a CDC study reports that data entry errors are “nearly six times as likely from manual entry systems than from point-of-care test barcoding systems.”[9] There seems to be a disparity between studies that could be attributed to the difference between character counts and data entry measures where the data elements consist of multiple characters.

As you might expect, any statement about error reduction will have significance throughout the LIMS justification. In addition to error reduction, barcodes are faster than manual entry, reducing it from 10 to 20 seconds per entry to possibly two or three. In addition, in some regulated environments, manual data entry requires verification by a second person, increasing the cost significantly. Barcodes can impact the sample login process, sample location and inventory, results entry, and almost any step in the sample processing sequence.

Similar to Table 3, which provides a tabular template for examining user account costs, Table 5 gives you one possible way to tabulate a cost-benefit analysis of barcode technology.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Beyond error limiting, using barcode technologies opens other opportunities to streamline lab operations and improve client relations for the lab. One possible example is shown in Table 6, demonstrating how a cooperative effort between the lab and its clients can result in labor reduction and faster sample processing. In that example, you could organize a system where sample containers and preprinted test request sheets with barcoded sample labels (keyed to a barcode on the test request form) are provided to a client who participates in the sample login process through a client access portal. This streamlines operations reduces errors, and could give the client a cost reduction in testing that would reflect their efforts.

| |||||||||||||||

The above points are particularly notable for labs that produce income from testing work, such as contract labs. These labs may improve working relationships with corporate internal clients by speeding up sample processing. If such labs are able to increase cooperative relationships with clients with the help of barcodes and pre-labeled sample containers, our cost-benefit analysis from Table 5 changes slightly, as seen in Table 7.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Next we address IDS connections to the LIMS. A laboratory's processes and procedures (P&P) provide the steps for preparing samples and carrying out an analysis. Lab instruments generate the data and results that sample submitters are seeking. Anything we can do to streamline that process will reduce operating costs, increase the rate at which samples can be handled, and reduce errors. We can replace manual efforts at organizing work and entering results into a LIMS with an electronic system by connecting IDSs to LIMS. Table 8 compares the outcome of using an IDS and LIMS manually with developing an electronic connection between the two.

| ||||||

The electronic connection between the IDS and LIMS eliminates most of the need for manual operations at both the IDS and the LIMS. It also provides a basis for fully automating processes, with minimal demands on lab personnel, freeing them for more demanding tasks. The benefit is considerable cost savings in people's time and effort, with faster processing of samples from sample login, through processing, and review/release of results.

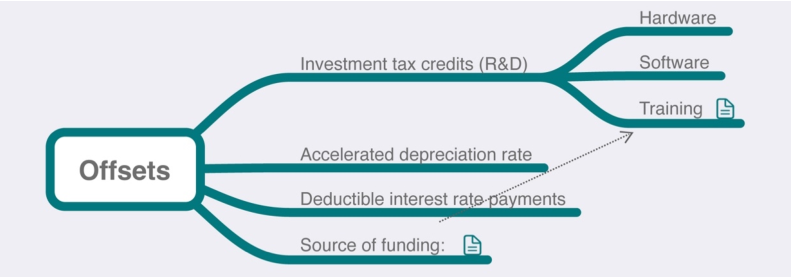

2.2.3 Factors that can offset costs

In Table 1 of the previous chapter, we noted that some labs in the 1980s were considering the potential benefit of offsetting LIMS acquisition and deployment costs through investment tax credits, accelerated depreciation rate, and deductible interest rate payments. This concept largely still holds true today. Figure 3 demonstrates this in further detail.

|

Investment tax credits are available for hardware purchases and software development.[10][11] How these apply to your project depends on the specifics of the work that is planned and the current state of the tax laws. The lab is best suited to consult with a finance or tax professional to best determine how such credits actually work. This also includes matters such as choosing to accelerate depreciation of fixed assets so as to defer tax liabilities until later[12], or to deduct interest expenses on qualifying income-producing activities.[13]

An additional point worth looking at is how training is going to be handled. Will it be through the lab's budget or a general corporate training function? Splitting the project across multiple budgets (e.g., training, IT, etc.) may make it easier to fund and to take advantage of tax breaks.

References

- ↑ "Occupation Index: Laboratory Working". FederalPay.org. 2023. https://www.federalpay.org/employees/occupations/laboratory-working. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "How much does a Lab Technician make in Boston, MA?". Glassdoor. 14 June 2023. https://www.glassdoor.com/Salaries/boston-lab-technician-salary-SRCH_IL.0,6_IM109_KO7,21.htm. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "1D vs 2D Barcodes — What’s the Difference?". Brady Worldwide, Inc. 4 October 2022. https://www.bradyid.com/applications/product-and-barcode-labeling/1d-vs-2d-barcodes. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Labovitz, George; Chang, Yu Sang; Rosansky, Victor (1992). Making quality work: A leadership guide for the results-driven manager. Oliver Wight Ltd. ISBN 978-0-939246-54-0.

- ↑ Webster, I.. "$100 in 1992 is worth $216.77 today". CPI Inflation Calculator. Alioth LLC. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1992?amount=100. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "Barcoding 101 for Manufacturers: What You Need to Know to Get Started". Plex Systems. http://media.techtarget.com/Syndication/ENTERPRISE_APPS/Barcoding_WP.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "Barcode Labeling in the Lab — Closing the Loop of Patient Safety" (PDF). ZIH Corp. March 2016. https://www.zebra.com/content/dam/zebra_new_ia/en-us/solutions-verticals/vertical-solutions/healthcare/white-paper/barcode-labeling-lab-white%20paper-en-us.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Kallenbach, J. (18 March 2020). "Barcodes in the Lab". Peak Technologies. https://www.dasco.com/resources/learning-center/2020/03/18/barcodes-in-the-lab/. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Laboratory Medicine Best Practices Workgroup (February 2012). "Effective practices for reducing patient specimen and laboratory testing identification errors in diverse hospital settings" (PDF). Laboratory Medicine Best Practices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/labbestpractices/pdfs/CDC_BarCodingSummary.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Powell, G.; Peters, J. (20 February 2023). "Don’t forget technology investments when it comes to the R&D tax credit". Explore Our Thinking. Plante Moran. https://www.plantemoran.com/explore-our-thinking/insight/2020/08/is-your-business-getting-the-rd-tax-credit-it-deserves. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "R&D Tax Credits for the Technology & Software Industry". BDO USA, P.A. 11 March 2021. https://www.bdo.com/insights/tax/r-d-tax-credits-for-the-technology-software-industry. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ "Accelerated depreciation definition". AccountingTools. 7 June 2023. https://www.accountingtools.com/articles/what-is-accelerated-depreciation.html. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ↑ Kagan, J. (8 March 2023). "Tax-Deductible Interest: Definition and Types That Qualify". https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/tax-deductible-interest.asp. Retrieved 19 July 2023.