User:Shawndouglas/sandbox/sublevel1

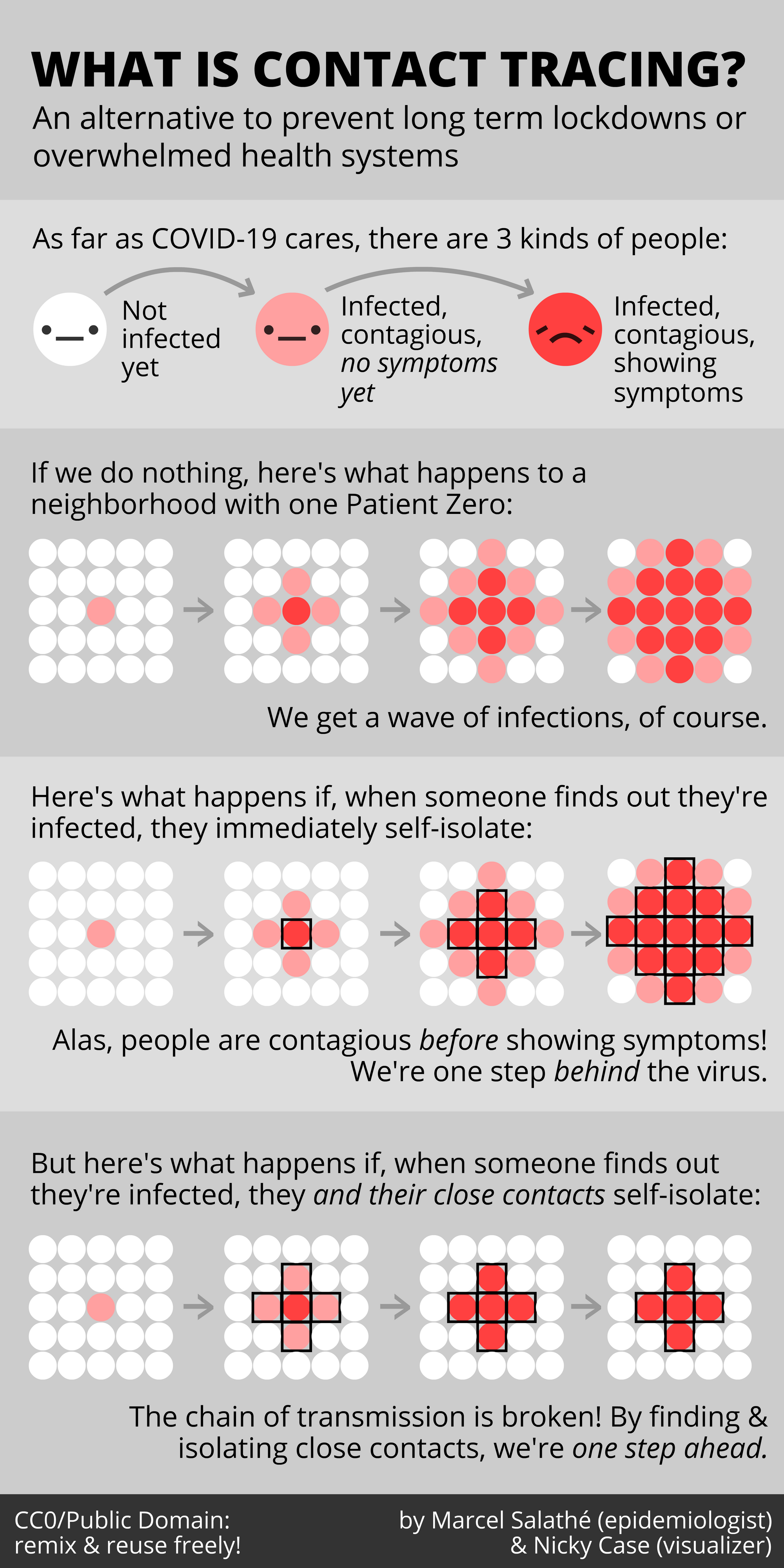

Contact tracing is a public health process that involves the determination of who a patient had specific contact with while infectious, then informing, supporting, and maintaining contact with those effected individuals in order to reduce the spread of an infection.[1] The seeds of contact tracing may go as far back as late fifteenth and early sixteenth century efforts to control infection rates of syphilis among prostitutes in part of Europe.[2] However, the practice was adopted more vigorously in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in Great Britain for tracking cases of communicable diseases such as measles[3] and sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis and gonorrhea.[4] Further inroads were made in the United States in the early 1930s with its efforts to reduce sexually transmitted diseases among U.S. troops.[5]

Throughout it all, contract tracing has been predominately a manual effort. However, the technological age has brought with it both social promise and privacy questions in regards to the application of informatics to contact tracing. In the mid-2000s, the use of Wi-Fi and RFID technology in Singapore hospital settings "to provide an alternative to tedious and error-prone manual contact tracing" was being reported in academic literature.[6] Since then, the use of informatics tools in contact tracing has increased, seeing practical application in combating severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)[7], Ebola[8], and tuberculosis.[9] As such, it should not be surprising that early in the COVID-19 pandemic, contract tracing was also being discussed within the context of both manual and digital tracing efforts.[1][10][11][12]

Contact tracing using digital tools, however, comes with both benefits and challenges.[13][14] Digital contact tracing tools have the potential to make contract tracing quicker and more efficient than manual processes. People can forget who they may have been in close contact with, for example, but with digital tracing, past location data can be mined to provide a clearer picture. As a result, with more accurate data, local and state policy-making efforts can be more nimbly tailored to current needs, and the effectiveness of those efforts can be better monitored.[9][6][13][15] However, several challenges also exist, primarily with social and cultural perceptions of the technology's acceptability and the privacy concerns surrounding it.

Social acceptability and trust around the world

The social acceptability and trust put into contact tracing applications and the governments that use them is of significant concern. An April 2020 "blitz" survey of the Flemish Region of Belgium showed that only 51 percent of respondents had "no objection to a CORONA-app, under strict conditions."[16] As legal researcher Domenico Orlando points out, many contact tracing applications like Italy's Immuni app, however, require at least 60 percent of the population to participate for it to be effective.[17] He adds that while whether or not "trust and social acceptance will follow is an unknown variable" when it comes to digital contact tracing, having a strong set of legal protections in place—such as those found with E.U. data protection law and the efforts of the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) to create data protection guidelines for digital surveillance tools[18]—at least makes the technology more feasible.[17] Political and cultural context also plays a role in social acceptance. Countries like South Korea and states like Taiwan—in comparison to mainland China—arguably have seen greater adoption of digital surveillance due to a more relaxed political context[19], though attempts by the citizenry to be vigilantes who shame and discriminate others based on contact tracing data may work counter to that overall adoption rate.[13] Recent past experiences with digitally tracing MERS and SARS outbreaks in both cases, however, have probably played an even greater role in the success of convincing those governments' citizenry to voluntarily participate.[15] Similar adoption success can be seen in a Singapore poll that showed 70 percent of respondents were open to installing its government's voluntary TraceTogether app, which is based on the privacy-preserving protocol BlueTrace.[15]

Challenges in the U.S.

In the United States, adopted use of contract tracing apps has been much more sporadic. Several cultural factors contribute. First and foremost, Americans' reluctance to answer calls from unknown numbers is continuing to increase. A First Orion 2019 Spam Call Trends and Projections Report found that more than 40 percent of calls received are spam calls, and 70 percent of Americans do not answer calls from an unknown number.[20] A December 2019 TrueCaller report found that robocalls in the U.S. "increased from 7% [in 2018] to a staggering 35% – which means that more than every third spam call a user gets is a robocall."[21] This issues get complicated even further by lack of enforcement on "spoofing," the practice of making a phone number appear to originate locally, or from a specific business. Even if a call looks legitimate, it may actually not be.[20][22] As Vice writer Casey Johnston suggests, given spam and spoofing practices and the related lack of enforcement, "until the United States takes its scam and spam call problem seriously, we’re probably going to be in the contact-tracing dark ages for a very long time."[22]

Second, overall trust in the federal government to do what's best and resolve problems has some catching up to do. September 2020 polls by the Pew Research Center[23] and Gallup[24] showed faith in overall federal government near all-time lows. As Lydia Saad of Gallup concluded in her 2020 analysis: "As the country is engaged in critical efforts to combat the medical, economic and societal effects of the global coronavirus pandemic, Americans' trust in the federal government to handle domestic issues is near its lowest point in Gallup trends since 1972, as is their trust in the executive and legislative branches, public officials generally, and the American people themselves."[24] A few positive signs have shown, with overall public trust in government making a small uptick and "trust in the federal government to provide accurate information about COVID-19" rising with the January 2021 presidency change.[25][26] Yet as long as overall trust in the federal government remains low, it will continue to be difficult to roll out any significant contract tracing efforts across the nation.

Third, the ebbs and flows of case numbers—with surges in November 2020 and again in the summer of 2021 with the delta variant[27][28]—make the number of cases to track tough to overcome. This is often compounded by the time it takes to get results, often too long to stem the flow of new infections.[29] A lack of a clear and organized national strategy for contract tracing, unlike the European Union[30], punctuates the challenges of getting more people to use contact tracing apps.[31]

Privacy and other issues

The preservation of user privacy and sensitive identifying data are also vital considerations in digital tracing apps. The previously mentioned BlueTrace protocol and its open-source reference implementation OpenTrace strive to address most of those concerns when "logging Bluetooth encounters between participating devices to facilitate contact tracing, while protecting the users’ personal data and privacy." More specifically, it strives to limit collection of personally-identifiable information, locally store and lock down encounter history, prevent third-party tracking, and provide revocable consent to store and allow use of encounter data.[32] Ultimately, these and other such solutions must ensure the anonymity of tracing data doesn't become compromised. Lew and Anderson also note that "[c]loud-based storage of anonymous identifier beacons may also threaten security, given that any centralized list of identifiers could theoretically be hacked and re-identified."[14] As noted previously, re-identified data, let alone leaked anonymized data, could lead to shaming and discrimination against individuals identified as being infected.[13]

Privacy is not solely a concern of application developers, however. Government entities should also be held responsible for better ensuring how informatics solutions are created and used for epidemiological tracking. The European Union's EDPB and its contact tracing guidelines, adopted in April 2020, offer a compromise between the societal needs of contact tracing and the individual needs of privacy. The EDPB addresses the topics of location data sources and anonymized use, as well as the recommendations and functional requirements of applications employing those data sources, concluding "that one should not have to choose between an efficient response to the current crisis and the protection of our fundamental rights: we can achieve both."[18] The U.S. CDC is less eloquent with its COVID-19 digital contact tracing guidelines, though they still stress the preference for secure data transfer mechanisms, open-source architecture, need-to-know-only access to data for public health authorities, and the ability for users to revoke data access consent at any time.[10]

Finally, most digital tracing solutions also suffer from a few additional downsides. Several researchers have expressed concerns about data accuracy and actionability issues in mobile devices that lead to false positives. These issues include[14][32]:

- inaccurate inter-device distance detection

- inaccurate exposure detection in high-density buildings with multiple walls

- inability to track duration of exposure (i.e., seconds or hours)

- failures with the underlying technology itself, including BlueTooth or the operating system

The future

Despite these and other drawbacks, various governments around the world have found greater success at managing the COVID-19 pandemic with digital contact tracing. Huang et al. in the Harvard Business Review wonder if the successes reported in South Korea, Taiwan, and other parts of the East could be replicated in the United States and other Western democracies[15]:

Can Western democracies achieve the results seen in East Asia without emulating their means? Probably not. There is likely a fundamental conflict between these requirements and deeply entrenched Western liberal values, such as the expectation of privacy, consent, and the sanctity of individual rights ... At the time of publication, at least three local governments in the United States are considering adoption of a contact-tracing app developed in a project led by MIT, Reuters reports ... But for such technologies to be effective, compliance must be nearly universal. Without a government mandate in the U.S., it’s hard to imagine universal voluntary adoption of even a privacy-protecting tracing app.

Maybe Covid-19 is a sign of our future steady state. Different societies will make different choices about how to respond to the next pandemic. For Western democracies the time has come to either rethink our values around the tradeoff between personal privacy and public safety in a pandemic or to accelerate technology innovation and policy development that can preserve both.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (3 December 2020). "Case Investigation and Contact Tracing : Part of a Multipronged Approach to Fight the COVID-19 Pandemic". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/principles-contact-tracing.html. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Rosen, G. (2015). A History of Public Health (Revised Expanded ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9781421416021. https://books.google.com/books?id=q5yeBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA46.

- ↑ Mooney, G. (2015). "Chapter Four: Combustible Material - Classrooms, Contact Tracing, and Following-Up". Intrusive Interventions: Public Health, Domestic Space, and Infectious Disease Surveillance in England, 1840–1914. University of Rochester Press. pp. 93–120. ISBN 9781580465274. https://books.google.com/books?id=P1W3CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA93.

- ↑ Davidson, R. (1996). "‘Searching for Mary, Glasgow’: Contact Tracing for Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Twentieth-Century Scotland". Social History of Medicine 9 (2): 195–214. doi:10.1093/shm/9.2.195.

- ↑ Wigfield, A.S. (1972). "27 Years of Uninterrupted Contact Tracing: The 'Tyneside Scheme'". British Journal of Venereal Diseases 48 (1): 37–50. doi:10.1136/sti.48.1.37. PMC PMC1048270. PMID 5067063. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1048270.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lim, W.T.L. (2006). "Development of Medical Informatics in Singapore - Keeping Pace with Healthcare Challenges" (PDF). Proceedings from the 2006 Meeting of the Asia Pacific Association for Medical Informatics: 1–4. https://www.apami.org/apami2006/papers/wlim(sg).pdf.

- ↑ Zhang, Y.; Dang, Y.; Chen, Y.-D. et al. (2008). "BioPortal Infectious Disease Informatics research: Disease surveillance and situational awareness". Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Digital Government Research: 393–94. doi:10.5555/1367832.1367909.

- ↑ Schafer, I.J.; Knudsen, E.; McNamara, L.A. et al. (2016). "The Epi Info Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) Application: A Resource for Outbreak Data Management and Contact Tracing in the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola Epidemic". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 214 (Suppl. 3): S122–S136. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw272. PMID 27587635.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ha, Y.P.; Tesfalul, M.A.; Littman-Quinn, R. et al. (2016). "Evaluation of a Mobile Health Approach to Tuberculosis Contact Tracing in Botswana". Journal of Health Communication 21 (10): 1115-21. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1222035. PMC PMC6238947. PMID 27668973. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6238947.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 American Hospital Association (4 May 2020). "CDC sets preliminary standards for digital COVID-19 contact tracing tools". American Hospital Association. https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2020-05-04-cdc-sets-preliminary-standards-digital-covid-19-contact-tracing-tools. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Yan, H. (15 May 2020). "Contact tracing 101: How it works, who could get hired, and why it's so critical in fighting coronavirus now". CNN Health. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/27/health/contact-tracing-explainer-coronavirus/index.html. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Fortin, J. (18 May 2020). "So You Want to Be a Contact Tracer?". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/18/health/coronavirus-contact-tracing-jobs.html. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Waltz, E. (25 March 2020). "Halting COVID-19: The Benefits and Risks of Digital Contact Tracing". IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/halting-covid19-benefits-risks-digital-contact-tracing. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Lew, C.; Anderson, F. (14 April 2020). "‘Digital Contact Tracing’ — Advantages, Risks, & Post-COVID Applications". DeciBio. https://www.decibio.com/insights/digital-contact-tracing-advantages-risks-post-covid-applications. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Huang, Y.; Sun, M.; Sui, Y. (15 April 2020). "How Digital Contact Tracing Slowed Covid-19 in East Asia". Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-digital-contact-tracing-slowed-covid-19-in-east-asia. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Knowledge Centre Data & Society (8 April 2020). "Survey: 51% has no objection to a corona-app, under strict conditions". Knowledge Centre Data & Society. https://data-en-maatschappij.ai/en/news/survey-corona-app. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The EDPB Guidelines on digital tools against Covid-19, a brief comment". KU Leuven Centre for IT & IP Law. 12 May 2020. https://www.law.kuleuven.be/citip/blog/the-edpb-guidelines-on-digital-tools-against-covid-19-a-brief-comment/. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 European Data Protection Board (April 2020). "Guidelines 04/2020 on the use of location data and contact tracing tools in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak". European Data Protection Board. https://edpb.europa.eu/our-work-tools/our-documents/guidelines/guidelines-042020-use-location-data-and-contact-tracing_en. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Nazeer, T. (7 April 2020). "Digital Surveillance and 'Technological Totalitarianism'". Byline Times. https://bylinetimes.com/2020/04/07/the-coronavirus-crisis-digital-surveillance-and-technological-totalitarianism/. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 First Orion (2019). "Spam Call Trends and Projections Report - Summer 2019" (PDF). First Orion. http://firstorion.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/First-Orion-Scam-Trends-Report_Summer-2019.pdf. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Kok, K.F. (3 December 2019). "TRUECALLER INSIGHTS: TOP 20 COUNTRIES AFFECTED BY SPAM CALLS & SMS IN 2019". TrueCaller. https://truecaller.blog/2019/12/03/truecaller-insights-top-20-countries-affected-by-spam-calls-sms-in-2019/. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Johnston, C. (31 August 2020). "The Real Reason Contact Tracing Is Doomed in the US: Spam Calls". Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/935vvz/the-real-reason-contact-tracing-is-doomed-in-the-us-spam-calls. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Pew Research Center (14 September 2020). "Americans’ Views of Government: Low Trust, but Some Positive Performance Ratings". https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2020/09/14/americans-views-of-government-low-trust-but-some-positive-performance-ratings/. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Saad, L. (29 September 2020). "Trust in Federal Government's Competence Remains Low". Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/321119/trust-federal-government-competence-remains-low.aspx. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Pew Research Center (17 May 2021). "Public Trust in Government: 1958-2021". https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/05/17/public-trust-in-government-1958-2021/. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Durkee, A. (26 January 2021). "Trust In Government Information On Covid Surges Under Biden, Poll Reports". Forbes. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210126160459/https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2021/01/26/trust-in-government-information-on-covid-19-surges-under-biden-poll-reports/. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Stone, W. (24 November 2021). "How Do We Stop This Surge? Here's What Experts Say Could Help". NPR Shots. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/11/24/937178668/are-more-lockdowns-inevitable-or-can-other-measures-stop-the-surge. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Doheny, K. (31 August 2021). "As Delta Surges, Contact Tracing Re-Takes COVID Center Stage". WebMD Health News. https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20210831/delta-surge-contact-tracing. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ Khazan, O. (31 August 2020). "The Most American COVID-19 Failure Yet". The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/08/contact-tracing-hr-6666-working-us/615637/.

- ↑ European Commission (19 October 2020). "Coronavirus: EU interoperability gateway for contact tracing and warning apps – Questions and Answers". European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_20_1905. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Uberti, D. (21 October 2020). "Disjointed Covid-19 Apps Across U.S. Raise Questions About Tech’s Role". The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/disjointed-covid-19-apps-across-u-s-raise-questions-about-techs-role-11603272613. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Bay, J.; Kek, J.; Tan, A. et al. (2020). BlueTrace: A privacy-preserving protocol for community-driven contact tracing across borders. pp. 1–9. https://bluetrace.io/static/bluetrace_whitepaper-938063656596c104632def383eb33b3c.pdf.

Citation information for this chapter

Chapter: 4. Workflow and information management for COVID-19 (and other respiratory diseases)

Edition: Fall 2021

Title: COVID-19 Testing, Reporting, and Information Management in the Laboratory

Author for citation: Shawn E. Douglas

License for content: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Publication date: September 2021