Book:LIMS Selection Guide for Food Safety and Quality/Introduction to food and beverage laboratories/Food and beverage labs, then and now

1. Introduction to food and beverage laboratories

Food and beverage laboratories help develop and ensure the safety and quality of the food, beverages, and nutritional supplements humans and animals consume. From creating new flavor enhancers for food to ensuring the quality and safe consumption of a wine, these labs play a vital role in most parts of the world where processed food and agricultural products are produced. These labs are found in the private, government, and academic sectors and provide many different services, including (but not limited to)[1]:

- reverse engineering,

- claims testing,

- contaminate testing,

- batch variation testing,

- extractable and leachable testing,

- allergen testing,

- shelf life testing,

- non-routine quality testing, and

- packaging testing.

If you have ever enjoyed a candy bar, soda, or snack cake, know that a laboratory and food scientists were behind its production. Even if you don't care much for such processed foods, a laboratory is still involved in the quality and safety testing of raw fruits and vegetables, milk, and nuts. And when food supplies become contaminated, government testing labs are often in the thick of determining the source of the contamination as quickly as possible before more people become ill.

But what of the history of the food and beverage lab? What of the roles played and testing conducted in them? What do they owe to safety and quality? This chapter more closely examines these questions and more.

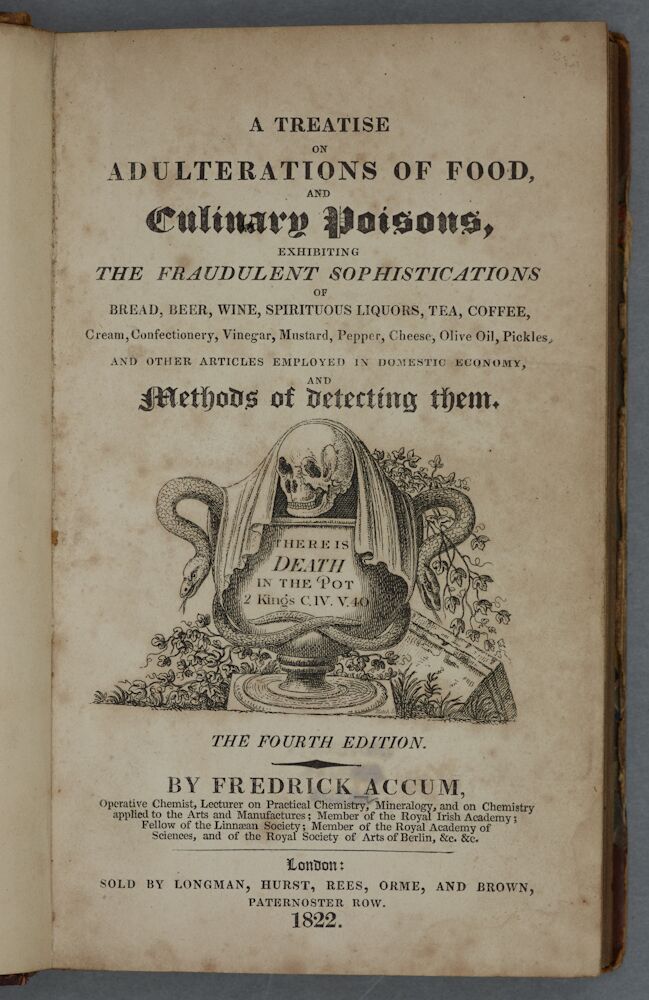

1.1 Food and beverage labs, then and now

The history of laboratory-based food and beverage tasting is a scattered one, with little being documented about foodborne illness and food safety until the nineteenth century. With a better understanding of bacteria and their relationship to disease, however, more was being said about the topic by the mid- to late-1800s.[2] In the U.S. Northeast during the 1860s, recognition was growing concerning the threat that tainted milk originating from dairy cows being singularly fed distillery byproducts had to human health. Not only was the milk generated from such cows thin and low in nutrients, but it also was adulterated with questionable substances to give it a better appearance. This resulted in many children and adults falling ill or dying from consuming the product. The efforts of Dr. Henry Coit and others in the late 1800s to develop a certification program for milk—which included laboratory testing among other activities—eventually helped plant the seeds for a national food and beverage safety program.[3]

Roughly around the same time, during the 1880s, Britain saw more public health awareness develop in regards to digestive bacterial infections. "As deadlier infections retreated," argues social historian Anne Hardy, "food poisoning became an increasing concern of local and national health authorities, who sought both to raise public awareness of the condition as illness, and to regulate and improve food handling practices."[4] This led to further efforts from public health laboratories to promote the reporting and tracking of food poisoning cases by the 1940s.[4]

With the recognition of bacterial and other forms of contamination occurring in foodstuffs, beverages, and ingredients, as well as growing acknowledgement of the detrimental health effects of dangerous adulterations with toxic substances, additional progress was made in the realm of regulating and testing produced food and beverages. Events of interest along the way include[5][6][7][8][9][10]:

- By 1880, the first of many municipal laboratories dedicated to testing food and beverage adulteration came into use in France. A focus was made on watered-down wines early on, but Frances's municipal food safety labs quickly began addressing other foods, beverages, and ingredients.

- The Pure Food and Drug Act and Beef Inspection Act were passed in 1906 in response to food quality issues in packing plants, on farms, and other areas of food production.

- In 1927, the U.S. Food, Drug, and Insecticide Administration (shortened to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or FDA not long after) was formed to better enforce the Pure Food Act.

- By 1945, Clostridium perfringens was being identified as a common cause of foodborne illness[2], and today it is recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of the top five provocateurs of foodborne illness.[11]

- The seeds of the hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) quality control method were planted in 1959, when Pillsbury began working with NASA to ensure safe foods for astronauts. The value of Pillsbury and NASA's methodology became apparent to the food and beverage industry by 1972, and other organizations began adopting HACCP for food safety.

- The Fair Packaging and Labeling Act of 1966 brought standardized, more accurate labeling to food and beverages.

- The Food Quality Protection Act of 1996 mandated HACCP for most food processors and improved pesticide level calculations.

- FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) was enacted in 2011, giving the FDA more enforcement authority and tools to improve the backbone of the U.S. food and water supply.

- In December 2021, the Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods (LAAF) amendment to the FSMA was approved, providing for an accreditation program for laboratories wanting to further participate in the critical role of ensuring the safety of the U.S. food supply through the "testing of food in certain circumstances."

This progression of scientific discovery and regulatory action has surely managed to reduce risks to U.S. food and beverage consumers, though not without complication and complexity.[12][13] As the U.S. population has grown over the past 100 years, it has become more difficult to have a sufficient number of inspectors, for example, to examine every production facility or farm and all they do, necessitating a risk assessment approach to food and beverage safety.[6][7][14] As such, the laboratory is undoubtedly a critical component of risk-based safety assessments of food and beverage products.

References

- ↑ Nielsen, S. (2015). Food Analysis Laboratory Manual (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 177. ISBN 9781441914620. https://books.google.com/books?id=i5TdyXBiwRsC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Roberts, Cynthia A. (2001). The food safety information handbook. Westport, CT: Oryx Press. pp. 25-28. ISBN 978-1-57356-305-5.

- ↑ Lytton, Timothy D. (2019). "Chapter 2: The Gospel of Clean Milk". Outbreak: foodborne illness and the struggle for food safety. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 24-64. ISBN 978-0-226-61154-9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hardy, A. (1 August 1999). "Food, Hygiene, and the Laboratory. A Short History of Food Poisoning in Britain, circa 1850-1950" (in en). Social History of Medicine 12 (2): 293–311. doi:10.1093/shm/12.2.293. ISSN 0951-631X. https://academic.oup.com/shm/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/shm/12.2.293.

- ↑ Stanziani, A. (2016). "Chapter 9. Municipal Laboratories and the Analysis of Foodstuffs in France Under the Third Republic: A Case Study of the Paris Municipal Laboratory, 1878-1907". In Atkins, P.J.; Lummel, P.; Oddy, D.J. (in English). Food and the city in Europe since 1800. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-58261-0. OCLC 950471625. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=OPYFDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA105.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Redman, Nina (2007). "Chapter 1: Background and History". Food safety: a reference handbook. Contemporary world issues (2nd ed ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-048-3. OCLC ocm83609690. https://www.worldcat.org/title/mediawiki/oclc/ocm83609690.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stevens, K.; Hood, S. (2019). "Chapter 40. Food Safety Management Systems". In Doyle, Michael P.; Diez-Gonzalez, Francisco; Hill, Colin. Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers (5th edition ed.). Washington, DC: ASM Press. pp. 1007-20. ISBN 978-1-55581-997-2.

- ↑ Detwiler, Darin S. (2020). "Chapter 2: "Modernization" started over a century ago". Food safety: past, present, and predictions. London [England] ; San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 11-23. ISBN 978-0-12-818219-2.

- ↑ "Background on the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA)". Food and Drug Administration. 30 January 2018. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/background-fda-food-safety-modernization-act-fsma. Retrieved 07 December 2022.

- ↑ Douglas, S. (21 February 2022). "FDA Food Safety Modernization Act Final Rule on Laboratory Accreditation for Analyses of Foods: Considerations for Labs and Informatics Vendors". LIMSwiki.org. https://www.limswiki.org/index.php/LII:FDA_Food_Safety_Modernization_Act_Final_Rule_on_Laboratory_Accreditation_for_Analyses_of_Foods:_Considerations_for_Labs_and_Informatics_Vendors. Retrieved 07 December 2022.

- ↑ "Foodborne Germs and Illnesses". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 March 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html. Retrieved 07 December 2022.

- ↑ Lytton, Timothy D. (2019). "An Introduction to the Food Safety System". Outbreak: Foodborne Illness and the Struggle for Food Safety. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1-23. ISBN 978-0-226-61154-9.

- ↑ Floros, John D.; Newsome, Rosetta; Fisher, William; Barbosa-Cánovas, Gustavo V.; Chen, Hongda; Dunne, C. Patrick; German, J. Bruce; Hall, Richard L. et al. (26 August 2010). "Feeding the World Today and Tomorrow: The Importance of Food Science and Technology: An IFT Scientific Review" (in en). Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 9 (5): 572–599. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00127.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00127.x.

- ↑ Food Safety: Current Status and Future Needs. American Academy of Microbiology Colloquia Reports. Washington (DC): American Society for Microbiology. 1998. PMID 33001600. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562616/.