Book:The Laboratories of Our Lives: Labs, Labs Everywhere!/A framework for the laboratories of our lives/A proposed framework for organizing laboratories

2. A framework for the laboratories of our lives

It is well and good to broadly discuss laboratories and how they've impacted humanity, but classifying them is still a challenge. But why classify labs? As Professor John Blamire of Brooklyn College notes, "[h]umans like to bring order out of chaos" through classification, with hopes of revealing new insights or find patterns in otherwise complex systems.[1] Making sense of laboratories in the scope of our lives is no different really, and as such, history in hand, we look to build a framework for better visualizing and understanding how labs intersect our lives. This brief chapter proposes a framework for the organization of labs, which then lays the foundation for subsequent chapters and their explanation of the industries laboratories function in.

2.1 A proposed framework for organizing laboratories

When thinking casually about laboratories, clinical diagnostic and chemistry labs likely spring to mind. But when the layman is pressed to name more laboratory types than that, the task becomes increasingly difficult. The next logical jump is to think about all the different types of scientific study that might have a laboratory associated with it: how about biology, physics, geology, and engineering? That list could get rather long, actually, and it may be a little like throwing darts blindfolded given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of scientific research today.

So how do we better visualize how and where laboratories intersect our lives? It helps to build a framework that all laboratories could find a home within.

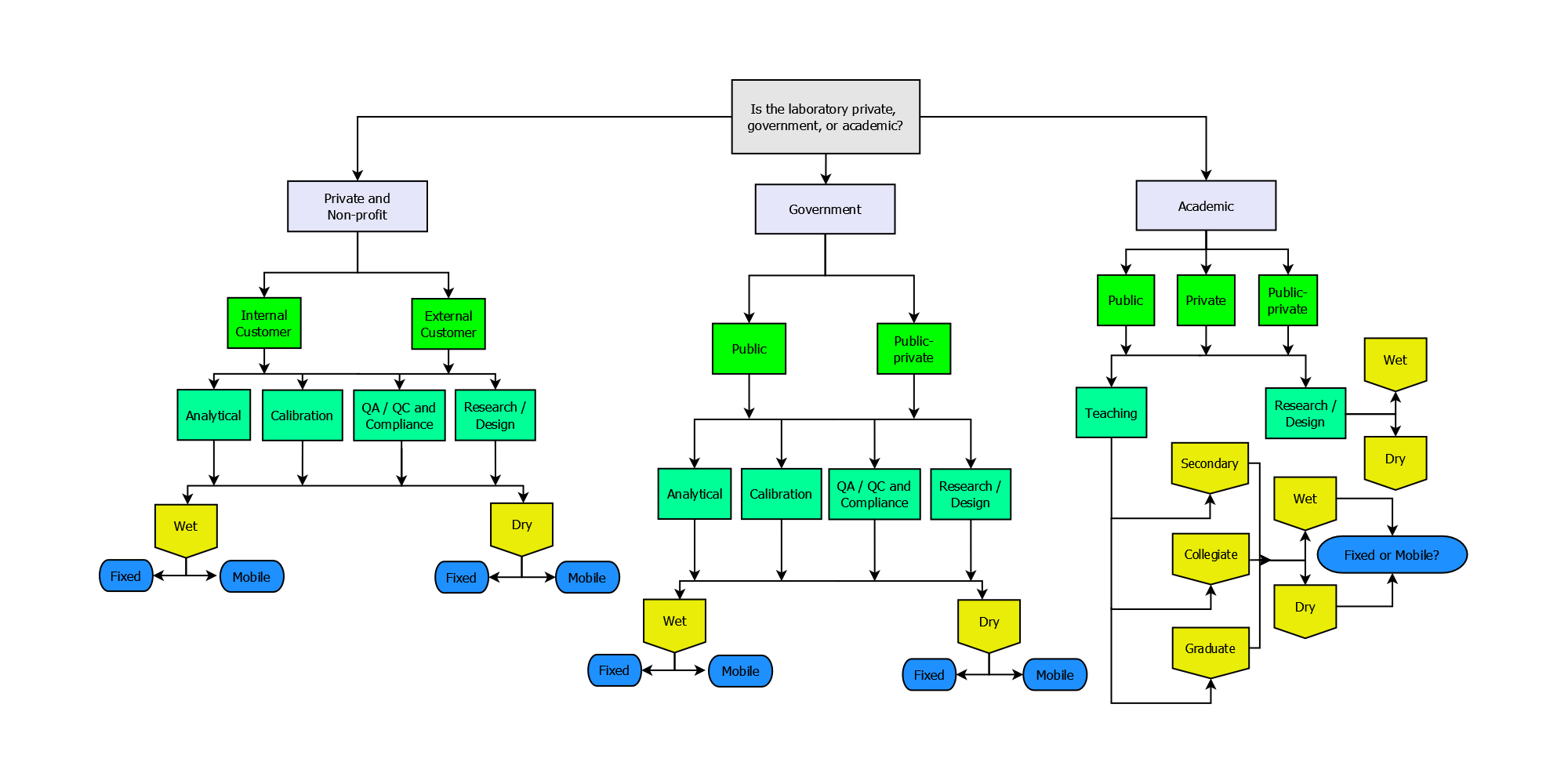

Below (Fig. 1) is a diagrammatic expression of one method of organizing laboratories of the world. The idea behind the framework is that, starting from the top, you could name a specific laboratory and be able to put it somewhere within the framework. For example:

- The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation's mobile forensics laboratory[2] would fall under Government > Public > Analytical > Dry > Mobile.

- An engineering design laboratory based within a for-profit car manufacturing company would fall under Private > Internal Customer > Research / Design > Dry > Fixed.

- A chemistry laboratory housed in a secondary school in Germany would fall under Academic > Public > Teaching > Secondary > Wet > Fixed.

|

The original inspiration for Figure 1 came from Jain and Rao's attempt to diagram Indian diagnostic laboratories in 2015.[3] While their diagram focused entirely on the clinical sphere of laboratories, it was easy to envision expanding upon their work to express laboratories of all types. Additional inspiration came from KlingStubbins' architecture textbook Sustainable Design of Research Laboratories: Planning, Design, and Operation[4], which lists several methods for organizing types of laboratories; Daniel D. Watch's Building Type Basics for Research Laboratories[5]; and Walter Hain's Laboratories: A Briefing and Design Guide.[6]

The colored sections of the diagram represent:

- Blue chalk: Sector/client type (private/non-profit, government, or academic)

- Hot green: Customer (internal/external) or partnership/role (public, private, or public-private)

- Sea green: Function (analytical, calibration, QA/QC and compliance, research/design, or teaching)

- Banana yellow: Sub-functions (wet/dry, secondary, collegiate, or graduate)

- Dodger blue: Mobility (fixed or mobile)

The benefit of this diagrammatic approach—with sector or "client type" as a starting point—becomes more apparent when we start considering the other two methods we could use to categorize laboratories, as described by KlingStubbins et al.: by science and by function. Organizing by science quickly becomes problematic, emphasizes KlingStubbins[4]:

Gone are the days when the division was as simple as biology and chemistry. New science fields emerge rapidly now and the lines between the sciences are blurred. A list based on science types would include not just biology and chemistry, but biochemistry, biophysics, electronics, electrophysiology, genetics, metrology, nanotechnology, pharmacokinetics, pharmacology, physics, and so on.

As for "function," we can look at what type of activity is primary to the lab. Is the lab designed to act as a routine analytical station; calibrate equipment; provide quality assurance (QA), quality control (QC), or compliance testing functions; function as a base for research and development (R&D); or perform more than one of these tasks? Another benefit of looking at labs by function is it helps with our organization of labs within various industries (discussed in the subsequent sections) by what they do. For example, we don't have a "manufacturing lab"; rather, we have a laboratory in a manufacturing company—perhaps making cosmetics—that serves a particular function, whether its QC or R&D. This line of thinking has utility, but upon closer inspection, we discover that we need to also look further up the chain at who's running it (sector/client type), as well as the customer or role it serves.

As such, we realize the "function" the lab serves can be integrated with client type, customer, and role to provide a more complete framework. Why? When we look at laboratories by science type—particularly when inspecting newer fields of science— we realize 1. they are often interdisciplinary (e.g., molecular diagnostics integrating molecular biology with clinical chemistry) and 2. they can serve two different functions within the same science (e.g., a diagnostic cytopathology lab vs. a teaching cytopathology lab). Rather than build a massively complex chart of science types, with numerous intersections and tangled webs, it seems more straightforward to look at laboratories by client type, customer/role, and then function, following from the architectural viewpoints presented by KlingStubbins et al. With that framework firmly in place, we can better organize an examination of where labs can be found and what roles they function under.

However, this doesn't mean looking at laboratories by science is entirely fruitless. But rather than focus directly on the sciences, why not look at the industries employing laboratory science? While there is crossover between industries (e.g., the cosmetic and petrochemical industries both lean on various chemical sciences), we can extend from Figure 1 (or work in parallel with it) and paint a broader picture of just how prevalent laboratories are in our life.

In the subsequent sections, we look at the private, government, and academic labs (i.e., client types) in various industries; provide real-life examples of labs and their specific tests; and discuss the various activities (i.e., functions) and sciences performed in them.

References

- ↑ Blamire, J. (1998). "Introduction". Classification: Bringing order out of chaos. Brooklyn College. http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/bc/ahp/CLAS/CLAS.Intro.html. Retrieved 06 July 2022.

- ↑ Stephens, B. (4 March 2015). "Inside look at FBI's new mobile forensics lab". KCTV5 News. Gannaway Web Holdings, LLC. Archived from the original on 06 August 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150806100647/http://www.kctv5.com/story/28266161/inside-look-at-fbis-new-mobile-forensics-lab. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ Jain, R.; Rao, B. (2015). "Medical diagnostic laboratories provisioning of services in India". CHRISMED Journal of Health and Research 2 (1): 19–31. doi:10.4103/2348-3334.149340.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 KlingStubbins (2010). Sustainable Design of Research Laboratories: Planning, Design, and Operation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9780470915967. https://books.google.com/books?id=yZQhTvvVD7sC&pg=PA18. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ Watch, D.D. (2001). "Chapter 2: Laboratory Types". Building Type Basics for Research Laboratories. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 37–99. ISBN 9780471217572. https://books.google.com/books?id=_EGpDgUNppIC&pg=PA37. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ Hain, W. (2003). Laboratories: A Briefing and Design Guide. Taylor & Francis. pp. 2–5. ISBN 9781135822941. https://books.google.com/books?id=HPB4AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA2. Retrieved 28 June 2022.