Histopathology

Histopathology is a branch of histology and pathology that studies and diagnoses diseases on the tissue and cellular level. While histopathology is closely related to cytopathology, the main difference is diagnostic information gained from histopathology is acquired from solid tissue samples, whereas specific disaggregated cell preparations are used in cytopathology.[1] Typically a biopsy or surgical specimen is examined by a pathologist after the specimen has been processed and histological sections have been placed onto glass slides.

Rudolf Ludwig Karl Virchow is considered by many to be one of the fathers of cellular pathology, remembered most for his collection of lectures on the topic, published as Cellular Pathology in 1858.[2][3] However, his assistant, David Paul von Hansemann also played an important role in the progress of histopathology during the 1890s, producing his book The Microscopic Diagnosis of Malignant Tumours and other important research.[4][5]

Testing

Collection

Tissues are collected typically by a type of biopsy (removal of tissue from a living subject), though other methods may be used. The type of biopsy used is often determined by the region where tissue will be removed. For example, a core biopsy may target muscle tissue via a large-bore needle. A cone biopsy targets a woman's cervix, while a Pipelle biopsy targets the endometrium, which is the inner mucous membrane of the uterus. Other types of collection include currettings, scrapings of tissue from the disease site; resectioning, a complete removal of diseased tissue; and even amputation, the complete removal of an extremity.[1]

Preparation

Fixation and sectioning

The first step of preparation is fixation, the process of placing the sample in a particular preservative substance and appropriate container for transport and/or distribution. The most commonly used fixative is 10 percent neutral buffered formaldehyde, a toxic organic compound with the formula CH2O or HCHO. Some samples may require freezing, while other special tissues like bone marrow and special procedures like electron microscopy require special fixatives. This step is vital to the diagnostic process. Without a proper fixative, tissues can degrade to the point of producing poor diagnostic sensitivity.

After the fixed sample is received, it may be bisected (smaller sample) or sectioned into blocks (larger sample) to facilitate processing and embedding. If sectioned into blocks, the resulting tissue samples may then be placed in cassettes for later ease of analysis.[1]

Dehydration, clearing, and impregnation

Before placing the sample in paraffin wax — the medium of choice in histopathology — it must be prepared to allow micro-fine slices to be cut and placed on a slide. First, the sample is dehydrated using industrial methylated spirit (IMS) or a similar alcohol. An increasing potency of IMS solutions are applied to the sample in order to remove all traces of water. Second, the remaining traces of alcohol must be removed. Alcohol and paraffin wax are not capable of mixing, causing problems if impregnation of the sample with wax is attempted. A solvent like xylene acts as a "clearing agent" to remove the alcohol from the sample, with multiple applications usually being necessary. Later, once all traces of water and alcohol are removed, the sample can be impregnated with paraffin wax. Finally, the waxed sample must be put into a microtome, which shaves parts of the sample off into thin slices capable of being examined under the microscope. Those slices then get placed upon a glass slide.

These processes are now capable of being performed via programmable, automated systems.[1]

Staining

As in cytopathology, staining involves "washing" the slide in several staining agents to better detect cells that would otherwise remain invisible to the eye when viewed under a microscope. However, most staining agents are water-based. As you can deduce from the previous steps, paraffin wax doesn't allow water absorption, and thus the wax covering the sample must be cleared. Histopathologists will in this case work backwards from the previous steps, applying several coats of xylene until the slide-prepared tissue is transparent and wax-free. That's followed up by several applications of alcohol to remove the xylene, which does not mix with water.

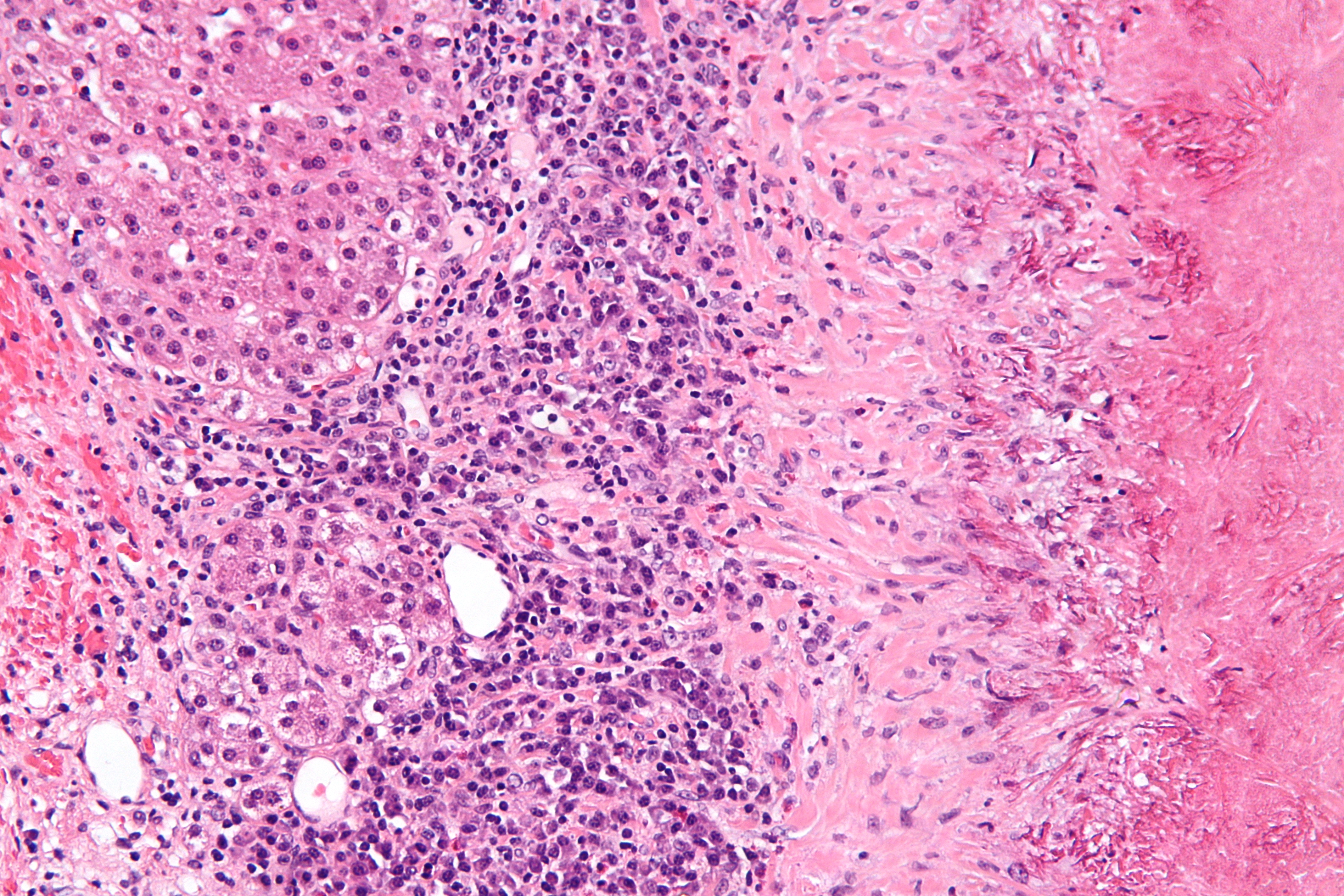

Now the tissue can be stained. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain is always the primary stain used, though additional stains may be applied afterwards. H&E has the benefit of dyeing cell nuclei blue and other structures in shades of pink, giving enough visual information to make a diagnosis. In cases where even more visual distinction is needed, other stains like Gram are needed to make bacteria or other structures more visible. Finally, a coverslip is placed over the preparation to ensure optimal flatness for examination.[1]

Examination

The common technique a trained pathologist or clinical technician will use to examine a histopathologic preparation is by bright-field microscopy. If prepared properly, the components of the sample should appear properly under microscopic view. In some cases, other optical systems may be required to better view the sample. Fluorescence microscopy (detects autofluorescent molecules), confocal scanning microscopy (view tissue in three dimensions), and electron microscopy (view tissue at high resolution) may all be applied in examining specific non-standard samples.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Evans, David; Robinson, Max; Orchard, Guy (ed.); Nation, Brian (ed.) (2011). "Chapter 1: What is Histopathology?". Histopathology. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–33. ISBN 9780199574346. http://books.google.com/books?id=qWScAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA3. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ "Rudolf Virchow — father of cellular pathology". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 86 (12): 688–689. December 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1294355/?page=1. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ Virchow, Rudolf Ludwig Karl (1860). Cellular Pathology as Based Upon Physiological and Pathological Histology. John Churchill. http://books.google.com/books?id=nmEGHJy9uswC&printsec=frontcover. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ↑ Bignold, Leon P.; Coghlan, Brian L. D.; Jersmann, Hubertus P.A. (2007). David Paul von Hansemann: Contributions to Oncology: Context, Comments and Translations. Springer. p. xii. ISBN 9783764377694. http://books.google.com/books?id=i2fEpOXxgvkC&pg=PR12&lpg=PR12. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ Edmundson, Walter F. (February 1948). "Microscopic Grading of Cancer and Its Practical Implication". Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology 57 (2): 141–150. doi:10.1001/archderm.1948.01520140003001. http://archderm.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=521834. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ Ross, Michael H.; Pawlina, Wojciech (2006). "Chapter 1: Methods - Microscopy". Histology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 12–22. ISBN 9780781767903. http://books.google.com/books?id=FoSiGTXn6BUC&pg=PA12. Retrieved 23 April 2014.