Journal:Effect of good clinical laboratory practices (GCLP) quality training on knowledge, attitude, and practice among laboratory professionals: Quasi-experimental study

| Full article title | Effect of good clinical laboratory practices (GCLP) quality training on knowledge, attitude, and practice among laboratory professionals: Quasi-experimental study |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research |

| Author(s) | Patel, Seema; Garima, Gini; Bhatia, Sonam; Latha, Thammineni K.; Thakur, Nidhi; Pujani, Mukta; Sharma, Suman B. |

| Author affiliation(s) | ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Sidda Ganga Medical College and Research Institute, Amrita School of Medicine |

| Primary contact | t dot krishnalatha at gmail dot com |

| Year published | 2023 |

| Volume and issue | 17(9) |

| Page(s) | BC05 - BC09 |

| DOI | 10.7860/JCDR/2023/62492.18453 |

| ISSN | 0973-709X |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.jcdr.net//article_fulltext.asp |

| Download | https://www.jcdr.net/articles/PDF/18453/ (PDF) |

Abstract

Introduction: Good clinical laboratory practices (GCLP) play a vital role in early and accurate diagnosis, providing high-quality data and timely sample processing. Adhering to a robust quality management system (QMS) that complies with GCLP standards is crucial for laboratory personnel in a clinical laboratory to deliver outstanding healthcare services and reliable, reproducible reports.

Aim: To assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of laboratory professionals towards quality in the laboratory through GCLP training.

Materials and methods: This pre-test, post-test quasi-experimental study was conducted in the Department of Biochemistry at Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad, Haryana, India, from February 2022 to June 2022. The study included 58 participants, consisting of 22 doctors and the remaining laboratory assistants. The GCLP online training program was conducted every Friday in March 2022 for four weeks. An online questionnaire containing 34 questions was administered to all the participants before and after the training. Data were collected and analyzed using a paired t-test.

Results: A total of 58 responses were received from the participants via Google form before and after the training. The results indicate no significant difference in participants’ responses to 12 closed-ended questions regarding a QMS before and after training. A similar trend was observed for 22 questions on a Likert scale, where participants rated their agreement, neutrality, or disagreement.

Conclusion: The study demonstrates that all technical staff fully complied with GCLP guidelines and accreditation requirements. Furthermore, the laboratory staff acknowledged the importance of standard operating procedures (SOPs), document maintenance, record-keeping, and identifying non-conformities, all of which contribute to effective traceability of the testing process in the clinical laboratory.

Keywords: clinical laboratory assistants, good clinical laboratory practices, quality assurance, quality control, standard operating procedures

Introduction

Clinical laboratories are an indispensable part of healthcare services as they provide test results crucial for decision-making by physicians and clinicians in the screening, diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of disease.[1][2][3] The quality of reports generated by laboratory personnel significantly impacts patient outcomes and treatment. Errors in any of the three phases (pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical) of analysis can have disastrous consequences for patient care.[4] Therefore, it is essential for laboratorians to have a comprehensive understanding of quality systems, as laboratorians are the first point of contact in sample handling and test procedures.

To provide reliable and reproducible results for outstanding healthcare services, laboratory personnel must adhere to a robust quality management system (QMS) that complies with good clinical laboratory practice (GCLP) standards.[5] Currently, there are multiple standards available to guide laboratorians on quality control (QC), quality assurance (QA), and QMSs. Well-known organizations such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)[6] and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)[7] establish standards and guidelines for laboratory quality. Additionally, organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), and Division of AIDS (DAIDS) provide guidelines for improving laboratory quality from time to time.

Good laboratory practices (GLPs) are a set of principles that define a quality system concerning the organizational process and conditions under which laboratory studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, archived, and reported.[8] GCLP is based on the implementation of GLP principles for the analysis of clinical samples. GCLP focuses on key aspects of a quality system, including QC, assay validation, laboratory safety, sample management, records management, proficiency testing programs, laboratory information systems (LIS), overall quality management plans, and training of laboratory personnel. Implementing GCLP ensures the generation of high-quality data along with timely sample processing, enabling early and accurate diagnosis, in turn leading to desired clinical outcomes. To protect patient safety and ensure data reliability, it is vital to avoid GCLP breaches by executing integrated, harmonized operations and establishing an effective laboratory QMS.[9]

Clinical laboratories and laboratory personnel have an ethical obligation to provide accurate and precise results that are cost- and time-effective, necessitating strict adherence to quality planning. Quality planning includes standardizing laboratory processes, QC, QA, and continual quality improvement (CQI).[5][10] Training plays a key role in ensuring correct implementation of guidelines and achieving quality output at all levels of laboratory personnel.[11] Furthermore, laboratorians need to have good knowledge and a positive attitude towards QA, which can be achieved through training on GCLP for QA implementation.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) towards quality in the laboratory through GCLP training, as the quality system depends on the skills, knowledge, commitment, and continuous practice of laboratory personnel.

Materials and methods

A pre-test, post-test quasi-experimental study was conducted in the Department of Biochemistry at Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC) Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad, Haryana, India, from February 2022 to June 2022. The study was conducted after obtaining ethical clearance from the institutional ethics committee (Ref No: 134 X/11/13/2022-IEC/12), and all participants provided verbal consent for the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A total of 58 college and hospital staff who enrolled for GCLP training were included in the study. Participants unwilling to participate or who did not attend the GCLP training were excluded.

Sample size

In this study, 58 participants were enrolled, including 22 doctors and the remaining laboratory assistants from four departments (Department of Biochemistry, Pathology and Microbiology, Immunohaematology, and Blood Transfusion) of ESIC Medical College and Hospital. Samples were chosen using a non-probability convenience sampling method since the study was based on an online questionnaire.

Procedure

Data collection

The GCLP online training program was organized by the Clinical Development Services Agency (CDSA) and the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute (THSTI) in collaboration with the ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad. The training took place every Friday in March 2022 for a period of four weeks. Eminent experts and experienced trainers from CDSA and THSTI conducted the online training from 1:30 PM to 5:00 PM. The training program consisted of four modules covering GCLP guidelines, infrastructure, organization, personnel, equipment, reagents, examination processes, pre- and post-examination processes, ethical considerations, internal QC, external assessment/proficiency testing, quality management, risk management, quality indicators, test method validation, verification, safety in laboratories, data management, LISs, internal audits, and GCLP dos and don’ts. Participants who successfully completed the program and met the administrative requirements—including attendance, feedback, and a minimum score on the exit assessment—were awarded a certificate. The training module was prepared by THSTI in collaboration with ESIC Medical College and Hospital, referring to GCLP guidelines.[12] Each session started with a recap of the previous session presented by randomly chosen participants. An exit assessment, conducted as a proctored online exam by THSTI, Faridabad, was administered after the completion of the four modules.

The questionnaire was explained to all participants, including the types of questions (Yes/No, Likert Scale: agree 1/neutral 2/disagree 3), the mode of answering, and the deadline for submission. Anonymity of responses was maintained throughout the study. The questionnaire consisted of 34 questions, including 12 closed-ended questions with predefined options and 22 questions regarding participants’ opinions on accreditation, internal quality control (IQC), external quality assessment schemes (EQASs), QMSs, etc. A pilot study was conducted with a group of 10 senior faculty members from the departments of Biochemistry, Pathology, and Microbiology to test the online questionnaire, and it was modified accordingly. The reliability score, calculated using Cronbach’s alpha test, was found to be 0.99. Participants included in the pilot study were excluded from the main study. The revised questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire was distributed electronically to all participants using Google Forms. The same questionnaire was distributed to participants before and after GCLP training, and data were collected.

Questionnaire

A pre-designed questionnaire in the English language was used in the study, based on previous studies.[11][13] The questionnaire was distributed electronically using Google Forms, with a link sent to all participants. The participants were given 660 minutes to fill out the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 34 questions, of which 22 were analyzed using a Likert scale of 1-3 to indicate the participants’ level of agreement (1: agreement, 2: neutral, 3: disagreement). The remaining 12 questions were closed-ended with predefined options. Mean scores were calculated from the responses, where a mean score <2 indicated agreement and a mean score >2 indicated disagreement.

Statistical analysis

Completed responses were exported to Microsoft Excel 2016. Continuous measurements were presented as Mean±SD, including the 22 responses on the Likert scale. Categorical measurements were presented as percentages. A multiple comparison test was conducted to compare the questionnaire responses before and after GCLP training. The paired t-test was used to determine the significance of study parameters on both continuous and categorical scales. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad version 07 software. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In the present study, the mean age of the study population was 33±5.3 years. Of the respondents, 59.3% were male and 40.7% were female.

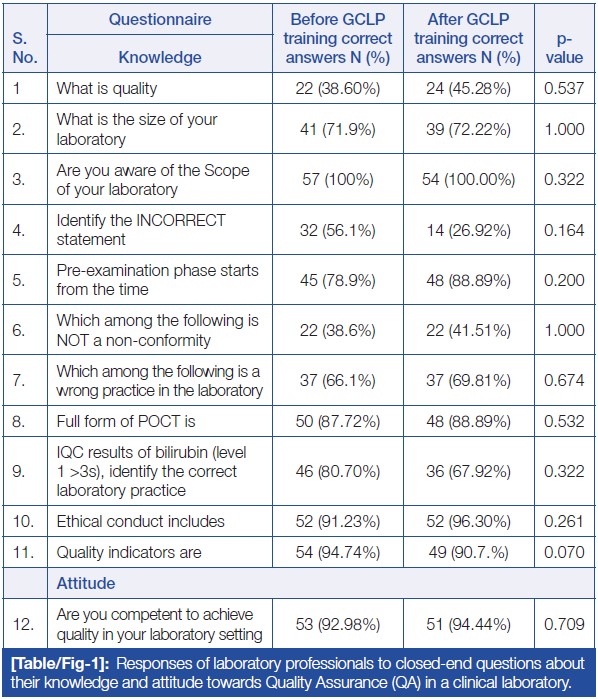

Table/Figure 1 represents the participants’ responses to closed-ended questions regarding their knowledge and attitude towards GCLP quality. The questions consisted of 12 statements, with 11 related to knowledge and one related to attitude. Ten statements had multiple options, requiring participants to choose the correct option, while two questions (Q3: Are you aware of the Scope of your laboratory? and Q12: Are you competent to achieve quality in your laboratory setting?) were of a Yes/No type. The data showed no statistically significant difference in the responses of participants regarding knowledge and attitude before and after GCLP training.

|

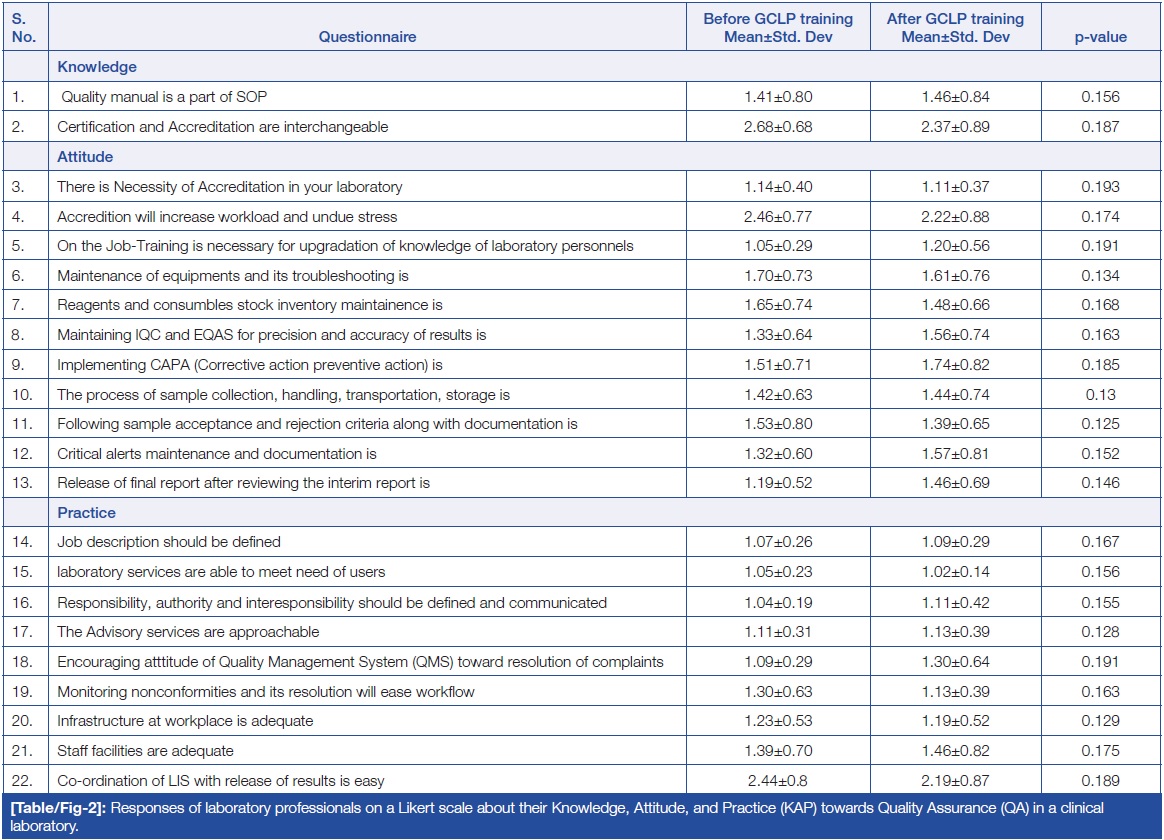

Table/Figure 2 summarizes the responses from study participants using a three-point Likert scale. This section included 22 questions that assessed participants’ opinions on accreditation, IQC, EQAS, QMS, and other related topics. Among the 22 statements, two questions assessed knowledge, 11 questions assessed attitude, and nine questions assessed practice. Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement related to laboratory quality. The data were presented as Mean±SD (standard deviation). The findings indicated no statistically significant difference in the responses of participants regarding the KAP before and after GCLP training.

Regarding attitude, three out of the 11 statements had responses of agree, disagree, and neutral, while the remaining eight statements were related to easiness, difficulty, or neutrality.

|

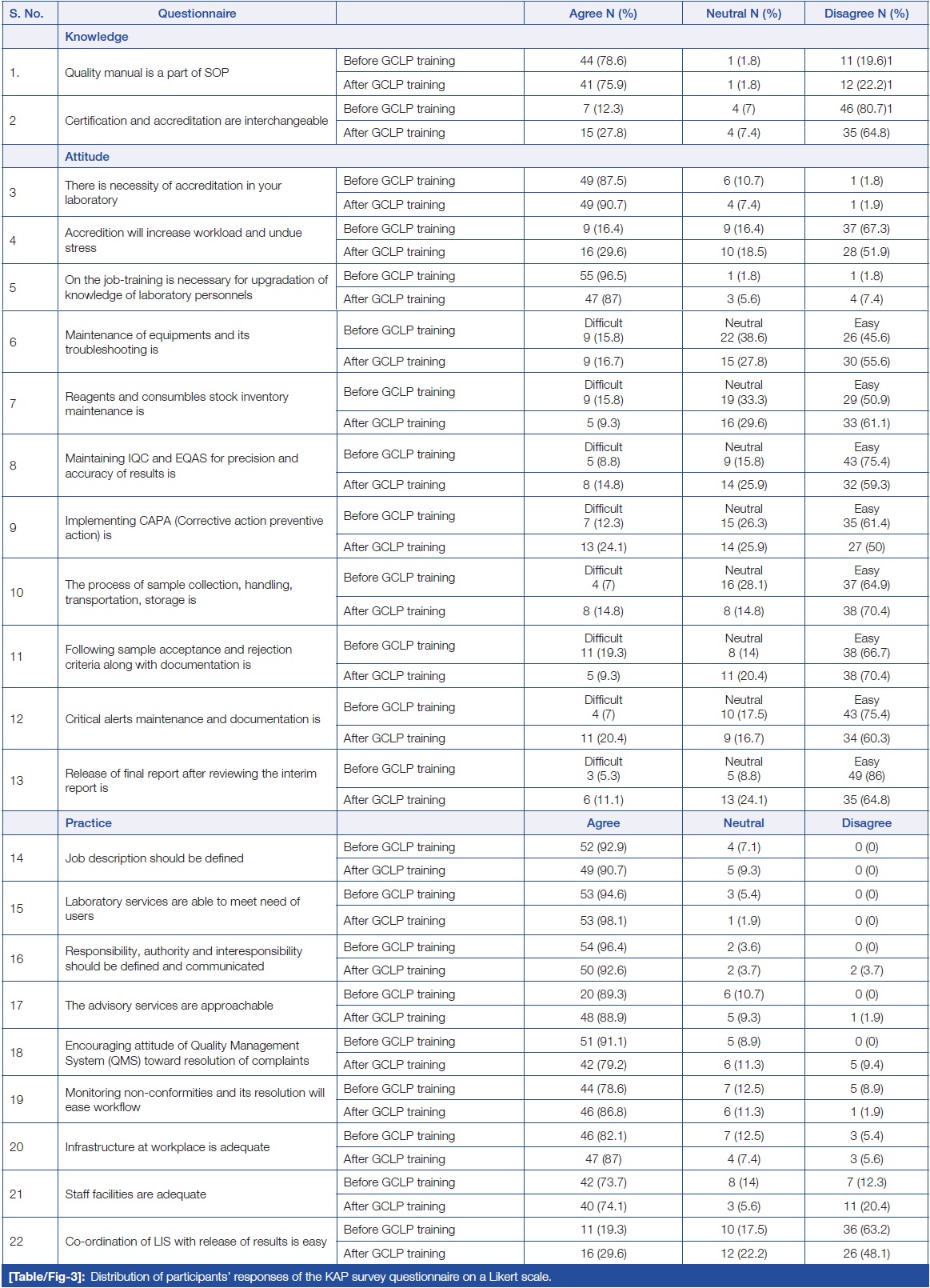

Table/Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of responses from study participants using a three-point Likert scale. In terms of attitude, when participants were asked about the necessity of accreditation in their laboratory, no difference was found in the responses before and after GCLP training. Similarly, in terms of practice, when respondents were asked if laboratory services were able to meet the needs of users, an equal number of respondents agreed, and no difference was found in the responses before and after GCLP training.

|

Overall, the study results suggest that there were no significant differences in participants’ knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding GCLP quality before and after GCLP training.

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the knowledge, practice, and attitude (KAP) of laboratory professionals towards laboratory quality training using an online questionnaire. The study was conducted amongst laboratory professionals in the Clinical Laboratory at ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad. Participants were asked questions related to QA to assess their KAP. The same questionnaire was administered before and after GCLP training, and the responses were compared.

"Knowledge," defined here as the understanding of laboratory professionals regarding QA principles, was analyzed based on participants’ agreement with statements about laboratory QA.[13] Interestingly, the data showed no statistically significant difference in the responses of participants regarding KAP before and after GCLP training. A similar study conducted in Vermont, United States, also reported high knowledge levels among laboratory staff, with 85% of the staff being oriented in QA guidelines.[4]

"Attitude" refers to the perception of laboratory professionals regarding the significance of QA, while "practice" refers to their inclination to follow and comply with laboratory QA procedures.[13] The results indicated no statistically significant difference in participants’ responses regarding attitude and practice before and after GCLP training. The study revealed that the working staff was well aware of the importance of GCLP and recognized the impact of quality on results, despite the additional workload associated with maintaining NABL/ISO standards. The consistent adherence to standard operating procedures (SOPs) and maintenance of QC records demonstrated the competence of laboratory professionals, which played a significant role in the timely processing and reporting of samples in the clinical laboratory.

A recent study conducted in Croatia amongst employees of accredited medical laboratories reported a positive attitude towards accreditation and an existing awareness of its benefits. However, the study also highlighted concern such as lack of familiarity with accreditation requirements and insufficient information on new operating procedures and working instructions. These findings emphasize the need for establishing systems to ensure timely and accurate downstream information flow for full compliance with accreditation requirements and working protocols.

Correspondingly, a study conducted in Lahore, Pakistan regarding the knowledge level of their medical lab technologists (MLTs) on QC stated that 76% of their MLTs had average knowledge and 10% had good knowledge.[14] An Ethiopian study of 175 participants has reported that 81.7% of respondents had a better knowledge on internal QC.[15] On the contrary, a Chennai-based Indian study of 10 laboratory staff reported a lapse in basic knowledge of laboratory staff on external QA, though their knowledge levels were improved after the training.[16] Previous studies reported that increased workload for maintaining records like CAPA, QC, LJ charts, etc., require long-term time commitment and were perceived as a disadvantage of accreditation.[17]

The current study clearly indicates that all laboratory professionals acknowledge the importance of well-organized workflows, SOPs, document maintenance, records, and identifying non-conformities, which collectively contribute to the effective traceability of the testing process in the clinical laboratory.

Limitations

The online nature of the GCLP training due to the ongoing Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may have differed from more traditional onsite training. Additionally, the assessment relied on subjective responses, potentially introducing response bias. Future plans should include onsite training to enhance knowledge and technical expertise among laboratory professionals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate no statistically significant differences in perceptions and attitudes of laboratory staff towards quality after GCLP training. The study emphasizes that all technical staff fully comply with GCLP guidelines and accreditation requirements. Furthermore, the findings suggest a positive attitude towards GCLP guidelines and accreditation, with laboratory staff being well aware of the benefits they offer. However, frequent training and competence assessments of laboratory professionals are necessary to enhance their technical expertise in accordance with regulatory bodies’ requirements. Such training and assessments would also aid in evaluating the performance of laboratory staff, contributing to improved learning, execution of GLPs, and consistent patient care services.

Abbreviations, acronyms, and initialisms

- CDSA: Clinical Development Services Agency

- CLSI: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019

- CQI: continual quality improvement

- DAIDS: Division of AIDS

- EQAS: external quality assessment scheme

- ESIC: Employees’ State Insurance Corporation

- GCLP: good clinical laboratory practice

- GLP: good laboratory practice

- ICMR: Indian Council of Medical Research

- IQC: internal quality control

- ISO: International Organization for Standardization

- KAP: knowledge, practice, and attitude

- LIS: laboratory information system

- MLT: medical lab technologist

- QA: quality assurance

- QC: quality control

- QMS: quality management system

- SOP: standard operating procedure

- THSTI: Translational Health Science and Technology Institute

- WHO: World Health Organization

Acknowledgements

The authors here would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Suchetha Banerjee Kurundkar and her team from the Clinical Development Services Agency, Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, for organizing and collaborating with ESIC MCH, Faridabad in conducting the online GCLP training program. Your support and expertise were instrumental in the successful implementation of the training program and the completion of this study. The authors appreciate your dedication to promoting quality laboratory practices and improving the knowledge and skills of laboratory professionals. Thank you once again for your invaluable contribution.

Ethics

- Was ethics committee approval obtained for this study? Yes

- Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

Competing interests

Financial or other competing interests: None

References

- ↑ Gershy-Damet, Guy-Michel; Rotz, Philip; Cross, David; Belabbes, El Hadj; Cham, Fatim; Ndihokubwayo, Jean-Bosco; Fine, Glen; Zeh, Clement et al. (1 September 2010). "The World Health Organization African Region Laboratory Accreditation Process" (in en). American Journal of Clinical Pathology 134 (3): 393–400. doi:10.1309/AJCPTUUC2V1WJQBM. ISSN 1943-7722. https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article/134/3/393/1766200.

- ↑ Martin, Robert; Hearn, Thomas L; Ridderhof, John C; Demby, Austin (1 May 2005). "Implementation of a quality systems approach for laboratory practice in resource-constrained countries" (in en). AIDS 19 (Supplement 2): S59–S65. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000172878.20628.a8. ISSN 0269-9370. https://journals.lww.com/00002030-200505002-00008.

- ↑ Wians, Frank H. (1 February 2009). "Clinical Laboratory Tests: Which, Why, and What Do The Results Mean?". Laboratory Medicine 40 (2): 105–113. doi:10.1309/LM404L0HHUTWWUDD. ISSN 0007-5027. http://labmedicine.metapress.com/openurl.asp?genre=article&id=doi:10.1309/LM404L0HHUTWWUDD.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Blumen, Steven R.; Naud, Shelly; Palumbo, Mary Val; McIntosh, Barbara; Wilcke, Burton W. (1 May 2010). "Knowledge and Perceptions of Quality Systems among Vermont Laboratorians" (in en). Public Health Reports 125 (2_suppl): 73–80. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S209. ISSN 0033-3549. PMC PMC2846805. PMID 20518447. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00333549101250S209.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gumba, Horace; Waichungo, Joseph; Lowe, Brett; Mwanzu, Alfred; Musyimi, Robert; Thitiri, Johnstone; Tigoi, Caroline; Kamui, Martin et al. (25 June 2019). "Implementing a quality management system using good clinical laboratory practice guidelines at KEMRI-CMR to support medical research" (in en). Wellcome Open Research 3: 137. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14860.2. ISSN 2398-502X. PMC PMC6305232. PMID 30607370. https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/3-137/v2.

- ↑ "ISO Search - laboratory quality". International Organization for Standardization. 2023. https://www.iso.org/search.html?qt=&sea+rchSubmit=Search&sort=rel&type=simple&published=true&q=laboratory+quality.

- ↑ "Quality Management Systems | Standards". Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2023. https://clsi.org/standards/products/quality-management-systems/.

- ↑ Stevens, W. (1 April 2003). "Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP): The Need for a Hybrid of Good Laboratory Practice and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines/Standards for Medical Testing Laboratories Conducting Clinical Trials in Developing Countries" (in en). Quality Assurance 10 (2): 83–89. doi:10.1080/10529410390262727. ISSN 1052-9411. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10529410390262727.

- ↑ Nkengasong, John N. (1 September 2010). "A Shifting Paradigm in Strengthening Laboratory Health Systems for Global Health: Acting Now, Acting Collectively, but Acting Differently" (in en). American Journal of Clinical Pathology 134 (3): 359–360. doi:10.1309/AJCPY5ASUEJYQ5RK. ISSN 0002-9173. https://academic.oup.com/ajcp/article-lookup/doi/10.1309/AJCPY5ASUEJYQ5RK.

- ↑ Mao, Xuehui; Shao, Jing; Zhang, Bingchang; Wang, Yong (15 June 2018). "Evaluating analytical quality in clinical biochemistry laboratory using Six Sigma" (in en). Biochemia Medica 28 (2): 020904. doi:10.11613/BM.2018.020904. ISSN 1330-0962. PMC PMC6039163. PMID 30022890. http://www.biochemia-medica.com/en/journal/28/2/10.11613/BM.2018.020904.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ivić, Matea; Alpeza Viman, Ines; Đerek, Lovorka; Kardum Paro, Mirjana Mariana; Tomičević, Marina; Rogić, Dunja; Lapić, Ivana (15 June 2021). "Laboratory professionals’ attitudes towards ISO 15189 2012 accreditation: an anonymous survey of three Croatian accredited medical laboratories". Biochemia medica 31 (2): 331–341. doi:10.11613/BM.2021.020712. PMC PMC8183115. PMID 34140835. https://www.biochemia-medica.com/en/journal/31/2/10.11613/BM.2021.020712.

- ↑ Todd, Christopher A.; Sanchez, Ana M.; Garcia, Ambrosia; Denny, Thomas N.; Sarzotti-Kelsoe, Marcella (1 July 2014). "Implementation of Good Clinical Laboratory Practice (GCLP) guidelines within the External Quality Assurance Program Oversight Laboratory (EQAPOL)" (in en). Journal of Immunological Methods 409: 91–98. doi:10.1016/j.jim.2013.09.012. PMC PMC4136974. PMID 24120573. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022175913002688.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Arada, M.C.G.; Caduco, D.D.D.; Cho, I. et al. (2021). "Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices on Laboratory Quality Assurance among Medical Technologists in Selected Level III Hospitals in Davao City". International Journal of Progressive Research in Science and Engineering 2 (8): 398–427. https://journal.ijprse.com/index.php/ijprse/article/view/391.

- ↑ Azhar, K.; Mumtaz, A.; Ibrahim, M. et al. (2012). "Quality Assurance Among MLTs". Physicians Academy 6 (2): 17–22. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265185536_Knowledge_Attitude_and_Practice_of_Quality_Assurance_Among_Medical_Laboratory_Technologists_Working_in_Laboratories_of_Lahore.

- ↑ Dereje, M.G.; Yamirot, M.D.; Kumera, T.K. et al. (2018). "Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices of Medical Laboratory Professionals on the Use of Internal Quality Control for Laboratory Tests among Selected Health Centers in Addis Ababa Ethiopia". Primary Health Care 8 (2): 1000295. doi:10.4172/2167-1079.1000295. https://www.iomcworld.org/open-access/assessment-of-knowledge-attitude-and-practices-of-medical-laboratory-professionals-on-the-use-of-internal-quality-contro-47194.html.

- ↑ Senthilkumaran, S.; Dr. Synthia, A.; Sundhararajan, A. (2014). "A study on Awareness and knowledge about external quality assurance among clinical Biochemistry laboratory technicians in a tertiary care hospital". WebmedCentral Clinical Biochemistry 5 (9): WMC004702. doi:10.9754/journal.wmc.2014.004702. https://www.webmedcentral.com/article_view/4702.

- ↑ Lulie, Adino D.; Hiwotu, Tilahun M.; Mulugeta, Achamyeleh; Kedebe, Adisu; Asrat, Habtamu; Abebe, Abnet; Yenealem, Dereje; Abose, Ebise et al. (16 September 2014). "Perceptions and attitudes toward SLMTA amongst laboratory and hospital professionals in Ethiopia". African Journal of Laboratory Medicine 3 (2): 6 pages. doi:10.4102/ajlm.v3i2.233. ISSN 2225-2010. PMC PMC5637786. PMID 29043195. http://ajlmonline.org/index.php/ajlm/article/view/233.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with changes to presentation, spelling, and grammar as needed. The PMCID and DOI were added when they were missing from the original reference. No other changes were made in accordance with the "NoDerivatives" portion of the content license.