Difference between revisions of "Journal:Development of a core competency framework for clinical informatics"

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) (Saving and adding more.) |

Shawndouglas (talk | contribs) (Saving and adding more.) |

||

| Line 214: | Line 214: | ||

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

Three participants made reference to the fact that AI and [[machine learning]] only receive a nominal mention: | |||

<blockquote>... there’s a very nominal mention of, sort of, AI in there. I think, machine learning could be stronger, in the frameworks, I think, it’s something that people might be expected to start to look at in the clinical informatics kind of role. – P5</blockquote> | |||

'''The target level''' | |||

As the framework was intended to list the core competencies grouped by domain only, none of the versions of the framework presented were stratified into different levels of competence. Thirteen participants discussed the level or granularity of the competencies. Participants were mostly concerned that although they thought some competencies were "core," they were unsure about them being "entry level" competencies: | |||

<blockquote>I wasn’t sure whether 1.4 [health administration and services] a, b, or c, at an entry level needed to be. I think they do need to be as someone progresses as a clinical informatician but they struck me as the sort of things that you wouldn’t say examine a nurse who was newly qualified or even a newly qualified doctor or a biomedical scientist, for that matter. – P1</blockquote> | |||

Three participants specifically identified the "leadership and management" competency as one that was particularly affected by level. One participant pointed out that clinical informaticians may need to cultivate leadership and management skills at an earlier career point, due to the nature and novelty of the role: | |||

<blockquote>... some of the informaticians that we’ve worked with have actually said ... that those sort of leadership skills actually are, you know, needed more rapidly than anticipated. Because, they’re thrown into quite, sometimes quite high-level meetings ... and from that sense they can also have quite a bit of influence, maybe, with some quite big decisions sometimes. – P5</blockquote> | |||

'''Representation of a "core" competency''' | |||

Whether or not participants thought a competency was core or not seemed to depend on their role and experience showing the variety of work and experiences of informaticians: | |||

<blockquote>If you look at all of them they’re not for every clinician; some clinicians have more inclination towards using some of them than others. So the current seven [domains], if you look at it in detail, they go way beyond what would be called for all of us. – P7</blockquote> | |||

Seven participants agreed that all or most of the competencies presented were "core" and that it was not necessary to be an expert in them all, but rather to have at least an understanding or awareness of them: | |||

<blockquote>It could be unfair for us to expect people to be experts across all of those domains ... so I think the core competencies have to have an understanding that, yes, you should have a basic understanding across all of these domains but we don’t expect you to be an expert in all of them. – P12</blockquote> | |||

====Application of the framework and impact on the profession==== | |||

For this section, we applied framework analysis to examine themes surrounding the intended application of the framework, impact on the profession, and barriers. Several participants indicated an interest in how the framework might be applied and how people might meet the competencies: | |||

<blockquote>P12: So there needs to be some line that we need to meet and the core competencies should be that, but we just need to be sensitive about how we’re ensuring our members are meeting the competencies. | |||

Interviewer: It sounds like you’re saying a light touch is preferable. | |||

P12: Yeah. We don’t want to beat them with an exam stick, you know. These people are already professionals, so we need to, I don’t know, acknowledge the fact that they are already professionals within their own right and experts in their own right and this is an additional bit and not scare them off by putting them through hours and hours of examinations or whatever.</blockquote> | |||

Another mentioned how this could be used to provide flexible portfolio training routes for clinicians and other healthcare practitioners: | |||

<blockquote>Now what’s interesting is that within that portfolio route there’s no underpinning framework, or nothing anywhere near as detailed as this. And, I think, this would be a really useful competency framework that might underpin flexible portfolio training routes for physicians. Nurses are also starting to come through and people that want to take time out of their regular day job to also diversify into, sort of, informatics type roles – P5</blockquote> | |||

Participants pointed out that some practitioners work more or less in a single competency domain or domains: | |||

<blockquote>I mean some people, their job description will purely be one domain because that’s where they will fit. I was trying to think of a CCIO. There’s probably a CIO in an organization, would this description apply to someone’s job, and I think to be fair, it’s a fairly good description of what you would expect someone to have to have to do that role. – P3</blockquote> | |||

Some barriers were also identified; one from the perspective of those involved in social care work, which seemed to work in two directions: | |||

<blockquote>P2: I think the barriers, certainly from a social care perspective, are the fact that you have to be a registered clinician, and there is no registration process for most people working within social care ... the vast majority of people that work in social care are professionals without a professional registration. | |||

Interviewer: It also sounded to me like there was actually a barrier coming from the other direction as well, with people from social care actually doing these roles, but not identifying as such? | |||

P2: Hundred percent, yeah, 100 percent. There are people in social care, who, if they were in an NHS trust, would have CCIO, CNIO responsibilities, but they do not have them in social care, because the sector does not recognize that as a role yet. So, it’s a two-way barrier, it’s not a one-way barrier at all.</blockquote> | |||

It was generally felt that the framework should be open to as many professional groups as possible, the caveat being that they should also have a clinical role. It was felt that there was a greater distinction between bioinformatics and the other types of health informatics. Some participants suggested that in the future, pathways to becoming clinical informaticians may change. Currently, those with medical/clinical training acquire informatics skills subsequently, but future pathways may involve information technology (IT) and chief information officers acquiring clinical knowledge: | |||

<blockquote>... people who are getting up to be heads of IT, chief information officers as opposed to chief clinical information officers, could probably start to pick up the levels of clinical knowledge to be a clinical informatician so long as it’s not about the clinical interpretation ... – P1</blockquote> | |||

Revision as of 21:40, 13 August 2021

| Full article title | Development of a core competency framework for clinical informatics |

|---|---|

| Journal | BMJ Health & Care Informatics |

| Author(s) | Davies, Alan; Mueller, Julia; Hassey, Alan; Moulton, Georgina |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Manchester, University of Cambridge, The Faculty of Clinical Informatics, Health Data Research UK |

| Primary contact | alan dot davies at ucl dot ac dot uk |

| Year published | 2021 |

| Volume and issue | 28(1) |

| Article # | e100356 |

| DOI | 10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100356 |

| ISSN | 2632-1009 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International |

| Website | https://informatics.bmj.com/content/28/1/e100356 |

| Download | https://informatics.bmj.com/content/bmjhci/28/1/e100356.full.pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Objectives: Up to this point, there has not been a national core competency framework for clinical informatics in the U.K. Here we report on the final two iterations of work carried out towards the formation of a national core competency framework. This follows an initial systematic literature review of existing skills and competencies and a job listing analysis.

Methods: An iterative approach was applied to framework development. Using a mixed-methods design, we carried out semi-structured interviews with participants involved in informatics (n = 15). The framework was updated based on the interview findings and was subsequently distributed as part of a bespoke online digital survey for wider participation (n = 87). The final version of the framework is based on the findings of the survey.

Results: Over 102 people reviewed the framework as part of the interview or survey process. This led to a final core competency framework containing six primary domains with 36 subdomains containing 111 individual competencies.

Conclusions: An iterative mixed-methods approach for competency development involving the target community was appropriate for development of the competency framework. There is some contention around the depth of technical competencies required. Care is also needed to avoid professional burnout, as clinicians and healthcare practitioners already have clinical competencies to maintain. Therefore, how the framework is applied in practice and how practitioners meet the competencies requires careful consideration.

Introduction

The healthcare sector in many countries is facing increasing demand as people live longer and healthier lives.[1] The public’s expectation of healthcare is also increasing and is tempered by various financial constraints. The healthcare sector has lagged behind other sectors regarding its adoption and use of digital technology. In the U.K., the Topol review was carried out to assess how the healthcare workforce can be prepared for the digital future. The review makes many recommendations on the use of genomics technology, robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and digital medicine, including the training and education of healthcare professionals in such areas.[1] At the cutting edge of this digital upskilling of the workforce are informaticians from clinical, health, and social care disciplines.

The American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) defines clinical informatics as "the application of informatics and information technology to deliver healthcare services."[2] The U.K. Faculty of Clinical Informatics (FCI) defines a clinical informatician as someone who "uses their clinical knowledge and experience of informatics concepts, methods, and tools to promote patient and population care that is person-centred, ethical, safe, effective, efficient, timely, and equitable."[3]

As of yet there are no U.K.-based overarching competency frameworks aimed at multiple informatics disciplines. Existing frameworks tend to focus on specific domains such as nursing informatics or bioinformatics.[4] The U.K. FCI was created to provide support for clinical informaticians, including those with clinical roles in the health and social care domains applying informatics in practice. It is the intention of the FCI to provide and accredit competencies for informaticians. This includes accreditation of the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) Digital Academy program which aims to create digital leaders for the digital transformation of the NHS. The present study forms part of a program commissioned by the FCI to create a national competency framework for clinical informaticians in the U.K.

Competency describes the behaviors, characteristics, skills, attitudes, and knowledge application used to successfully achieve something. Competence therefore is the achievement of a single competency or multiple competencies. A core competency framework describes the essential set of competencies required to achieve competence in a specific area. Many competency frameworks aimed at various clinical informatics disciplines currently exist, such as the ELIXIR (European Life-science Infrastructure for Biological Information) and TIGER (Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform) frameworks for bioinformaticians and nurses. This paper reports on the methods used to generate and refine the U.K. FCI’s Core Competency Framework (CCF), which covers the core competencies required to develop clinical informaticians’ professional competencies, and to provide a process for the FCI to provide accreditation for training and education programs and individual clinical informaticians.[5]

Background

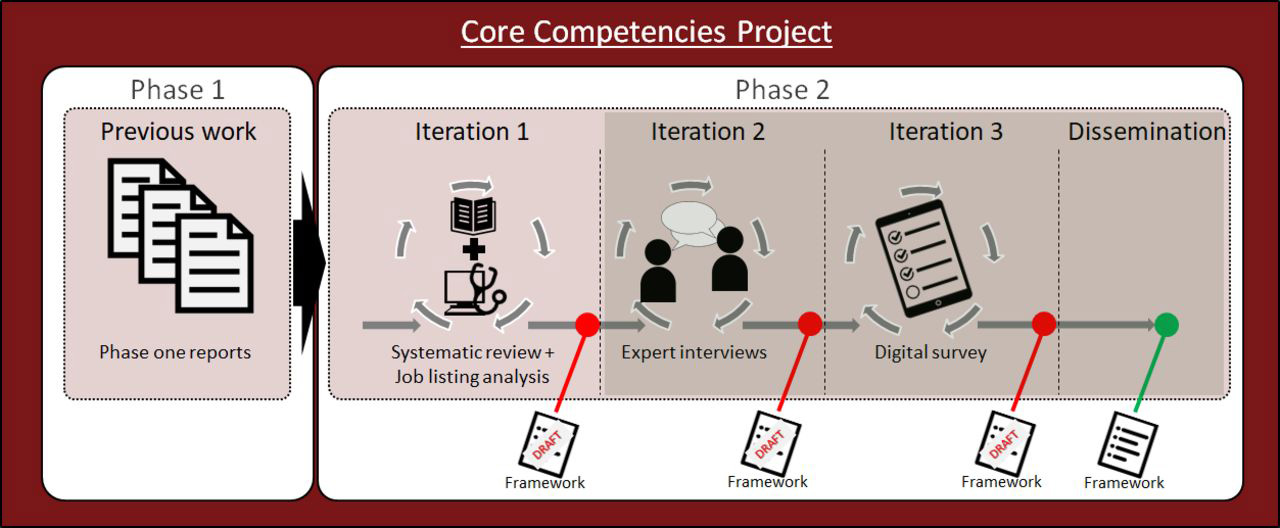

The Core Competencies Project spanned two primary phases. The first part of the work explored the definition of the professional attributes of a clinical informatician. The FCI carried out the first phase of the work (Figure 1), which consisted of three reports based on (1) discovery[6], (2) validation[7], and (3) consultation around the output competences of a clinical informatician.[3] This included defining clinical informatics, clinical informaticians, inclusivity, professional boundaries, and the functional domains (scope) of clinical informatics practice. This work was carried out using qualitative methods (e.g., interviews) with the faculty’s membership. The second phase (reported in this paper) involved an iterative process consisting of three separate iterations. The first iteration involved the combination of findings from both academia and industry in the form of an analysis of over 50 informatics job postings and a systematic literature review which explored the commonality of informatics competencies across different clinical informatics domains (such as medicine, nursing, pharmacy).[4] Following synthesis of this information, an initial draft competency framework was generated, which was then presented to 15 informatics experts in one-to-one semi-structured interviews and adapted following feedback. The amended version was presented for wider evaluation through a digital survey with 87 participants. In light of the survey results, the final version of the competency framework[5] was updated and disseminated publicly on the FCI’s website.

|

Figure 1 provides an overview of the iterative steps followed to create the final core competency framework. This paper reports on the interviews and survey (iterations 2 and 3 of phase two). The principle research questions were:

- RQ1: Was the chosen mixed-methods approach appropriate for generating a core competency framework?

- RQ2: How do participants feel the framework should be applied and to whom?

- RQ3: What competencies were considered "core" and how do they fit in with an evolving profession?

Iteration 1: Interviews

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with participants (n = 15) involved in various aspects of informatics. Participants were sent a copy of the interview schedule (see Box 2 in the supplied supplementary material) and the framework prior to the agreed interview date. Due to the COVID-19 lockdown, the interviews were carried out online using Zoom and audio recorded. Transcribed interviews were analyzed using framework analysis.[8] Framework analysis involves five stages consisting of familiarization with the data, identification of the thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping/interpretation. We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines.[9] The interview quotes were then stratified into themes by one researcher, and the quotes were independently matched to the primary themes by another. The percentage agreement between both researchers was 85.6%, with an unweighted Cohen’s kappa showing substantial agreement (κ = 0.67).

The sample

A purposive sample was obtained through the FCI, who sought to contact a wide variety of its members and associates with different professional backgrounds. Participants were from a broad set of backgrounds (Table 1). Participants were involved in informatics at various levels, from being the sole informatician in an organization through to Chief Clinical Information Officers (CCIOs) and digital leads. We omit the current roles of participants to maintain anonymity. Sectors of employment included the NHS, adult social care, and the prison system. Age and other demographic details were not requested. The clinical backgrounds were also varied and included general practice, urological surgery, pathology, and oncology. Nurses represented multiple clinical areas across their careers in both the NHS and private sector (including nursing homes).

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

Following the SRQR guidelines[9], details of the researchers' characteristics and personal attributes that may influence the research are detailed. Alan Davies (AD) has a background in computer science (PhD) and nursing science (BSc). AD works as a senior lecturer in health informatics and health data sciences and was previously a software engineer/data scientist in industry and a former cardiac nurse. AD did not personally know any of the interviewees that took part in the study, with the exception of one lecturer whom he knows in a professional capacity. AD’s research paradigm is situated in post-positivism. Julia Mueller (JM) has a background in health psychology (MSc, PhD). JM formerly worked as a lecturer in healthcare sciences teaching a course unit on digital public health, and currently works as a research associate in behavioral weight management. JM did not personally know any of the interviewees. JM’s research paradigm is situated in constructivism.

Results

A total of eight hours and 25 minutes (M = 33.66, SD = 12.28) of interview data were generated. Given the nature and topic of the interviews the results are reported in two main ways. The first set of results pertains to the required changes to the composition of the framework and to specific areas such as a specified competency. This does not require any interpretive themes and is reported descriptively. The second set of results uses framework analysis to identify themes around the potential application of the framework, who it is for, and how the participants see the informatics profession changing in the future.

Requested changes to the framework

Table 2 provides an overview of the suggested changes to the framework, broken down by topic and subtopic. This shows how many participants mentioned this topic and how many times.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Framework composition

Language and terminology

It was mentioned (n = 2) that the wording should make specific reference to "social care" rather than just "healthcare":

... you just get people looking at it, and thinking, that doesn’t apply to me. And then they never revisit it. So, it’s that first impression of appearing as welcoming as they actually are, and showing from within the competencies, that they recognize that it’s not about a job title, it’s about the roles you are doing. – P2 Social workers, the social care sector tends to notice these things, if they feel it’s too contextualized within healthcare than social care ... And you have some healthcare professionals who really lean more towards working in the community for instance. So their roles overlap much more with their social care, social work side of the system. And so it would be helpful for that to be reflected as well. – P8

Missing competency

Table 3 summarizes what participants viewed as missing competencies.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Three participants made reference to the fact that AI and machine learning only receive a nominal mention:

... there’s a very nominal mention of, sort of, AI in there. I think, machine learning could be stronger, in the frameworks, I think, it’s something that people might be expected to start to look at in the clinical informatics kind of role. – P5

The target level

As the framework was intended to list the core competencies grouped by domain only, none of the versions of the framework presented were stratified into different levels of competence. Thirteen participants discussed the level or granularity of the competencies. Participants were mostly concerned that although they thought some competencies were "core," they were unsure about them being "entry level" competencies:

I wasn’t sure whether 1.4 [health administration and services] a, b, or c, at an entry level needed to be. I think they do need to be as someone progresses as a clinical informatician but they struck me as the sort of things that you wouldn’t say examine a nurse who was newly qualified or even a newly qualified doctor or a biomedical scientist, for that matter. – P1

Three participants specifically identified the "leadership and management" competency as one that was particularly affected by level. One participant pointed out that clinical informaticians may need to cultivate leadership and management skills at an earlier career point, due to the nature and novelty of the role:

... some of the informaticians that we’ve worked with have actually said ... that those sort of leadership skills actually are, you know, needed more rapidly than anticipated. Because, they’re thrown into quite, sometimes quite high-level meetings ... and from that sense they can also have quite a bit of influence, maybe, with some quite big decisions sometimes. – P5

Representation of a "core" competency Whether or not participants thought a competency was core or not seemed to depend on their role and experience showing the variety of work and experiences of informaticians:

If you look at all of them they’re not for every clinician; some clinicians have more inclination towards using some of them than others. So the current seven [domains], if you look at it in detail, they go way beyond what would be called for all of us. – P7

Seven participants agreed that all or most of the competencies presented were "core" and that it was not necessary to be an expert in them all, but rather to have at least an understanding or awareness of them:

It could be unfair for us to expect people to be experts across all of those domains ... so I think the core competencies have to have an understanding that, yes, you should have a basic understanding across all of these domains but we don’t expect you to be an expert in all of them. – P12

Application of the framework and impact on the profession

For this section, we applied framework analysis to examine themes surrounding the intended application of the framework, impact on the profession, and barriers. Several participants indicated an interest in how the framework might be applied and how people might meet the competencies:

P12: So there needs to be some line that we need to meet and the core competencies should be that, but we just need to be sensitive about how we’re ensuring our members are meeting the competencies.

Interviewer: It sounds like you’re saying a light touch is preferable.

P12: Yeah. We don’t want to beat them with an exam stick, you know. These people are already professionals, so we need to, I don’t know, acknowledge the fact that they are already professionals within their own right and experts in their own right and this is an additional bit and not scare them off by putting them through hours and hours of examinations or whatever.

Another mentioned how this could be used to provide flexible portfolio training routes for clinicians and other healthcare practitioners:

Now what’s interesting is that within that portfolio route there’s no underpinning framework, or nothing anywhere near as detailed as this. And, I think, this would be a really useful competency framework that might underpin flexible portfolio training routes for physicians. Nurses are also starting to come through and people that want to take time out of their regular day job to also diversify into, sort of, informatics type roles – P5

Participants pointed out that some practitioners work more or less in a single competency domain or domains:

I mean some people, their job description will purely be one domain because that’s where they will fit. I was trying to think of a CCIO. There’s probably a CIO in an organization, would this description apply to someone’s job, and I think to be fair, it’s a fairly good description of what you would expect someone to have to have to do that role. – P3

Some barriers were also identified; one from the perspective of those involved in social care work, which seemed to work in two directions:

P2: I think the barriers, certainly from a social care perspective, are the fact that you have to be a registered clinician, and there is no registration process for most people working within social care ... the vast majority of people that work in social care are professionals without a professional registration.

Interviewer: It also sounded to me like there was actually a barrier coming from the other direction as well, with people from social care actually doing these roles, but not identifying as such?

P2: Hundred percent, yeah, 100 percent. There are people in social care, who, if they were in an NHS trust, would have CCIO, CNIO responsibilities, but they do not have them in social care, because the sector does not recognize that as a role yet. So, it’s a two-way barrier, it’s not a one-way barrier at all.

It was generally felt that the framework should be open to as many professional groups as possible, the caveat being that they should also have a clinical role. It was felt that there was a greater distinction between bioinformatics and the other types of health informatics. Some participants suggested that in the future, pathways to becoming clinical informaticians may change. Currently, those with medical/clinical training acquire informatics skills subsequently, but future pathways may involve information technology (IT) and chief information officers acquiring clinical knowledge:

... people who are getting up to be heads of IT, chief information officers as opposed to chief clinical information officers, could probably start to pick up the levels of clinical knowledge to be a clinical informatician so long as it’s not about the clinical interpretation ... – P1

Supplemental material

Supplementary material 1 (PDF)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Health Education England (2019). "The Topol Review – Preparing the healthcare workforce to deliver the digital future". NHS. https://topol.hee.nhs.uk/.

- ↑ American Medical Informatics Association. "Informatics: Research and Practice". American Medical Informatics Association. https://amia.org/about-amia/why-informatics/informatics-research-and-practice#:~:text=Clinical%20Informatics-,Clinical%20Informatics%20is%20the%20application%20of%20informatics%20and%20information%20technology,clinical%20informatics%20and%20operational%20informatics.&text=Clinical%20Informatics. Retrieved 02 September 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hassey, A.; Jidkov, L.; Williams, J. (2020). "Report C: Consultation stage - Consultation Exercise and Output Competences for a Clinical Informatician". Core Competencies Project - Phase 1 Final Summary Report. p. 22. https://facultyofclinicalinformatics.org.uk/core-competencies-phase1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Davies, Alan; Mueller, Julia; Moulton, Georgina (1 September 2020). "Core competencies for clinical informaticians: A systematic review". International Journal of Medical Informatics 141: 104237. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104237. ISSN 1872-8243. PMID 32771960. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32771960.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Moulton, Georgina; Davies, Alan; Mueller, Julia (22 July 2020) (in en). Protocol: Development of core competencies for Clinical Informatics in the UK. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.3956373. https://zenodo.org/record/3956373.

- ↑ Quinn, N.; Hassey, A.; Jidkov, L. (2020). "Report A: Discovery stage: Develop and Define the Professional Attributes of a Clinical Informatician – Final Report". Core Competencies Project - Phase 1 Final Summary Report. https://facultyofclinicalinformatics.org.uk/core-competencies-phase1.

- ↑ Hassey, A.; Jidkov, L.; Williams, J. (2020). "Report B: Validation stage - Validation Study and draft Output Competences for a Clinical Informatician". Core Competencies Project - Phase 1 Final Summary Report. https://facultyofclinicalinformatics.org.uk/core-competencies-phase1.

- ↑ Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. (1994). "Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research". In Bryman, A.; Burgess, B. (in English). Analyzing Qualitative Data. Routledge. pp. 173–94. ISBN 978-0-203-41308-1. OCLC 1020495928. https://www.worldcat.org/title/mediawiki/oclc/1020495928.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 O'Brien, Bridget C.; Harris, Ilene B.; Beckman, Thomas J.; Reed, Darcy A.; Cook, David A. (1 September 2014). "Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations". Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 89 (9): 1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. ISSN 1938-808X. PMID 24979285. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24979285.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. A few grammar and spelling errors were also corrected. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.