Journal:Laboratory demand management strategies: An overview

| Full article title | Laboratory demand management strategies: An overview |

|---|---|

| Journal | Diagnostics |

| Author(s) | Mrazek, Cornelia; Haschke-Becher, Elisabeth; Felder, Thomas K.; Keppel, Martin H.; Oberkofler, Hannes; Cadamuro, Janne |

| Author affiliation(s) | Paracelsus Medical University |

| Primary contact | Email: c dot mrazek at salk dot at |

| Year published | 2021 |

| Volume and issue | 11(7) |

| Article # | 1141 |

| DOI | 10.3390/diagnostics11071141 |

| ISSN | 2075-4418 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/11/7/1141/htm |

| Download | https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/11/7/1141/pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should be considered a work in progress and incomplete. Consider this article incomplete until this notice is removed. |

Abstract

Inappropriate laboratory test selection in the form of overutilization as well as underutilization, frequently occurs despite available guidelines. There is broad approval among laboratory specialists and clinicians that demand management (DM) strategies are useful tools to avoid this issue. Most of these tools are based on automated algorithms or other types of machine learning. This review summarizes the available DM strategies that may be adopted to local settings. We believe that artificial intelligence (AI) may help to further improve these available tools.

Keywords: appropriate laboratory test ordering overutilization, pre-analytical phase, underutilization

Introduction

Laboratory tests are fundamental for medical diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment decisions[1] and are being ordered in rising numbers each year due to increased availability, mostly based on technological advances.[2] However, due to this fact that laboratory orders increase along with convenient availability, it seems that a certain amount of laboratory tests are ordered inappropriately.[3][4] On the one hand, inappropriate orders may present as overutilization, where tests with doubtful contribution to further patient management are ordered; on the other hand, there may be underutilization, when required tests are not being ordered.[5] Even if studies estimating over- or underuse are rarely comparable due to differences in study design, it seems that the extent is not negligible. In a systematic review, Zhi et al.[5] estimated an overall mean rate of overutilization of 20.6%. Subgroup analysis revealed a higher mean rate, around 44%, for inappropriate initial testing. However, single studies state that up to 70% of ordered tests may be of doubtful importance for patient management.[6][7] A workup of closed malpractice claims conducted by Gandhi et al.[8], as well as Kachalia et al.[9], revealed that failure to order the appropriate diagnostic or laboratory test contributed to missed or delayed diagnoses in 55% and 58% of cases in an ambulatory setting and the emergency department, respectively. Zhi et al.[5] state the overall mean rate of underutilization is 44.8%.

Along with Sarkar et al.[10], who support the high proportions of errors in test selection by evaluating orders for coagulation disorders in real time, inappropriate ordering may be considered a substantial threat to patient safety. Overutilization may lead to unnecessary follow-up investigations or treatments, increased workload and costs, and increased patient anxiety, while underutilization may result in missed or delayed diagnoses.[5][11][12] Lack of knowledge, insecurity, pure habit, patient pressure, or fear of lawsuits are possible causes for inappropriate testing.[13][14][15] The lack of knowledge is reflected by various studies, which observed inappropriate orders despite available guidelines or recommendations on the implementation of demand management (DM) tools.[12][14][16][17][18]

This review summarizes available DM strategies, which may be implemented into local settings to reduce inappropriate test utilization.

Possible strategies to avoid inappropriate test utilization

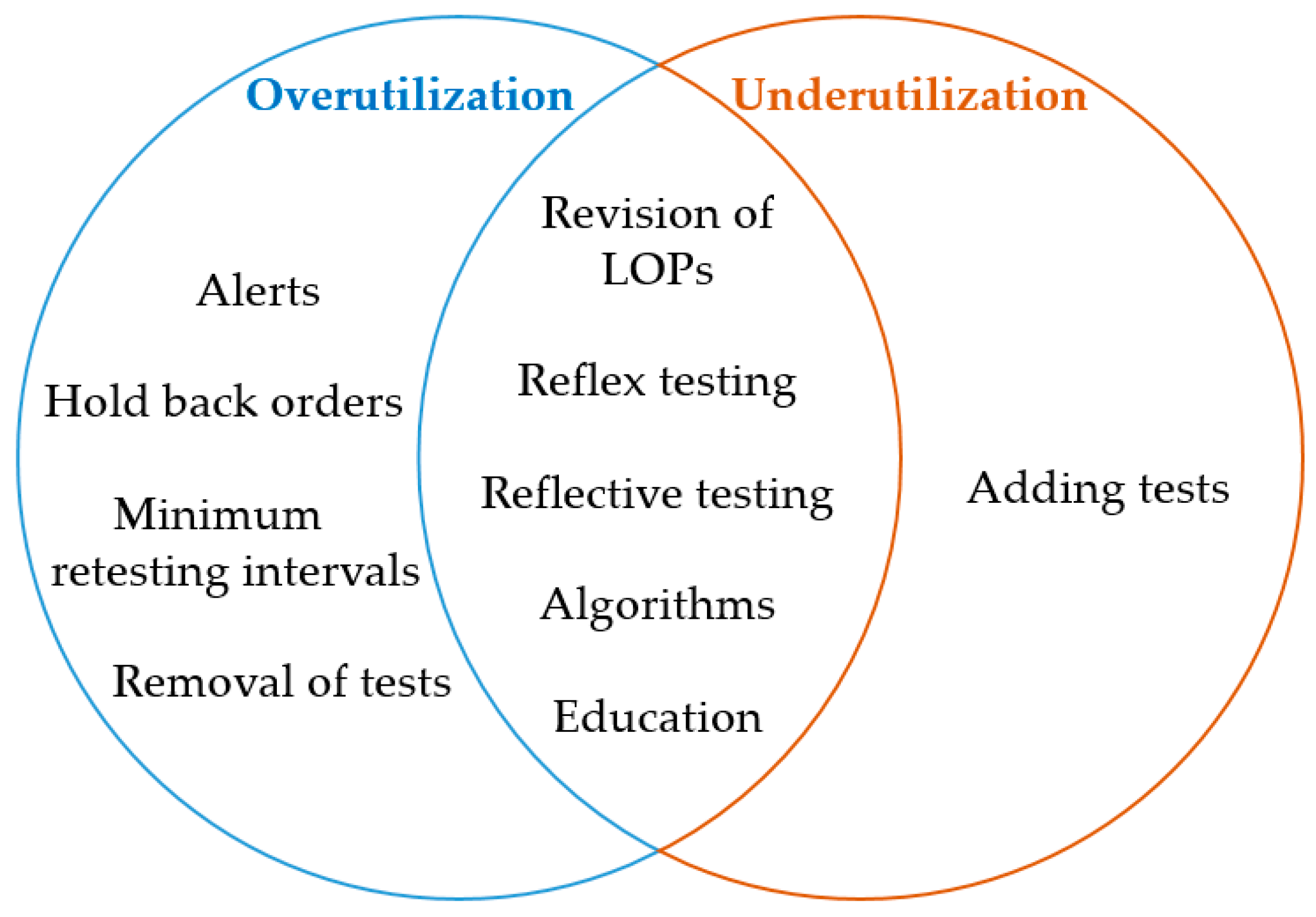

DM tools may help to prevent overutilization and underutilization. An attempt to categorize the different DM strategies as appropriate tools to overcome over- and underutilization is depicted in Figure 1.

|

Many studies combine several tools[14][17][19], which has been shown to have an additive effect on the overall outcome.[20] In addition, the collaboration of laboratory specialists and clinicians together with audits, feedback, reminders, and multiple plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles will further improve efficiency in terms of a continuous improvement process.[12][14][18][19]

Alerts at the stage of order entry

Alerts appearing in the form of pop-up windows in the clinical physician order entry (CPOE) system may be designed to avoid various causes of overutilization.

Lippi et al.[21] implemented alerts for biological implausibility concerning age (e.g., beta human chorionic gonadotropin in patients < 9 and > 60 years) or gender (e.g., prostatic specific antigen [PSA] in females) at two university hospital wards. In addition, alerts for minimum retesting intervals (MRIs) were implemented (addressed in a further subsection). The alert provides an explanation as to why the order is deemed inappropriate and enables the ordering provider to choose order cancellation or acceptance.

Similarly, Juskewitch et al.[16] implemented an alert, triggered by the concomitant order of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) in a community health system. Again, the user is informed about the inappropriate request and has the choice to cancel ESR or to proceed with the order. The implementation of this DM strategy resulted in a 42% relative rate reduction of ESR/CRP co-ordering.

Alerts may also help to suggest an alternative test, as Parkhurst et al.[22] showed. The authors reduced genetic testing of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) by informing the ordering physician about the latest recommendations of MTHFR testing, including the suggestion of homocysteine as an alternate test. In this study, the choice of overruling or adopting the suggestion was left with the user. Overall, there was a significant decrease of average monthly MTHFR tests from 12.93 per million patients in the year before the intervention to 7.08 per million patients afterwards.

Larochelle et al.[17] aimed to improve ordering of cardiac biomarkers according to guidelines for the diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). As part of a multimodal intervention, including education and several changes in the CPOE system (see later subsections), a pop-up alert was introduced, triggered by the order of creatinkinase (CK) and CK-MB isoform (CK-MB), informing the user about the recommended indications for these tests.

MRIs, which may also be implemented in the form of alerts at the stage of order entry, are discussed in the subsection about minimum retesting intervals.

Hold back orders in the laboratory information system (LIS)

References

- ↑ Whiting, Penny; Toerien, Merran; de Salis, Isabel; Sterne, Jonathan A.C.; Dieppe, Paul; Egger, Matthias; Fahey, Tom (1 October 2007). "A review identifies and classifies reasons for ordering diagnostic tests" (in en). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60 (10): 981–989. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.01.012. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0895435607000820.

- ↑ Fryer, Anthony A; Hanna, Fahmy W (1 November 2009). "Managing demand for pathology tests: financial imperative or duty of care?" (in en). Annals of Clinical Biochemistry: International Journal of Laboratory Medicine 46 (6): 435–437. doi:10.1258/acb.2009.009186. ISSN 0004-5632. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1258/acb.2009.009186.

- ↑ Blumberg, Gari; Kitai, Eliezer; Vinker, Shlomo; Golan-Cohen, Avivit (1 June 2019). "Changing electronic formats is associated with changes in number of laboratory tests ordered". The American Journal of Managed Care 25 (6): e179–e181. ISSN 1936-2692. PMID 31211550. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31211550.

- ↑ Mrazek, Cornelia; Simundic, Ana-Maria; Salinas, Maria; von Meyer, Alexander; Cornes, Michael; Bauçà, Josep Miquel; Nybo, Mads; Lippi, Giuseppe et al. (1 June 2020). "Inappropriate use of laboratory tests: How availability triggers demand – Examples across Europe" (in en). Clinica Chimica Acta 505: 100–107. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.02.017. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0009898120300723.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Zhi, Ming; Ding, Eric L.; Theisen-Toupal, Jesse; Whelan, Julia; Arnaout, Ramy (15 November 2013). Szecsi, Pal Bela. ed. "The Landscape of Inappropriate Laboratory Testing: A 15-Year Meta-Analysis" (in en). PLoS ONE 8 (11): e78962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078962. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC PMC3829815. PMID 24260139. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078962.

- ↑ Cadamuro, Janne; Gaksch, Martin; Wiedemann, Helmut; Lippi, Giuseppe; von Meyer, Alexander; Pertersmann, Astrid; Auer, Simon; Mrazek, Cornelia et al. (1 April 2018). "Are laboratory tests always needed? Frequency and causes of laboratory overuse in a hospital setting" (in en). Clinical Biochemistry 54: 85–91. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.01.024. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0009912017312274.

- ↑ Miyakis, S.; Karamanof, G.; Liontos, M.; Mountokalakis, T. D (1 December 2006). "Factors contributing to inappropriate ordering of tests in an academic medical department and the effect of an educational feedback strategy" (in en). Postgraduate Medical Journal 82 (974): 823–829. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.049551. ISSN 0032-5473. PMC PMC2653931. PMID 17148707. https://pmj.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/pgmj.2006.049551.

- ↑ Gandhi, Tejal K.; Kachalia, Allen; Thomas, Eric J.; Puopolo, Ann Louise; Yoon, Catherine; Brennan, Troyen A.; Studdert, David M. (3 October 2006). "Missed and Delayed Diagnoses in the Ambulatory Setting: A Study of Closed Malpractice Claims" (in en). Annals of Internal Medicine 145 (7): 488–96. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00006. ISSN 0003-4819. http://annals.org/article.aspx?doi=10.7326/0003-4819-145-7-200610030-00006.

- ↑ Kachalia, Allen; Gandhi, Tejal K.; Puopolo, Ann Louise; Yoon, Catherine; Thomas, Eric J.; Griffey, Richard; Brennan, Troyen A.; Studdert, David M. (1 February 2007). "Missed and delayed diagnoses in the emergency department: a study of closed malpractice claims from 4 liability insurers". Annals of Emergency Medicine 49 (2): 196–205. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.035. ISSN 1097-6760. PMID 16997424. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16997424.

- ↑ Sarkar, Mayukh K.; Botz, Chad M.; Laposata, Michael (1 March 2017). "An assessment of overutilization and underutilization of laboratory tests by expert physicians in the evaluation of patients for bleeding and thrombotic disorders in clinical context and in real time". Diagnosis (Berlin, Germany) 4 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1515/dx-2016-0042. ISSN 2194-802X. PMID 29536907. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29536907.

- ↑ Cornes, Michael (15 June 2017). "Case report of unexplained hypocalcaemia in a slightly haemolysed sample" (in en). Biochemia Medica 27 (2): 426–429. doi:10.11613/BM.2017.046. ISSN 1330-0962. PMC PMC5493164. PMID 28694734. http://www.biochemia-medica.com/en/journal/27/2/10.11613/BM.2017.046.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Whiting, Darunee; Croker, Richard; Watson, Jessica; Brogan, Andy; Walker, Alex J; Lewis, Tom (1 March 2019). "Optimising laboratory monitoring of chronic conditions in primary care: a quality improvement framework" (in en). BMJ Open Quality 8 (1): e000349. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000349. ISSN 2399-6641. PMC PMC6440689. PMID 30997410. https://qir.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000349.

- ↑ Vrijsen, B.E.L.; Naaktgeboren, C.A.; Vos, L.M.; van Solinge, W.W.; Kaasjager, H.A.H.; ten Berg, M.J. (1 March 2020). "Inappropriate laboratory testing in internal medicine inpatients: Prevalence, causes and interventions" (in en). Annals of Medicine and Surgery 51: 48–53. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2020.02.002. PMC PMC7021522. PMID 32082564. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2049080120300157.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Bartlett, Kristen J; Vo, Ann P; Rueckert, Justin; Wojewoda, Christina; Steckel, Elizabeth H; Stinnett-Donnelly, Justin; Repp, Allen B (1 February 2020). "Promoting appropriate utilisation of laboratory tests for inflammation at an academic medical centre" (in en). BMJ Open Quality 9 (1): e000788. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000788. ISSN 2399-6641. PMC PMC7047503. PMID 32098777. https://qir.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000788.

- ↑ Morgan, Simon; Morgan, Andy; Kerr, Rohan; Tapley, Amanda; Magin, Parker (1 September 2016). "Test ordering by GP trainees: Effects of an educational intervention on attitudes and intended practice". Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien 62 (9): 733–741. ISSN 1715-5258. PMC 5023346. PMID 27629671. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27629671.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Juskewitch, Justin E.; Norgan, Andrew P.; Johnson, Ryan D.; Trivedi, Vipul A.; Hanson, Curtis A.; Block, Darci R. (1 April 2019). "Impact of an electronic decision support rule on ESR/CRP co-ordering rates in a community health system and projected impact in the tertiary care setting and a commercially insured population" (in en). Clinical Biochemistry 66: 13–20. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.01.009. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0009912018311652.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Larochelle, Marc R.; Knight, Amy M.; Pantle, Hardin; Riedel, Stefan; Trost, Jeffrey C. (1 November 2014). "Reducing Excess Cardiac Biomarker Testing at an Academic Medical Center" (in en). Journal of General Internal Medicine 29 (11): 1468–1474. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2919-5. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC PMC4238205. PMID 24973056. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11606-014-2919-5.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Taher, Jennifer; Beriault, Daniel R.; Yip, Drake; Tahir, Shafqat; Hicks, Lisa K.; Gilmour, Julie A. (1 July 2020). "Reducing free thyroid hormone testing through multiple Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles" (in en). Clinical Biochemistry 81: 41–46. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.05.004. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0009912020303106.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gilmour, Julie A.; Weisman, Alanna; Orlov, Steven; Goldberg, Robert J.; Goldberg, Alyse; Baranek, Hayley; Mukerji, Geetha (1 June 2017). "Promoting resource stewardship: Reducing inappropriate free thyroid hormone testing" (in en). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 23 (3): 670–675. doi:10.1111/jep.12698. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jep.12698.

- ↑ Mostofian, Fargoi; Ruban, Cynthiya; Simunovic, Nicole; Bhandari, Mohit (1 January 2015). "Changing physician behavior: what works?". The American Journal of Managed Care 21 (1): 75–84. ISSN 1936-2692. PMID 25880152. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25880152.

- ↑ Lippi, Giuseppe; Brambilla, Marco; Bonelli, Patrizia; Aloe, Rosalia; Balestrino, Antonio; Nardelli, Anna; Ceda, Gian Paolo; Fabi, Massimo (1 November 2015). "Effectiveness of a computerized alert system based on re-testing intervals for limiting the inappropriateness of laboratory test requests". Clinical Biochemistry 48 (16-17): 1174–1176. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.06.006. ISSN 1873-2933. PMID 26074445. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26074445.

- ↑ Parkhurst, Emily; Calonico, Elise; Noh, Grace (31 July 2020). "Medical Decision Support to Reduce Unwarranted Methylene Tetrahydrofolate Reductase (MTHFR) Genetic Testing". Journal of Medical Systems 44 (9): 152. doi:10.1007/s10916-020-01615-5. ISSN 1573-689X. PMID 32737598. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32737598.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation, spelling, and grammar. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.