Journal:Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry for multi-residue analysis of mycotoxins and pesticides in botanical nutraceuticals

| Full article title |

Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry for multi-residue analysis of mycotoxins and pesticides in botanical nutraceuticals |

|---|---|

| Journal | Toxins |

| Author(s) | Narváez, Alfonso; Rodríguez-Carrasco, Yelko; Castaldo, Luigi; Izzo, Luana; Ritieni, Alberto |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Naples “Federico II”, University of Valencia |

| Primary contact | Email: yelko dot rodriguez at uv dot es |

| Year published | 2020 |

| Volume and issue | 12(2) |

| Page(s) | 114 |

| DOI | 10.3390/toxins12020114 |

| ISSN | 2072-6651 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/12/2/114/htm |

| Download | https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/12/2/114/pdf (PDF) |

|

|

This article should be considered a work in progress and incomplete. Consider this article incomplete until this notice is removed. |

Abstract

Cannabidiol (CBD) food supplements made of Cannabis sativa L. extracts have quickly become popular products due to their health-promoting effects. However, potential contaminants, such as mycotoxins and pesticides, can be coextracted during the manufacturing process and placed into the final product. Accordingly, a novel methodology using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS) was developed to quantify 16 mycotoxins produced by major C. sativa fungi, followed by a post-target screening of 283 pesticides based on a comprehensive spectral library. The validated procedure was applied to 10 CBD-based products. Up to six different Fusarium mycotoxins were found in seven samples, the most prevalent being zearalenone (60%) and enniatin B1 (30%), both found at a maximum level of 11.6 ng/g. Co-occurrence was observed in four samples, including one with enniatin B1, enniatin A, and enniatin A1. On the other hand, 46 different pesticides were detected after retrospective analysis. Ethoxyquin (50%), piperonyl butoxide (40%), simazine (30%), and cyanazine (30%) were the major residues found. These results highlight the necessity of monitoring contaminants in food supplements in order to ensure safe consumption, even more considering the increasing trend in their use. Furthermore, the developed procedure is proposed as a powerful analytical tool to evaluate the potential mycotoxin profile of these particular products. To our knowledge, this represents the first multi-class analysis of CBD-based supplements regarding mycotoxins and pesticide residues using high-resolution mass spectrometry techniques.

Keywords: mycotoxins, pesticides, Q-Exactive Orbitrap, CBD capsule, nutraceutical

Introduction

Nutrition is known to be an essential component of quality state of health, and having an unbalanced diet can lead to several disorders and diseases.[1] Due to current lifestyles, new, convenient ways to maintain proper dietary habits are required. Nutraceuticals have emerged as an alternative to increase the input of nutrients, contributing to an improvement in health. These products are bioactive compounds naturally occurring in food or produced de novo in human metabolism, biologicals, or botanicals, each intended to impart a physiological or medicinal effect after ingestion.[2] They can be delivered either in foods and beverages or in other non-conventional forms, such as capsules, tablets, powders, or liquid extracts. In terms of marketing, nutraceuticals include a large number of different products packaged for specific groups by age, gender, physical condition, and activity level. The global market was valued at U.S. $109 billion in 2015 and was projected to reach U.S. $180 billion by 2020.[3]

Inside the variety of products classified as nutraceuticals, food supplements based on botanical ingredients represent the second largest segment, behind vitamins and minerals. Most recently, cannabidiol (CBD) dietary supplements made of Cannabis sativa L. extracts have quickly become popular products. CBD is a phytocannabinoid present in the resin secreted from trichomes in female C. sativa plants and is mainly found in inflorescences. The bioactivity of this compound has been related to an enhancement of its antioxidant and neurological activity, among others, by the promotion of several metabolic pathways.[4][5][6] However, the European Union (E.U.) does not consider CBD supplements as a novel food[7] and lets member states set their own rules over its marketing, leading to a convoluted situation in terms of regulation. Despite several ambiguities in its legislation, the European market for CBD-based supplements was valued at U.S. $318 million in 2018, with a strong growth projection.[8]

Due to the complex nature of C. sativa and other botanicals, potential contaminants can be coextracted during the different stages of the manufacturing process and placed into the final product. Among all the potential non-desirable compounds in herbal-based supplements, mycotoxins and pesticides are the most commonly reported.[9][10] Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites mainly produced by the fungi genera Fusarium, Aspergillus, Penicillium, Claviceps, and Alternaria. These compounds can be present in food and feed commodities and display immunosuppressive, nephrotoxic, or carcinogenic effects, among others.[11] According to their carcinogenic potential, some mycotoxins, like aflatoxins, have been included in the classification list of human carcinogens provided by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).[12] These mycotoxins are produced by the genera Aspergillus, which has been categorized as a major fungus occurring in C. sativa inflorescences alongside other mycotoxin producing fungi, like Fusarium spp., so different mycotoxins could be also expected.[13][14] On the other hand, pesticides include a broad range of compounds routinely applied to protect crops from different pests. However, residues coming from these products can accumulate in plants intended for human consumption, leading to several health issues related to neurotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and pulmonotoxicity, as well as developmental and reproductive disorders.[15][16][17][18]

In terms of regulation, maximum residue limits (MRL) for different types of contaminants have been set by the E.U. Regulation (EC) No. 396/2005[19] establishes limits for pesticides, whereas Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006[20] covers mycotoxins, attaching maximum limits in food and feeds. Nevertheless, nutraceutical products are not considered by the legislation yet; however, due to a potential carryover during the manufacturing process, contamination could be expected not only in raw material, but also in other by-products. Moreover, several studies have reported the sole presence of pesticides[21][22], mycotoxins[23][24], and both types of contaminants[25][26][27] in diverse food supplements, emphasizing the necessity to evaluate the contamination profile of these products considering their rising consumption and popularity.

To overcome this point, the development of analytical procedures is needed. Concerning the extraction of contaminants, QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged and safe)[21][23][24] and “dilute and shoot” procedures have been recently applied to food supplements delivered as gelatin capsules, traditional capsules, tablets, powder extracts or liquid presentations.[25][26][27] Analytical methods used in the detection and quantification of contamination include ELISA detection[28], gas chromatography (GC) coupled with mass spectrometry (MS)[22] and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS)[23][24], and high-resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Q-Orbitrap HRMS).[25][26][27] Due to its high resolving power, sensitivity and accurate mass measurement, high-resolution mass spectrometry stands as a suitable alternative for evaluating a large number of contaminants present in complex matrices at low concentrations. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to provide an analysis of pesticide residues and mycotoxins produced by major C. sativa fungi occurring in CBD-based food supplements using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometry. To achieve this, a novel methodology was developed in order to identify and quantify 16 mycotoxins after evaluating different extraction procedures, followed by a post-target screening of 283 pesticides based on a comprehensive spectral library. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first multi-class analysis of CBD-based supplements through the use of high-resolution mass spectrometry techniques.

Results

Optimization of extraction procedure

The molecular complexity of this matrix demands an effective extraction in order to detect and quantify several mycotoxins in a reliable way. A QuEChERS methodology previously developed on this typology of sample[24] was selected as the starting point, whereas different volumes of extraction solvent and the type of sorbent for clean-up was tested.

Evaluation of the volume of extraction solvent

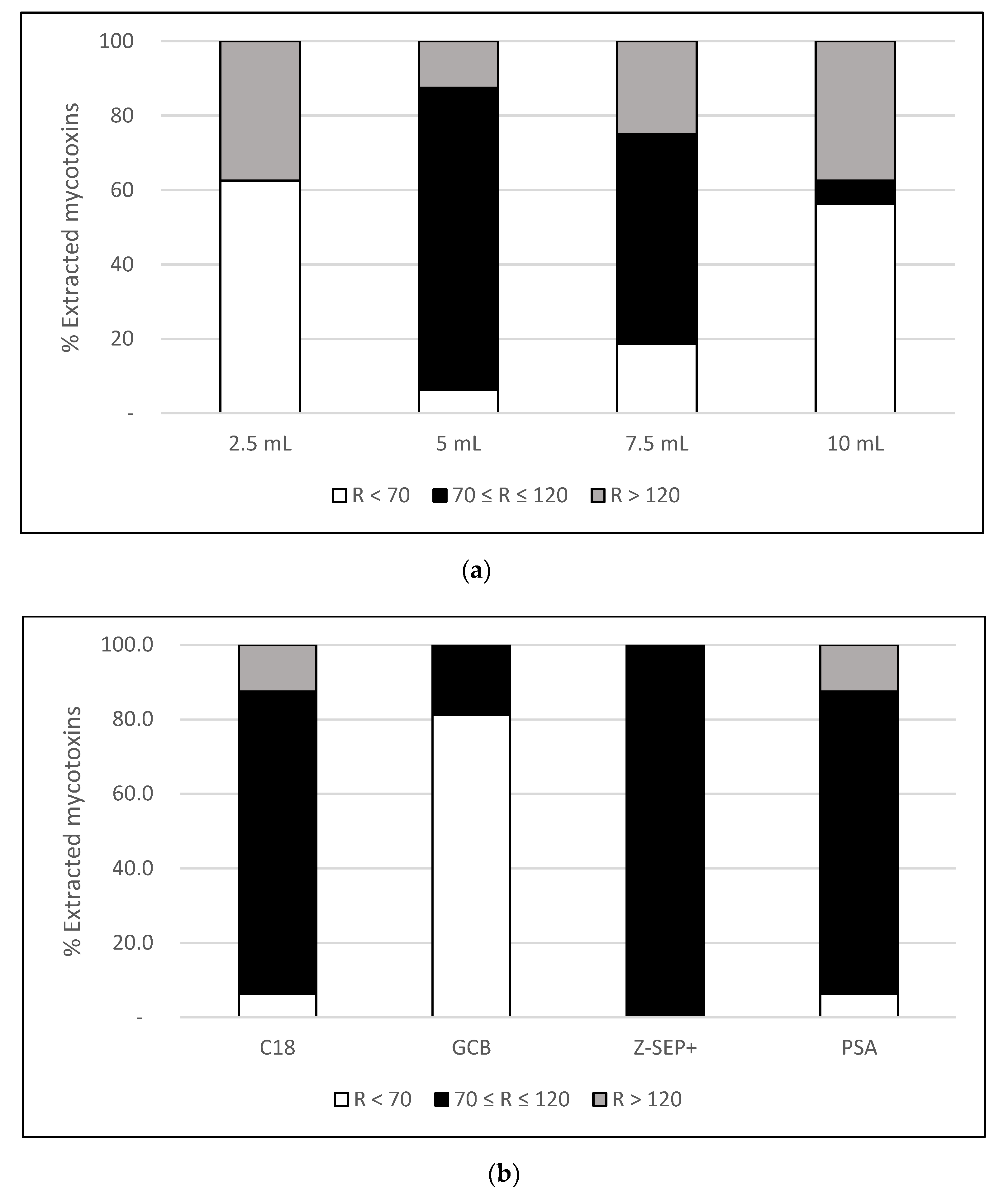

The extraction procedure was first evaluated in triplicate by spiking the sample at 10 ng/g using the following volumes of extraction solvent per gram of sample: 2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10 mL.

The extraction performed with 2.5 mL showed recovery values below the minimum limit (70%) for the vast majority of the studied analytes as a consequence of solvent saturation (Figure 1a). Satisfactory recoveries (70–120%) were obtained after performing the extraction with 5 mL of solvent for the majority of compounds, with the exception of β-ZEL (155%) and ZAN (150%), which were significantly more efficient than the other volumes tested (p < 0.05). On the other hand, the extractions performed with 7.5 and 10 mL showed a gradual decrease in recoveries due to the larger dilution of the analytes. Therefore, 5 mL of AcN was selected as the optimal volume of extraction solvent for this type of CBD capsule.

|

Evaluation of the type of sorbent for clean-up

The molecular composition of the soft gel capsules mainly consists on fatty acids and proteins. Because of the complex nature of this matrix, an efficient clean-up is required in order to avoid interference with the analytes. To achieve this, clean-up with different sorbents (100 mg) was performed, including C18 (as previously suggested[24]), GCB, Z-Sep+, and PSA.

PSA exhibited a good performance for the vast majority of analytes (Figure 1b, above) but was unable to recover other important mycotoxins, such as AFB1 and AFG1. The moderate affinity of PSA with polar compounds may explain low recoveries for aflatoxins, being consistent with other works based on oily matrices.[29][30] Similarly, extraction with C18 was efficient for most compounds, and only some low-polarity mycotoxins showed recoveries out of the range set, like ZAN (150%) and β-ZEL (155%). Clean-up using GCB showed poor results, allowing us to detect only NEO (85%), HT-2 (89%), and T-2 (89%). This sorbent is able to retain planar molecules; additionally, mycotoxin adsorption has been previously reported[31], which might be the reason for the low recoveries obtained here. Finally, extraction performed with Z-Sep+ showed satisfactory recoveries (70–120%) for all the mycotoxins studied.

On the other hand, the influence of the matrix was minimal (80% ≤ signal suppression/enhancement (SSE) ≤ 120%) for all targeted analytes when using Z-Sep+ and PSA. Clean-up based on Z-Sep+ has been successfully applied to the extraction of analytes from lipid matrices.[32][33] Furthermore, Z-Sep+ is also able to form irreversible links with carboxylic groups present in proteins[34], standing as the most suitable sorbent for the here-analyzed matrix. Similarly, the use of PSA has been suggested to remove coextracted fatty acids and other ionic lipids.[35]

On the contrary, a strong matrix effect was evidenced for half the analytes when using C18 and GCB. Signal suppression was detected after using C18, obtaining SSE ranging from 40% to 69%, whereas signal enhancement occurred after GCB clean-up, with SSE increasing from 128% to 167%. Since both sorbents have a preferential affinity for non-polar compounds, matrix interferents were not fully removed but coextracted. The presence of these coextracted species can change the ionization efficiency, leading to improper SSE and an unreliable quantification. Although no significant differences were observed between the use of Z-Sep+ and PSA (p > 0.05), Z-Sep+ was chosen because of its better performance minimizing matrix interference.

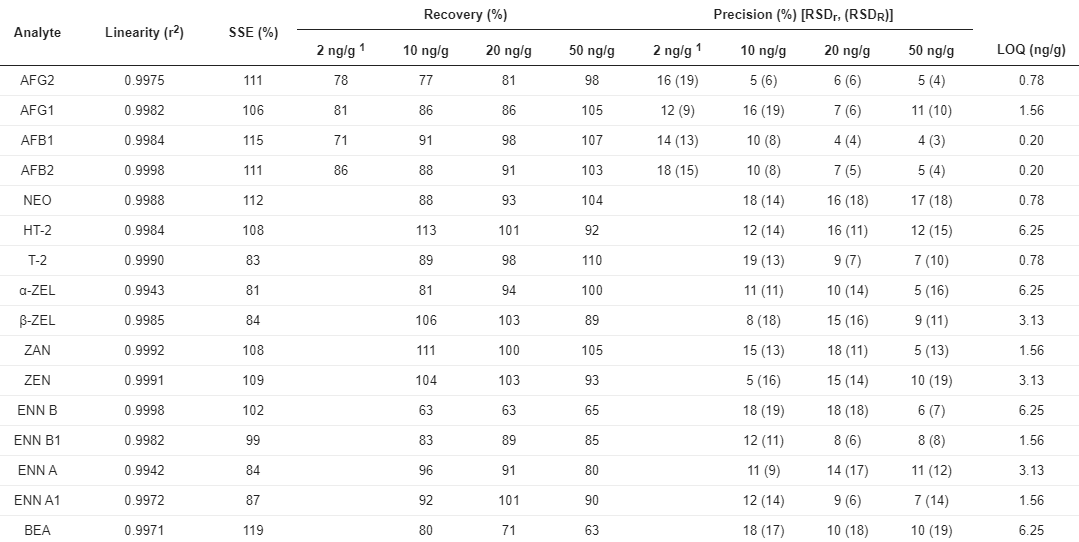

Analytical method validation

The optimized method was validated for the simultaneous extraction of 16 mycotoxins in CBD-based products. Results are shown in Table 1. Good linearity was observed for all analytes in the range assessed (0.20–100 ng/g), with regression coefficients (r2) above 0.990 and a deviation ≤20% for each level of the calibration curve. Comparison between calibration curves built in a blank matrix and in neat solvent showed a minimal interference in the matrix (±20%) for the studied analytes. Hence, external calibration curves were used for quantification purposes. Limits of quality (LOQs) obtained for all studied analytes were between 0.20 and 6.25 ng/g. Regarding trueness, recovery values corresponding to a fortification level of 20 ng/g ranged between 63 and 103% and between 63 and 113% for the lowest fortification level (10 ng/g). Referring to the additional spiking level (2 ng/g) for aflatoxins, recoveries ranged between 63% and 86%. Precision study revealed both RSDr and RSDR values below 20% for all the mycotoxins analyzed. These results confirmed that the optimized procedure is suitable for a reliable quantification of the mycotoxins analyzed, fulfilling the criteria set by Commission Decision 2002/657/EC.[36]

|

Table 2 reviews the available literature regarding mycotoxins in herbal-based supplements. As shown, the here-obtained LOQs were lower than the ones reported in previous studies using UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS. As established by Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006[20], maximum limits for aflatoxins in many food matrices must not reach levels which are below those LOQs (5 ng/g), whereas LOQs obtained in this study were between 5 and 25 times lower. Other analytical methods based on low resolution mass spectrometry[37] required longer and more complicated extraction procedures than the QuEChERS developed here. Even ELISA detection has been used for quantification of mycotoxins in medicinal herbs[28], but a very specific extraction had to be performed for different groups of analytes using several multi-functional columns. The QuEChERS procedure developed in this study, in combination with UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap mass spectrometry, was extremely simple and reliable, allowing for the quantification of all mycotoxins with high sensitivity.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

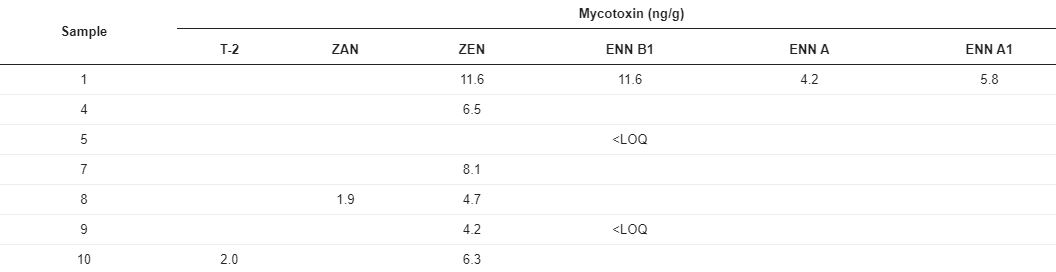

Application to commercial CBD-based products

The validated UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap HRMS procedure was applied to 10 commercially available samples in order to evaluate the occurrence of mycotoxins. Results are shown in Table 3. A considerable occurrence of mycotoxins was observed, since contamination with at least one analyte was found in 70% of the samples. Up to six different mycotoxins (T-2, ZAN, ZEN, ENNB1, ENNA, ENNA1) were quantified at a range from below LOQ to 11.6 ng/g, all produced by Fusarium genera, reported as a major C. sativa pathogen fungus.[14] Previous studies regarding mycotoxins in different herbal-based extracts have revealed the occurrence of similar mycotoxins independently of the matrix and the dosage form (Table 2, above). Despite the fact that the percentage of positive samples varied among the different studies (19–99%), when the sensitivity of the analytical method increased, reaching lower LOQs, the number of positive samples dramatically increased. This indicated that mycotoxin contamination in herbal-based products at low levels is frequent.

|

In the here-analyzed samples, ZEN appeared to be the most common mycotoxin, with an incidence of 60% and concentration levels ranging from 4.2 to 11.6 ng/g (mean level = 6.9 ng/g). A high incidence of ZEN has also been previously reported in supplements made of different herbals from Czech and U.S. retail markets (84%, n = 69) at a wide range of concentrations (5–824 ng/g, mean value = 75.7 ng/g).[24] Moreover, ZEN was previously found in 96% of medicinal herbals from Spain (n = 84) as well, but in a tighter range (1–44.1 ng/g, mean value = 8.9 ng/g).[28]

Referring to T-2, results reported contamination in one sample at 2.0 ng/g, in contrast with the prevalent presence of T-2 in 78% (n = 69) of the same Czech and U.S. samples, at concentrations rising from 69 to 1,870 ng/g (mean value = 162 ng/g).[24] High levels of T-2 were also observed in milk thistle samples from Spain (363–453.9, mean value = 408.9 ng/g) in only two out of seven samples.[39] In the other hand, T-2 was quantified in 98% (n = 84) of the Spanish medicinal herbals, but in much lower concentrations (0.6–256 ng/g, mean value = 22.645 ng/g).[28]

Similarly, ZAN was quantified in one sample at 1.9 ng/g. This mycotoxin has been scarcely targeted in dietary supplement studies, but it has been previously quantified at similar concentrations as those here-reported in two samples of Chinese medicinal herbals (n = 33).[40]

Results also showed ENN contamination. ENNB1, ENNA, and ENNA1 were found in the same sample at 11.6, 4.2 and 5.8 ng/g, respectively, whereas ENNB1 was detected in two other samples below the LOQ (1.56 ng/g). These emerging Fusarium mycotoxins have been previously found in herbal products (84–91%, n = 69) widely ranging from 5 ng/g up to 10,900 ng/g (mean value = 354 ng/g).[24] Similarly, ENNB1 was the most common toxin out of these emerging Fusarium mycotoxins, being consistent with the results here obtained.

All the mycotoxins found in the present study correspond to low- to non-polar compounds, which should be prevalently expected due to the nature of the matrix.

Co-occurrence of at least two mycotoxins was also observed in four out of 10 samples. Results showed the presence of ZEN in combination with ENNs B1, A and A1, ZAN, or T-2, which are common associations found by previous studies in herbal-based supplements.[24][28] It must be noted that synergic or additive effects have been observed as a consequence of these combinations in in vitro assays.[41] Based on what has been discussed and considering the uprising trend of C. sativa-based products, alongside the use of environment-friendly raw materials cultivated without pesticides, quality controls regarding mycotoxins should be set for these products in order to ensure safe consumption.

References

- ↑ Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A. et al. (2019). "Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". Lancet 393 (10184): 1958–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8. PMC PMC6899507. PMID 30954305. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6899507.

- ↑ Almada, A.L. (2019). "Chapter 1: Nutraceuticals and functional foods: Innovation, insulation, evangelism, and evidence". In Bagchi, D.. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the United States and around the World (3rd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 9780128164679.

- ↑ Binns, C.W.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, A.H. (2018). "Problems and Prospects: Public Health Regulation of Dietary Supplements". Annual Review of Public Health 39: 403–20. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013638. PMID 29272167.

- ↑ Zuardi, A.W. (2008). "Cannabidiol: From an inactive cannabinoid to a drug with wide spectrum of action". Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 30 (3): 271–80. doi:10.1590/s1516-44462008000300015. PMID 18833429.

- ↑ Casares, L.; García, V.; Garrido-Rodríguez, M. et al. (2020). "Cannabidiol induces antioxidant pathways in keratinocytes by targeting BACH1". Redox Biology 28: 101321. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2019.101321. PMC PMC6742916. PMID 31518892. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6742916.

- ↑ Maroon, J.; Bost, J. (2018). "Review of the neurological benefits of phytocannabinoids". Surgical Neurology International 9: 91. doi:10.4103/sni.sni_45_18. PMC PMC5938896. PMID 29770251. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5938896.

- ↑ "Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on novel foods, amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1852/2001". EUR-Lex. European Union. 11 December 2015. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015R2283.

- ↑ "Iternational CBD and Cannabis Market Landscape". Brightfield Group Data Portals. Brightfield Group. https://www.brightfieldgroup.com/international-cbd-cannabis-market-landscape.

- ↑ Santini, A.; Cammarata, S.M.; Capone, G. et al. (2018). "Nutraceuticals: Opening the debate for a regulatory framework". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 84 (4): 659–672. doi:10.1111/bcp.13496. PMC PMC5867125. PMID 29433155. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5867125.

- ↑ Gulati, O.P.; Ottaway, P.B.; Jenning, S. et al. (2019). "Chapter 20: Botanical nutraceuticals (food supplements and fortified and functional foods) and novel foods in the EU, with a main focus on legislative controls on safety aspects". In Bagchi, D.. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the United States and around the World (3rd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 277–321. ISBN 9780128164679.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y.; Fattore, M.; Albrizio, S. et al. (2015). "Occurrence of Fusarium mycotoxins and their dietary intake through beer consumption by the European population". Food Chemistry 178: 149–55. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.092. PMID 25704695.

- ↑ Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Toman, J. et al. (2017). "Mycotoxins as human carcinogens-the IARC Monographs classification". Mycotoxin Research 33 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1007/s12550-016-0265-7. PMID 27888487.

- ↑ McKernan, K.; Spangler, J.; Zhang, L. et al. (2015). "Cannabis microbiome sequencing reveals several mycotoxic fungi native to dispensary grade Cannabis flowers". F1000Research 4: 1422. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7507.2. PMC PMC4897766. PMID 27303623. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4897766.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 McHardy, I.; Romanelli, A.; Harris, L.J. et al. (2018). "Infectious risks associated with medicinal Cannabis: Potential implications for immunocompromised patients?". Journal of Infection 76 (5): 500–1. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2018.01.010. PMID 29408325.

- ↑ Atapattu, S.N.; Johnson, K.R.D. (2020). "Pesticide analysis in cannabis products". Journal of Chromatography A. 1612: 460656. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2019.460656. PMID 31679712.

- ↑ Choudri, B.S.; Charabi, Y. (2019). "Pesticides and herbicides". Water Environment Research 91 (10): 1342-1349. doi:10.1002/wer.1227. PMID 31523896.

- ↑ Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. (2017). "Pesticides: An update of human exposure and toxicity". Archives of Toxicology 91 (2): 549-599. doi:10.1007/s00204-016-1849-x. PMID 27722929.

- ↑ Ye, M.; Beach, J.; Martin, J.W. et al. (2017). "Pesticide exposures and respiratory health in general populations". Journal of Environmental Sciences 51: 361–70. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2016.11.012. PMID 28115149.

- ↑ "Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on maximum residue levels of pesticides in or on food and feed of plant and animal origin and amending Council Directive 91/414/EECText with EEA relevance". EUR-Lex. European Union. 16 March 2005. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32005R0396.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs". EUR-Lex. European Union. 20 December 2006. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32006R1881.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Jeong, M.L.; Zahn, M.; Trinh, T. et al. (2008). "Pesticide residue analysis of a dietary ingredient by gas chromatography/selected-ion monitoring mass spectrometry using neutral alumina solid-phase extraction cleanup". Journal of AOAC International 91 (3): 630-6. PMID 18567310.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 González-Martín, M.I.; Revilla, I.; Betances-Salcedo, E.V. et al. (2018). "Pesticide residues and heavy metals in commercially processed propolis". Microchemical Journal 143: 423–29. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2018.08.040.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Vaclavik, L.; Vaclavikova, M.; Begley, T.H. et al. (2013). "Determination of multiple mycotoxins in dietary supplements containing green coffee bean extracts using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 61 (20): 4822-30. doi:10.1021/jf401139u. PMID 23631685.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 24.9 Veprikova, Z.; Zachariasova, M;. Dzuman, Z. et al. (2015). "Mycotoxins in Plant-Based Dietary Supplements: Hidden Health Risk for Consumers". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 63 (29): 6633-43. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02105. PMID 26168136.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Martínez-Domínguez, G.; Romero-González, R.; Garrido Frenich, A. (2015). "Determination of toxic substances, pesticides and mycotoxins, in ginkgo biloba nutraceutical products by liquid chromatography Orbitrap-mass spectrometry". Microchemical Journal 118: 124–30. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2014.09.002.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Martínez-Domínguez, G.; Romero-González, R.; Garrido Frenich, A. (2016). "Multi-class methodology to determine pesticides and mycotoxins in green tea and royal jelly supplements by liquid chromatography coupled to Orbitrap high resolution mass spectrometry". Food Chemistry 197 (Pt. A): 907-15. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.070. PMID 26617033.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Martínez-Domínguez, G.; Romero-González, R.; Arrebola, F.J. et al. (2016). "Multi-class determination of pesticides and mycotoxins in isoflavones supplements obtained from soy by liquid chromatography coupled to Orbitrap high resolution mass spectrometry". Food Control 59: 218–24. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.05.033.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 Santos, L.; Marín, S.; Sanchis, V. et al. (2009). "Screening of mycotoxin multicontamination in medicinal and aromatic herbs sampled in Spain". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 89 (10): 1802–7. doi:10.1002/jsfa.3647.

- ↑ Zhao, H.; Chen, X.; Shen, C. et al. (2017). "Determination of 16 mycotoxins in vegetable oils using a QuEChERS method combined with high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Food Additives and Contaminates Part A 34 (2): 255–64. doi:10.1080/19440049.2016.1266096. PMID 27892850.

- ↑ Hidalgo-Ruiz, J.L;. Romero-González, R.; Martínez Vidal, J.L. et al. (2019). "A rapid method for the determination of mycotoxins in edible vegetable oils by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Food Chemistry 288: 22–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.003. PMID 30902285.

- ↑ Myresiotis, C.K.; Testempasis, S;. Vryzas, Z. et al. (2015). "Determination of mycotoxins in pomegranate fruits and juices using a QuEChERS-based method". Food Chemistry 182: 81–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.141. PMID 25842312.

- ↑ Han, L;. Matarrita, J.; Sapozhnikova, Y. et al. (2015). "Evaluation of a recent product to remove lipids and other matrix co-extractives in the analysis of pesticide residues and environmental contaminants in foods". Journal of Chromatography A 182: 81–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.141. PMID 25842312.

- ↑ Rajski, Ł.; Lozano, A;. Uclés, A. et al. (2013). "Determination of pesticide residues in high oil vegetal commodities by using various multi-residue methods and clean-ups followed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A 1304: 109–20. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2013.06.070. PMID 23871559.

- ↑ Lozano, A.; Rajski, Ł.; Uclés, S. et al. (2014). "Evaluation of zirconium dioxide-based sorbents to decrease the matrix effect in avocado and almond multiresidue pesticide analysis followed by gas chromatography tandem mass spectrometry". Talanta 118: 68–83. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.09.053. PMID 24274272.

- ↑ Tuzimski, T.; Szubartowski, S. (2019). "Method Development for Selected Bisphenols Analysis in Sweetened Condensed Milk from a Can and Breast Milk Samples by HPLC-DAD and HPLC-QqQ-MS: Comparison of Sorbents (Z-SEP, Z-SEP Plus, PSA, C18, Chitin and EMR-Lipid) for Clean-Up of QuEChERS Extract". Molecules 24 (11): E2093. doi:10.3390/molecules24112093. PMC PMC6600471. PMID 31159388. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6600471.

- ↑ "2002/657/EC: Commission Decision of 12 August 2002 implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC concerning the performance of analytical methods and the interpretation of results". EUR-Lex. European Union. 17 August 2002. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32002D0657.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Han, Z.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, J. et al. (2012). "Multianalysis of 35 mycotoxins in traditional Chinese medicines by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry coupled with accelerated solvent extraction". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 60 (33): 8233-47. doi:10.1021/jf301928r. PMID 22823451.

- ↑ Tournas, V.H.; Sapp, C.; Trucksess, M.W. (2012). "Occurrence of aflatoxins in milk thistle herbal supplements". Food Additives and Contaminated Part A. 29 (6): 994–9. doi:10.1080/19440049.2012.664788. PMID 22439650.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Arroyo-Manzanares, N.; García-Campaña, A.M.; Gámiz-Gracia, L. (2013). "Multiclass mycotoxin analysis in Silybum marianum by ultra high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using a procedure based on QuEChERS and dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction". Journal of Chromatography A. 1282: 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2013.01.072. PMID 23415469.

- ↑ Han, Z.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, H. et al. (2011). "A rapid method for simultaneous determination of zearalenone, α-zearalenol, β-zearalenol, zearalanone, α-zearalanol and β-zearalanol in traditional Chinese medicines by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography B. 879 (5–6): 411–20. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.12.028. PMID 21242113.

- ↑ Smith, M.C.; Madec, S.; Coton, E. et al. (2016). "Natural Co-Occurrence of Mycotoxins in Foods and Feeds and Their in vitro Combined Toxicological Effects". Toxins 8 (4): 94. doi:10.3390/toxins8040094. PMC PMC4848621. PMID 27023609. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4848621.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The references are slightly out of order compared to the original, starting at reference 38, due to non-sequential ordering in the original Table 2.