Journal:Big data as a driver for clinical decision support systems: A learning health systems perspective

| Full article title | Big data as a driver for clinical decision support systems: A learning health systems perspective |

|---|---|

| Journal | Frontiers in Digital Humanities |

| Author(s) |

Dagliati, Arianna; Tibolloa, Valentina; Sacchi, Lucia; Malovini, Alberto; Limongelli, Ivan; Gabetta, Matteo; Napolitano, Carlo; Mazzanti, Andrea; De Cata, Pasquale; Chovato, Luca; Priori, Sylvia; Bellazzi, Riccardo |

| Author affiliation(s) | Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, University of Manchester, Università degli Studi di Pavia, Engenome s.r.l., Biomeris s.r.l. |

| Primary contact | Email: riccardo dot bellazzi at unipv dot it |

| Editors | Cavallo, Pierpaolo |

| Year published | 2018 |

| Volume and issue | 5 |

| Page(s) | 8 |

| DOI | 10.3389/fdigh.2018.00008 |

| ISSN | 2297-2668 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdigh.2018.00008/full |

| Download | https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fdigh.2018.00008/pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Big data technologies are nowadays providing health care with powerful instruments to gather and analyze large volumes of heterogeneous data collected for different purposes, including clinical care, administration, and research. This makes possible to design IT infrastructures that favor the implementation of the so-called “Learning Healthcare System Cycle,” where healthcare practice and research are part of a unique and synergistic process. In this paper we highlight how "big-data-enabled” integrated data collections may support clinical decision-making together with biomedical research. Two effective implementations are reported, concerning decision support in diabetes and in inherited arrhythmogenic diseases.

Keywords: big data, learning health care cycle, data warehouses, data integration, data analytics

Introduction

Following a broadly recognized definition, big data is data “whose scale, diversity, and complexity require new architecture, techniques, algorithms, and analytics to manage it and extract value and hidden knowledge from it.”[1] This definition embraces the multifactorial nature of this kind of data and the technological challenges implied. The integration of different sources of information, from primary and secondary care to administrative data, seems a substantial opportunity that big data provides to healthcare.[2][3][4][5][6] Such integration may allow depicting a novel view of patients' care processes and of single patient's behaviors while taking into account the multifaceted aspects of clinical and chronic care.

The interest in the collection of large and heterogeneous healthcare data sources finds a distinctive application in the definition of novel data-driven decision support systems.[7][8][9] Several authors[8][9][10] define two main fields where researchers should address their efforts to produce valuable results in this area: (i) the secondary use of data to create new evidence and glean important insights to make better clinical decision or to reshape health care organizational components; and (ii) the detection of novel correlations from asynchronous events to allow clinicians to promptly identify potential complications, timely adjust treatments, or help analyze similar manifestations in clinical diagnoses. To pledge better renewed decision making, and consequent successful clinical outcomes, big-data-enabled health care systems should effectively integrate advanced computational tools, including novel similarity measures for patients' stratification, and predictive analytics for risk assessment and selection of therapeutic interventions.[11][12][13][14]

The availability of new data sources is thus leading to the development of a novel model of healthcare, able to fully exploit the potentials of data-driven decision making. The main consequence is that big data will not only be an important enabler for research, but also for the clinical and organizational decision making. We will discuss this perspective within the context of the so-called “Learning Healthcare System Cycle” (LHSC).[15][16][17][18][19][20] We demonstrate the importance of leveraging on LHSC solutions in developing next-generation clinical and organizational decision systems, as follows: (i) we describe a possible formalization for the use of the learning healthcare aystem, proposing a conceptual solution based on state-of-the-art technologies for data production; and (ii) we present two systems implanted upon the LHSC as proof of concept of the validity of the formalized concepts in different clinical scenarios.

Big data and the learning healthcare system cycle

Novel and essential directions in the use of big data for healthcare have been recently redefined within the medical informatics community.[21] Specifically, the well-known conceptual approach of the “data, information, and knowledge” continuum has been reconsidered as the LHSC, where healthcare practice and research should be part of a unique and synergic process. The first main novelty of this approach is to emphasize that clinical practice and research are complementary agents in the generation of data and knowledge.

The role of informatics is to provide the right tools to turn data into information, and information into knowledge, helping to understand deep data relations by retrieving and extracting underlying patterns. Moreover, informatics is crucial for the deployment of the acquired knowledge to support patient care and, ultimately, to guide individual behavior.

Our prospective is that the use of big data in medical informatics will be equally important in the different phases of the LHSC: from research to data driven decision-making. LSHC is indeed based on these two complementary actions, the first one focused on the exploitation of medical generated data for research purposes (care informs research), and the second one focused on the development of novel systems leveraging big data to guide clinical decision making (research informs care).

Care informs research: Research

In clinical practice, data is mostly collected from electronic health records (EHR), through which recent widespread adoption has made available a unique source of clinical information for research. The EHR can be used to extract and interpret clinical data, to automatically support clinical research, and improve quality of care. Specifically, EHR-based phenotyping uses data captured in the delivery of care to identify individuals or cohorts with conditions or events relevant to clinical studies[22][23][24] Some distinguishing aspects of the current literature include: (i) considering the temporal nature of the data—and explicitly including not only clinical information from EHR but also process information from administrative databases—recent methods allow, for example, the extraction of care-flows that highlight frequent patients' trajectories in terms of disease evolution as well as in terms of patterns of care; (ii) allow for computing patients' similarity by resorting to advanced “multimodal” data fusion strategies, including deep learning and tensor factorization; and (iii) fully apply natural language processing pipelines as enablers to integrate in the analytical process data and knowledge hidden in textual reports.

Research informs care: Data-driven decision making

Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) have been traditionally defined as software designed to aid clinical decision making by adapting computerized clinical guidelines and protocols to individual patient characteristics.[25] While it is recognized that developing and deploying CDSSs can be very beneficial in contexts that require complex decision-making, such as chronic disease management, their use in routine clinical practice is currently still limited.[26] Possible causes are related to poor user interfaces, lacking integration with EHRs, and limited analytics capabilities that do not allow data-driven reasoning.

We believe that, in order to provide successful decision support, CDSSs should comply with basic requirements, including: (i) rich contents in terms of knowledge, references, and data evidences; (ii) the capability of processing huge amounts of data with fast response times; and (iii) implementations that are intuitive, appealing, and able to catch users' attention while not delaying clinical actions. These features translate into the fundamental CDSS components: data and knowledge repositories, inference engines, and user interfaces. It is worth noticing that IT infrastructures designed to support research can also be used to assist clinical decision-making. An interesting paradigm is represented by the so-called “sidecar” approach, where the same data warehouse is used to analyze patients' cohorts at a population level and as an instrument to enable “case-based” reasoning in front of a complex clinical case by extracting similar patients and potential treatments.

Use of big data for clinical decision support: Available solutions and systems

Several conceptual design elements and software components are nowadays available to support the construction of systems for implementing LHSC.

Some well-known current initiatives and networks to support big data research include the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) projects[27], eMERGE[28], and PCORNet.[29] BD2K is an extensive funding initiative that encompasses several aspects of the enhancement of big data in biomedical research: from accessibility and reusability of data, to the development of novel methodologies and tools for analyzing big data. The eMERGE network serves to develop and share high-throughput clinical phenotyping algorithms in support of precision medicine. It includes several tools, like PheKB, a collaborative knowledge base for phenotype discovery and validation. In light of clinical decision support, the eMERGE network proposed the use of infobuttons[30][31] as a decision support tool to provide context-specific links within electronic health records to relevant genomic medicine content. PCORNet is aimed at improving the capacity to conduct comparative clinical effectiveness research thanks to patient-centered common data models. These data models leverage standard terminologies and coding systems for healthcare (including ICD, SNOMED, CPT, HCPSC, and LOINC) to enable interoperability with and responsiveness to evolving data standards. Examples of applications to chronic diseases include the use of PCORNet[32] to create a common data model for patients affected by metabolic diseases, or of eMERGE to secondary data analysis for personalized medicine and phenotype definition in Type 2 diabetes.[33][34]

One of the most widely used open source tools to collect multidimensional data by aggregating different sources is the Informatics for Integrating Biology and the Bedside (i2b2) framework (https://www.i2b2.org). i2b2 is one of the seven centers funded by the NIH Roadmap for Biomedical Computing (http://www.ncbcs.org). The mission of i2b2 is to provide clinical investigators with a service-based software infrastructure able to integrate clinical records and research data, and easily query them. To facilitate the query process, data are mapped to concepts organized in an ontology-like structure. i2b2 ontologies aim at organizing concepts related to each data stream in a hierarchical structure. For example, drug prescriptions can be represented through their ATC drug codes in the drug ontology[35], or a subset of laboratory tests from anatomical pathology can be linked to the SNOMED ontology.[36] Furthermore, i2b2 is linked to ontologies available from BioPortal (http://i2b2.bioontology.org/) in order to integrate the most common medical ontologies into the system.

Since it was developed, the i2b2 framework has involved other parallel projects. The interoperability project “Substitutable Medical Applications and Reusable Technologies” (SMART) was devoted to developing a platform that allows medical applications to be written once and then run across different healthcare IT systems.[37] SMART has been updated to take advantage of the clinical data models and the application programming interface described in a new, openly licensed Health Level Seven (HL7) draft standard called Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR). The new platform is called SMART on FHIR[38], and it has been recently exploited to build an interface that serves patient data from i2b2 repositories.[39] I2b2/SMART can thus effectively implement the sidecar approach, which allows clinicians to continue using existing clinical systems (EHR) as-is while resorting to a secondary database (the i2b2 instance) for decision making.

When big data are specifically exploited for clinical decision support, visual analytics enables hypothesis generation and facilitates real-time clinical decisions.[40][41][42] Visual analytics can be a powerful tool if used in combination with longitudinal models to analyze long time series[43][44] and to enhance pattern visualization to focus attention in monitoring clinical actions[45][46], or to detect and show patients' behaviors to identify health-risk scenarios.[47]

There are also several examples of CDSSs where visual analytics methods combine evidence-based and data-driven approaches to improve clinical performances, for example by retrieving drug interactions[48][45], by combining analytics and electronic guidelines[49] or by gathering EHR data and entering them into models able to perform risk stratification.[50] There are attempts to use visual analytics into field of epidemiology to understand the interaction among time dependent variables.[51]

Building effective clinical decision systems: Concepts and methods to “close” the loop of the learning health cycle

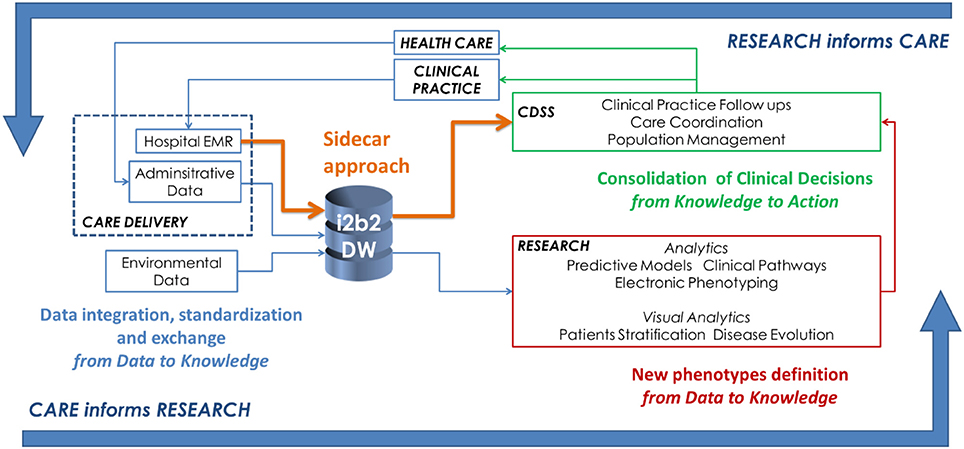

Leveraging on the existing components described in the previous section, an effective infrastructure to implement LHSC is shown in Figure 1. There are three main activity classes:

1. The activities associated to gathering data from healthcare delivery actions are represented in blue. This step encompasses activities related to data integration, standardization, and exchange, to support the translation of the information gathered during clinical practice into relevant knowledge that supports new scientific evidence.

2. Research efforts to develop analytical methods for knowledge discovery from heterogeneous data are represented in red. In particular, within the big data context, we suggest that one of the main focus is the definition of new phenotypes which are computationally manageable and able to describe disease behaviors.

3. Informatics activities related to CDSS's implementation to transfer research findings into medical and organizational actions are represented in green. In this schema, we show how is it possible to use the sidecar approach (in orange) as suggested by the SMART on FHIR example.

|

Data should be gathered from heterogeneous sources and contexts such as hospital EHRs and local health care agency information systems. The data warehouse structures have to be implemented, taking into account also clinical practice, since it can also be exploited by the CDSS. Focusing on chronic disease management, important steps include:

- the definition of a data model (e.g., an ontology) able to represent the most important features of chronic populations (i.e., diseases profiles, environmental, and behavioral factors);

- the secondary use of data originally collected for administrative purposes (e.g., patients' drug purchases);

- the retrospective collection of multivariate longitudinal data;

- the inclusion of modules for managing patients' generated data, provided by telecare services; and

- the capability of providing decision support to both patients and caregivers.

Researchers should focus on analytical methods able to reconstruct disease evolution from longitudinal and sparse data. This highlightd the importance of defining new phenotypes which are computationally manageable and able to describe disease behaviors. The main directions are focused on the use of heterogeneous data structured data, text, images, and signals in electronic phenotyping and on the exploitation of these findings into a CDSS.

The consolidation of clinical decision encompasses two main topics. The first one is related to the need of informatics applications able to deliver comprehensive knowledge about disease subtypes, diagnoses, and therapies. The second topic is about the development of tools that support custom workflows, novel analytics, data visualization, and data aggregation. It regards all the activities that allowed closing the LHSC while exporting the knowledge derived from the research activities into real clinical actions. To this end, it would be important to implement visual analytics strategies that enable fast patient stratification. Mining of algorithms and their results has to be integrated into a CDDS to make the concept of “research informs care” effective.

The final delivered systems should fully exploit big data technologies, ranging from distributed storage and computation to schema-less data models, to allow novel decision-making models. CDSS users' actions to extract new insights on patients' care flows must be conveyed by a process that integrates methodological novelties into established clinical approaches. For example, the usability experience might be structured to guide temporal data exploration, where visual analytics solutions, together with medical knowledge, facilitate the detection of risk profiles.

Implementations of CDSSS: Two examples based on the learning healthcare cycle

As effective examples of the implementation of LHSC, we illustrate two CDSSs designed and implemented by the University of Pavia and the IRCCS Istituti Clinici Scientifici (ICSM) of Pavia: one to prevent diabetes complications, and one to support arrhythmogenic disease research and clinical care.

The Mosaic Project

The system has been developed within the EU “MOSAIC” project, aimed at supporting diabetes management by resorting to advanced mathematical modeling solutions. As described by Dagliati et al.[52], we have developed a system that integrates data coming from hospitals and public health repositories. The data is collected into an i2b2 data warehouse and exploited via advanced temporal analytics tools focused on diabetes complications. Such tools include risk prediction models, temporal abstractions, careflow mining, and drug exposure patterns detection. Different users have access to the model results through a “dashboard” interface that allows clinical decision support during follow-up encounters and periodic outcome assessment of the whole cohort.

The system has been validated in a pilot study on more than 700 ICSM patients, showing a reduction in visit duration (p << 0.01), an increased number of screening exams for complications (p < 0.01), and an increase in lifestyle interventions (from 69% to 77% of the visits).

Integrated molecular cardiology system

LHSC is the basis of the current implementation of an integrated system to support research and clinical care in arrhythmogenic diseases running at ICSM. Such a system is based on an EHR linked with a CDSS for genetic variant classification and on a registry semiautomatically synchronized with the EHR.

Mantra is the EHR that collects the molecular and clinical data about patients of the molecular cardiology unit at ICS Maugeri.[53] It collects information on more than 20,000 individuals, mainly affected by Long QT syndrome (>9,000 patients), Brugada syndrome (>6,000 patients), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (>900 patients), and catecholaminergic polymorphic centricular tachycardia (>900 patients).

Mantra exports data to the Transatlantic Registry of Inherited Arrhythmogenic Diseases (TRIAD). TRIAD is a prospective registry of inherited arrhythmogenic diseases active at ICSM since 2000. It serves as a platform to improve the knowledge on genetic diseases causing life-threatening arrhythmia in the structurally normal heart. Currently, the registry counts 9,700 patients and 29,000 visits. The main considered diseases are Long QT syndrome (5,000 patients), Brugada syndrome (3,000 patients), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (550 patients), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (350 patients). The data stored in TRIAD are collected during outpatient visits and phone follow-ups, and they include the results of instrumental exams and cardiac events related to the diseases. An i2b2 instance of TRIAD has been implemented, too, in order to allow fast querying and retrieval of the collected data.[53]

Mantra has been recently linked with the variant interpreter software Cardiovai (http://cardiovai.engenome.com), which implements a systematic approach to the classification of variants according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines. Most of the ACMG/AMP criteria are implemented relying on data integration of different omics resources such as ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), MedGen (http://www.medgen.co.uk), ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and PaPI (http://papi.unipv.it). However, other criteria were tailored to cardiovascular diseases. The software was tested on benchmark datasets reporting high concordance both for pathogenic and benign variants.[54]

Conclusions

In medical informatics, big data technologies are providing new powerful instruments to gather and jointly analyze large volumes of heterogeneous data collected for different purposes, including clinical care, administration, and research. This makes possible the effective implementation of the “learning healthcare system cycle,” where healthcare practice and research play a synergistic role. In particular, clinical decision support can be strongly enabled by providing fast access to the same set of heterogeneous data available also for research purposes. The proper design of dashboard-based tools may enable precision medicine decision-making and case-based reasoning.

In this paper, we have shown two successful examples of the LSHC. The MOSAIC project has shown that decision support tools can be effectively implemented by integrating multiple sources of data and by resorting to big-data-oriented visual and predictive analytics. The temporal dimension of data has been used to deepen the insights on diabetes monitoring, allowing a better understanding of clinical phenomena, recognizing novel phenotypes, and triggering suitable clinical actions. The second example concerns a molecular cardiology integrated system, where the combination of different software tools is exploited to translate as fast as possible the results of molecular research into clinical decisions.

CDSSs that embed big data represent a novel opportunity to support clinical diagnostics, therapeutic interventions, and research. When information is properly organized and displayed, it may highlight clinical patterns not previously considered. This generates new reasoning cycles where explanatory assumptions can be formed and evaluated. Therefore, the future design of such novel CDSSs needs to support entailments among events by properly modeling and updating the different aspects of clinical care. Formal models of clinical guidelines and care pathways can be very effective tools to compare the analytics results with expected behaviors. This may permit clinicians to effectively revise routinely collected data, to get new insights about patients' outcomes, and to explain clinical patterns. All these actions are the essence of a learning health care system.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the ICS Maugeri and by the Mosaic project, funded by the European Union. We gratefully acknowledge Federico Dagostin for revising an early draft of the paper.

Ethics statement

Two effective implementations are reported, concerning decision support in diabetes (the study protocol was approved by the ICSM Ethics Committee - ID# 2100 CE) and in inherited arrhythmogenic diseases (the electronic registry was approved by the ICSM Ethics Committee - ID# 911 CEC). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Author contributions

AD wrote the first draft of the paper and contributed to its conception. RB had the original idea and revised the paper. LS revised the paper and contributed to its conception. VT contributed to the software projects. AMal, AMaz, CN, and SP worked on the arrhythmogenic disease project. PD and LC worked on the Mosaic project. MG developed Mantra. IL developed eVai.

Conflict of interest statement

Some of the software solutions mentioned in the paper are proprietary software (eVai and Mantra). IL is shareholder of Engenome s.r.l., RB is shareholder of Biomeris s.r.l. and Engenome s.r.l.

The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- ↑ Harper, E. (2014). "Can big data transform electronic health records into learning health systems?". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 201: 470–5. PMID 24943583.

- ↑ Murdoch, T.B.; Detsky, A.S. (2013). "The inevitable application of big data to health care". JAMA 309 (13): 1351–2. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.393. PMID 23549579.

- ↑ Etheredge, L.M. (2014). "Rapid learning: A breakthrough agenda". Health Affairs 33 (7): 1155-62. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0043. PMID 25006141.

- ↑ Halamka, J.D. (2014). "Early experiences with big data at an academic medical center". Health Affairs 33 (7): 1132-8. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0031. PMID 25006138.

- ↑ Krumholz, H.M. (2014). "Big data and new knowledge in medicine: the thinking, training, and tools needed for a learning health system". Health Affairs 33 (7): 1163-70. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0053. PMC PMC5459394. PMID 25006142. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5459394.

- ↑ Zillner, S.; Lasierra, N.; Faix, W.; Neururer, S. (2014). "User needs and requirements analysis for big data healthcare applications". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 205: 657–61. PMID 25160268.

- ↑ Kaltoft, M.K.; Nielsen, J.B.; Salkeld, G.; Dowie, J. (2014). "Enhancing informatics competency under uncertainty at the point of decision: A knowing about knowing vision". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 205: 975–9. PMID 25160333.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kohn, M.S.; Sun, J.; Knoop, S. et al. (2014). "IBM's Health Analytics and Clinical Decision Support". Yearbook of Medical Informatics 9: 154–62. doi:10.15265/IY-2014-0002. PMC PMC4287097. PMID 25123736. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4287097.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lupse, O.S.; Crisan-Vida, M.; Stoicu-Tivadar, L.; Bernard, E. (2014). "Supporting diagnosis and treatment in medical care based on Big Data processing". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 197: 65–9. PMID 24743079.

- ↑ Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.L.; Han, L.N.; Li, T.L. (2016). "Application and Exploration of Big Data Mining in Clinical Medicine". Chinese Medical Journal 129 (6): 731-8. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.178019. PMC PMC4804421. PMID 26960378. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4804421.

- ↑ Moghimi, F.H.; Cheung, M.; Wickramasinghe, N. (2013). "Applying predictive analytics to develop an intelligent risk detection application for healthcare contexts". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 192: 926. PMID 23920700.

- ↑ Earley, S. (2014). "Big Data and Predictive Analytics: What's New?". IT Professional 16 (1): 13–15. doi:10.1109/MITP.2014.3.

- ↑ Chen, Y.; Yang, H. (2014). "Heterogeneous postsurgical data analytics for predictive modeling of mortality risks in intensive care units". Proceedings from the 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2014: 4310–4314. doi:10.1109/EMBC.2014.6944578.

- ↑ Wang, L.Y.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. et al. (2015). "Time-dependent variation of pathways and networks in a 24-hour window after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury". BMC Systems Biology 9: 11. doi:10.1186/s12918-015-0152-4. PMC PMC4355473. PMID 25884595. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4355473.

- ↑ Grossman, C.; Goolsby, W.A.; Olsen, L; McGinnis, J.M. (2011). Engineering a Learning Healthcare System - A Look at the Future: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press. ISBN 09780309120647. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12213/engineering-a-learning-healthcare-system-a-look-at-the-future.

- ↑ Skiba, D.J. (2011). "Informatics and the learning healthcare system". Nursing Education Perspectives 32 (5): 334-6. PMID 22029247.

- ↑ Deeny, S.R.; Steventon, A. (2015). "Making sense of the shadows: Priorities for creating a learning healthcare system based on routinely collected data". BMJ Quality and Safety 24 (8): 505–15. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004278. PMC PMC4515981. PMID 26065466. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4515981.

- ↑ Budrionis, A.; Bellika, J.G. (2016). "The Learning Healthcare System: Where are we now? A systematic review". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 64: 87-92. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2016.09.018. PMID 27693565.

- ↑ Harle, C.A.; Lipori, G.; Hurley, R.W. (2016). "Collecting, Integrating, and Disseminating Patient-Reported Outcomes for Research in a Learning Healthcare System". EGEMS 4 (1): 1240. doi:10.13063/2327-9214.1240. PMC PMC4975567. PMID 27563683. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975567.

- ↑ Lee, C.H.; Yoon, H.J. (2017). "Medical big data: Promise and challenges". Kidney Research and Clinical Practice 36 (1): 3–11. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.2017.36.1.3. PMC PMC5331970. PMID 28392994. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5331970.

- ↑ Tenenbaum, J.D.; Avillach, P.; Benham-Hutchins, M. et al. (2016). "An informatics research agenda to support precision medicine: Seven key areas". JAMIA 23 (4): 791–5. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocv213. PMC PMC4926738. PMID 27107452. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4926738.

- ↑ Hripcsak, G.; Albers, D.J. (2013). "Next-generation phenotyping of electronic health records". JAMIA 20 (1): 117–21. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001145. PMC PMC3555337. PMID 22955496. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3555337.

- ↑ Newton, K.M.; Peissig, P.L.; Kho, A.N. et al. (2013). "Validation of electronic medical record-based phenotyping algorithms: Results and lessons learned from the eMERGE network". JAMIA 20 (e1): e147–54. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000896. PMC PMC3715338. PMID 23531748. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3715338.

- ↑ Richesson, R.L.; Hammond, W.E.; Nahm, M. et al. (2013). "Electronic health records based phenotyping in next-generation clinical trials: A perspective from the NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory". JAMIA 20 (e2): e226–31. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001926. PMC PMC3861929. PMID 23956018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3861929.

- ↑ Sim, I.; Gorman, P.; Greenes, R.A. et al. (2001). "Clinical decision support systems for the practice of evidence-based medicine". JAMIA 8 (6): 527–34. PMC PMC130063. PMID 11687560. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC130063.

- ↑ Belard, A.; Buchman, T.; Forsberg, J. et al. (2017). "Precision diagnosis: A view of the clinical decision support systems (CDSS) landscape through the lens of critical care". Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 31 (2): 261–71. doi:10.1007/s10877-016-9849-1. PMID 26902081.

- ↑ Bourne, P.E.; Bonazzi, V.; Dunn, M. et al. (2015). "The NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative". JAMIA 22 (6): 1114. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocv136. PMC PMC5009910. PMID 26555016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5009910.

- ↑ McCarty, C.A.; Chisholm, R.L.; Chute, C.G. et al. (2011). "The NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) initiative". JAMIA 4: 13. doi:10.1186/1755-8794-4-13. PMC PMC3038887. PMID 21269473. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3038887.

- ↑ Fleurence, R.L.; Curtis, L.H.; Califf, R.M. et al. (2014). "Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network". JAMIA 21 (4): 578-82. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002747. PMC PMC4078292. PMID 24821743. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4078292.

- ↑ Cimino, J.J.; Friedmann, B.E.; Jackson, K.M. et al. (2007). "Redesign of the Columbia University Infobutton Manager". AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2007: 135–9. PMC PMC2655841. PMID 18693813. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2655841.

- ↑ Cimino, J.J.; Overby, C.L.; Devine, E.B. et al. (2013). "Practical choices for infobutton customization: Experience from four sites". AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2013: 236-45. PMC PMC3900175. PMID 24551334. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900175.

- ↑ McGlynn, E.A.; Lieu, T.A.; Durham M.L. et al. (2014). "Developing a data infrastructure for a learning health system: The PORTAL network". JAMIA 21 (4): 596-601. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002746. PMC PMC4078291. PMID 24821738. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4078291.

- ↑ Yazdanpanah, M.; Chen, C.; Graham, J. (2013). "Secondary analysis of publicly available data reveals superoxide and oxygen radical pathways are enriched for associations between type 2 diabetes and low-frequency variants". Annals of Human Genetics 77 (6): 472–81. doi:10.1111/ahg.12035. PMC PMC4254771. PMID 23941231. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4254771.

- ↑ Hall, M.A.; Dudek, S.M.; Goodloe, R. (2014). "Environment-wide association study (EWAS) for type 2 diabetes in the Marshfield Personalized Medicine Research Project Biobank". Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 2014: 200–11. PMC PMC4037237. PMID 24297547. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4037237.

- ↑ Dagliati, A.; Sacchi, L.; Bucalo, M. et al. (2014). "A data gathering framework to collect Type 2 diabetes patients data". Proceedings from the IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI) 2014: 244–247. doi:10.1109/BHI.2014.6864349.

- ↑ Segagni, D.; Tibollo, V.; Dagliati, A. et al. (2012). "An ICT infrastructure to integrate clinical and molecular data in oncology research". BMC Bioinformatics 13 (Suppl. 4): S5. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-13-S4-S5. PMC PMC3303735. PMID 22536972. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3303735.

- ↑ Mandl, K.D.; Mandel, J.C.; Murphy, S.N. et al. (2012). "The SMART Platform: early experience enabling substitutable applications for electronic health records". JAMIA 19 (4): 597-603. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000622. PMC PMC3384120. PMID 22427539. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3384120.

- ↑ Mandel, J.C.; Kreda, D.A.; Mandl, K.D. et al. (2016). "SMART on FHIR: A standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records". JAMIA 23 (5): 899–908. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocv189. PMC PMC4997036. PMID 26911829. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4997036.

- ↑ Wagholikar, K.B.; Mandel, J.C.; Klann, J,G. et al. (2017). "SMART-on-FHIR implemented over i2b2". JAMIA 24 (2): 398–402. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocw079. PMC PMC5391721. PMID 27274012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5391721.

- ↑ Ola, O.; Sedig, K. (2014). "The challenge of big data in public health: An opportunity for visual analytics". Online Journal of Public Health Informatics 5 (3): 223. doi:10.5210/ojphi.v5i3.4933. PMC PMC3959916. PMID 24678376. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3959916.

- ↑ Vaitsis, C.; Nilsson, G.; Zary, N. (2014). "Big data in medical informatics: Improving education through visual analytics". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 205: 1163–7. PMID 25160372.

- ↑ Simpao, A.F.; Ahumada, L.M.; Rehman, M.A. (2015). "Big data and visual analytics in anaesthesia and health care". British Journal of Anaesthesia 115 (3): 350-6. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu552. PMID 25627395.

- ↑ Mane, K.K.; Bizon, C.; Schmitt, C. et al. (2012). "VisualDecisionLinc: A visual analytics approach for comparative effectiveness-based clinical decision support in psychiatry". Journal of Biomedical Informatics 45 (1): 101-6. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2011.09.003. PMID 21963813.

- ↑ Gálvez, J.A.; Ahumada, L.; Simpao, A.F. et al. (2014). "Visual analytical tool for evaluation of 10-year perioperative transfusion practice at a children's hospital". JAMIA 21 (3): 529-34. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002241. PMC PMC3994870. PMID 24363319. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3994870.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Simpao, A.F.; Ahumada, L.M.; Desai, B.R. et al. (2015). "Optimization of drug-drug interaction alert rules in a pediatric hospital's electronic health record system using a visual analytics dashboard". JAMIA 22 (2): 361-9. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002538. PMID 25318641.

- ↑ Cánovas-Segura, B.; Campos, M.; Morales, A. et al. (2016). "Development of a clinical decision support system for antibiotic management in a hospital environment". Progress in Artificial Intelligence 5 (3): 181–197. doi:10.1007/s13748-016-0089-x.

- ↑ Juarez, J.M.; Ochotorena, J.M; Campos, M; Combi, C. (2015). "Spatiotemporal data visualisation for homecare monitoring of elderly people". Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 65 (2): 97-111. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2015.05.008. PMID 26129627.

- ↑ Resetar, E.; Reichley, R.M.; Noirot, L.A. et al. (2005). "Customizing a commercial rule base for detecting drug-drug interactions". AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2005: 1094. PMC PMC1560631. PMID 16779381. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1560631.

- ↑ Slonim, N.; Carmeli, B.; Goldsteen, A. et al. (2012). "Knowledge-analytics synergy in Clinical Decision Support". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 180: 703–7. PMID 22874282.

- ↑ Gotz, D.; Stavropoulos, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, F. (2012). "ICDA: A platform for Intelligent Care Delivery Analytics". AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2012: 264–73. PMC PMC3540495. PMID 23304296. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3540495.

- ↑ Chui, K.K.; Wenger, J.B.; Cohen, S.A.; Naumova, E.N. (2011). "Visual analytics for epidemiologists: Understanding the interactions between age, time, and disease with multi-panel graphs". PLoS One 6 (2): e14683. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014683. PMC PMC3039641. PMID 21347221. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3039641.

- ↑ Dagliati, A.; Sacchi, L.; Tibollo, V. et al. (2018). "A dashboard-based system for supporting diabetes care". JAMIA 25 (5): 538-547. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx159. PMID 29409033.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Segagni, D.; Tibollo, V.; Dagliati, A. et al. (2012). "CARDIO-i2b2: integrating arrhythmogenic disease data in i2b2". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 180: 1126–8. PMID 22874375.

- ↑ Limongelli, I.; Nicora, G.; Gambelli, P. et al. (2017). "An automated guidelines-based approach for variants pathogenicity assessment in the diagnosis of genetic cardiovascular diseases". Precedenti XX Congresso Nazionale SIGU: 112.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to grammar, spelling, and presentation, including the addition of PMCID and DOI when they were missing from the original reference.