Journal:Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: Is pathology ready?

| Full article title |

Preferred names, preferred pronouns, and gender identity in the electronic medical record and laboratory information system: Is pathology ready? |

|---|---|

| Journal | Journal of Pathology Informatics |

| Author(s) |

Imborek, Katherine L.; Nisly Nicole L.; Hesseltine, Michael J.; Grienke, Jana; Zikmund, Todd A.; Dreyer, Nicholas R.; Blau, John L.; Hightower, Maia; Humble, Robert M.; Krasowski, Matthew D. |

| Author affiliation(s) | University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics |

| Primary contact | Email: Available w/ login |

| Year published | 2017 |

| Volume and issue | 8 |

| Page(s) | 42 |

| DOI | 10.4103/jpi.jpi_52_17 |

| ISSN | 2153-3539 |

| Distribution license | Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported |

| Website | http://www.jpathinformatics.org |

| Download | http://www.jpathinformatics.org/temp/JPatholInform8142-6286959_172749.pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

Background: Electronic medical records (EMRs) and laboratory information systems (LISs) commonly utilize patient identifiers such as legal name, sex, medical record number, and date of birth. There have been recommendations from some EMR working groups (e.g., the World Professional Association for Transgender Health) to include preferred name, pronoun preference, assigned sex at birth, and gender identity in the EMR. These practices are currently uncommon in the United States. There has been little published on the potential impact of these changes on pathology and LISs.

Methods: We review the available literature and guidelines on the use of preferred name and gender identity on pathology, including data on changes in laboratory testing following gender transition treatments. We also describe pathology and clinical laboratory challenges in the implementation of preferred name at our institution.

Results: Preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity have the most immediate impact on the areas of pathology with direct patient contact such as phlebotomy and transfusion medicine, both in terms of interaction with patients and policies for patient identification. Gender identity affects the regulation and policies within transfusion medicine, including blood donor risk assessment and eligibility. There are limited studies on the impact of gender transition treatments on laboratory tests, but multiple studies have demonstrated complex changes in chemistry and hematology tests. A broader challenge is that, even as EMRs add functionality, pathology computer systems (e.g., LIS, middleware, reference laboratory, and outreach interfaces) may not have functionality to store or display preferred name and gender identity.

Conclusions: Implementation of preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity presents multiple challenges and opportunities for pathology.

Keywords: clinical laboratory information system, electronic health records, gender dysphoria, medical informatics, transgender

Introduction

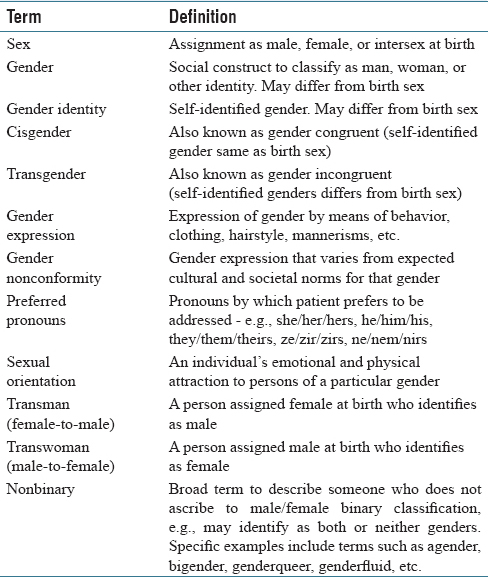

Electronic medical records (EMRs) and patient identification labels generally use patient legal name, date of birth, and a medical record number as key identifiers for patients.[1][2] Laboratory information systems (LISs) and middleware software also use these identifiers along with additional items such as accession and surgical pathology case numbers.[3] Although the legal name is most commonly used in EMRs, many patients have a “preferred name” that differs from their legal first name [Table 1]. The preferred name may be a nickname (e.g., “Bill” for “William”), use of a middle name, or some other name altogether. For transgender patients, the preferred name may match their affirmed gender and also be recognizable as of a different gender than the name assigned at birth.[4] The use of preferred name can have a positive customer service benefit in allowing for healthcare staff to address the patient in a manner chosen by the patient, whether or not they elect to provide a preferred name. The use of preferred name for transgender patients has been identified as important in providing inclusion toward a class of patients that have historically been disenfranchised from the healthcare system.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

|

Transgender is a term for individuals whose gender identity or expression does not align with their assigned birth sex and/or whose gender identity is outside of a binary (i.e., male/female) gender classification.[10][11] Cisgender refers to those whose gender identity or expression aligns with their assigned birth sex. Preferred pronoun refers to the pronouns that reflect a person's gender identity and expression (e.g., he/him/his for trans- or cis-gender males; she/her/hers for trans- or cis-gender females).[4][11] For people who do not ascribe to the male/female binary classification (“nonbinary”), nonbinary pronouns (ze/zir/zirs, hir/hirs, ne/nir/nirs, they/them/their) may be preferred. Transgender people can have their legal identity documents (e.g., passports, driver's license) changed to a different gender although laws vary in different countries and localities. Within the United States, there is significant variation in state laws in officially changing gender identity.[12][13] Even for those states that allow this, the requirements can vary (e.g., whether surgical reassignment is necessary or whether hormonal therapy alone may suffice). A detailed description of the process for one state (Iowa) is available online.[14] It is also important to keep in mind that gender identity and sexual orientation (emotional and physical attraction to persons of a particular gender) are distinct concepts.[10][11] For example, a transwoman may be attracted to men, women, or both genders. As will be discussed below, terminology related to gender identity and sexual orientation can be particularly confusing in the blood donor criteria setting.

Although preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity might have a minor impact for some patients, use of these has been identified as an important step in providing inclusive care for transgender patients.[4][5][9][11][15][16][17][18][19][20] Final rules issued by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in October 2015 require EMR software certified for meaningful use to include fields for gender identity and sexual orientation.[15] An EMR working group from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health recommended that the basic demographic variables of an EMR include preferred name, gender identity, and pronoun preference as identified by patients.[21]

Although the inclusion of preferred name into the EMR and LIS clinical workflow might seem to be relatively straightforward, there are a number of potential complications. For example, there may be regulations for certain hospital practices that require the use of full legal name and where a preferred name is not an acceptable identifier. In addition, while an EMR may have functionality for a preferred name field, other informatics systems that transmit data into the EMR (e.g., pathology, pharmacy, and radiology) may not have this functionality. The use of preferred name especially impacts staff that has direct patient contact, including phlebotomists and schedulers within pathology. An excellent resource by the National LGBT Health Education Center details best practices for front line healthcare staff for the transgender and gender nonconforming patient population.[13]

In this report, we discuss pathology-related informatics challenges with preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity. We encountered some of these issues during the implementation of preferred name at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC), a state academic medical center. We present a detailed description of the overall preferred name project elsewhere but here focus on the pathology-specific issues. As more institutions incorporate preferred name, pronoun preference, and gender identity into the EMR, clinical laboratories and pathology practices will encounter these issues more often.

Preferred name implementation: Lessons learned at University of Iowa

Institutional details

The institution of this study, UIHC, is a 734-bed state academic medical center that includes pediatric and adult inpatient units, multiple intensive care units, emergency room with level one trauma capability, and outpatient services. UIHC has a multidisciplinary lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ) clinic staffed by providers well versed in the specific needs of LGBTQ patients. UIHC has been recognized as a Healthcare Equality Index national leader by the Human Rights Campaign since 2013 because of its institutional commitment to LGBTQ equality and inclusion.[22] The EMR throughout the UIHC healthcare system has been Epic (EpicCare Inpatient and EpicCare Ambulatory, Madison, WI, USA) since 2009. The LIS for all clinical laboratories is Epic Beaker, with Beaker Clinical Pathology (CP) implemented in 2014[23] and Beaker Anatomic Pathology in 2015. Middleware software (Instrument Manager, Data Innovations, Burlington, VT, USA) is used throughout the clinical laboratories for interfacing of laboratory instruments to the LIS.[24] The LIS for the UIHC DeGowin Blood Center is software from Haemonetics (Braintree, MA, USA).

In August 2016, UIHC implemented preferred name throughout all clinical areas. There was interest in also having preferred pronouns available in the EMR; however, this discussion was deferred due to lack of robust functionality in the EMR to support this function. Pathology presented some challenges in the preferred name project. The most significant challenge was in aligning necessary changes to the institutional patient identification policy to allow preferred name to satisfy patient identifier requirements for laboratory testing if permitted by local or federal regulations. This required effort by multiple hospital subcommittees. For example, patient identification and prescription medication dispensing must follow the State Board of Pharmacy regulations.

Transfusion medicine presented the most clear-cut situations where preferred name could not be used. In particular, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) regulations require that for the purposes of blood bank sample collection and blood product and cellular therapy product administration, the patient's legal first and last name, and not preferred name, must be used as one of the patient identifiers. CAP checklist item TRM.40230 (compatibility specimen labeling) requires that blood samples used for compatibility testing for transfusion medicine are labeled with the patient's first and last name. AABB Standards (30th edition) require that “identifying information on the request (for blood products) is in agreement with that of a sample label. In case of discrepancy or doubt, another sample shall be obtained (5.11.3)”. Even if preferred name was allowed by regulations, a further barrier was that the transfusion medicine LIS used at our institution (Haemonetics) did not have functionality to input or store preferred name. Our institutional policy on patient identification reinforced the legal name requirements for transfusion medicine, with the need for an exact match between the blood product label and the patient identification band and use of the patient's legal first and last name. Training of staff in the use of preferred name emphasized situations where the legal name was required, and preferred name could not substitute.

Laboratory specimen labels presented the other main challenge for the preferred name project. The major practical issue was being able to fit the preferred name on the label along with the legal name, barcode, and other information. As we described in a previous publication, barcodes presented a substantial challenge in the conversion of the UIHC LIS to Epic Beaker CP in 2014.[23] With a preexisting maximal length for the legal name of 30 characters, the preferred name could print if the legal name was less than 20 characters. If there was sufficient space on the label to print only a portion of the preferred name, it would truncate with an asterisk (*) [Figure 1]. The importance of preferred name on the Beaker LIS labels was especially important in phlebotomy interactions with transgender patients, particularly when registering patients for laboratory-only encounters or calling patients from the waiting room into phlebotomy suites.

|

In addition to the transfusion medicine LIS, the middleware system used in the UIHC CP laboratories to provide interfacing of instrument results to the LIS (Data Innovations Instrument Manager) also did not have functionality for a preferred name field. This has little impact on direct patient interactions, given that middleware barcode labels and computer terminals are only used internally within the clinical laboratories. The one practical challenge was that middleware rules are used to alert laboratory staff by paper printouts or computer flags to tasks such as needing to contact the clinical service with regard to critical values or suboptimal specimens. If staff is only looking at middleware display, they would not see preferred name even though clinical staff might use the patient preferred name in phone conversations. Thus, staff training was required to reinforce where to find preferred name.

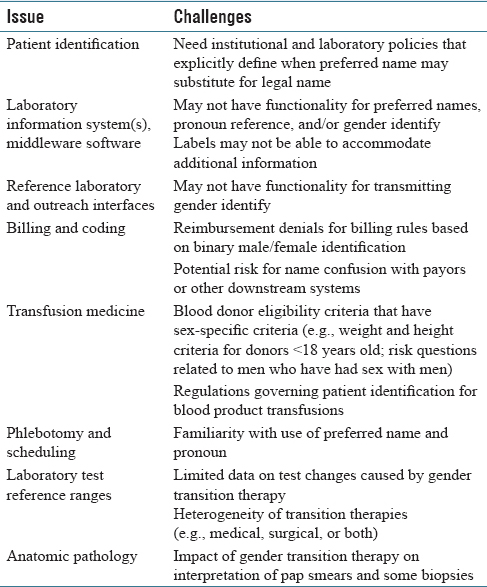

A summary of the pathology and laboratory informatics challenges is in [Table 2]. In addition to the LIS and middleware, other informatics systems such as reference laboratory and outreach interfaces may also lack functionality for preferred name and gender identity. This likely has minimal impact currently except in situations such as Pap smears, where knowledge of transgender status may aid in interpretation.

|

Broader challenges of preferred name and gender identity

Electronic medical record technical challenges

The technical task of adding preferred name in quotes under the legal name to the patient identification banner required custom build in addition to foundation EMR functionality at our institution. At project onset, the EMR (Epic 2014 version) had a field for preferred name but with minimal default functionality. Thus, much of the work to optimize the functionality required customization to allow the preferred name to display where desired and to modify the patient label to show the preferred name without impacting other label elements such as barcode. Within Epic Prelude (patient registration module), the preferred name was programmed to display in parentheses within the name field as well as in the Aliases field. Preferred name was programmed to display prominently in the patient identification field and schedule/dashboard display in the EMR. Many inquiries from end users were questions related to adding the preferred name to certain contexts within the EMRs or to optimizing existing displays. In addition to the various subcommittee meetings, it was estimated that the project took over 100 hours of dedicated time from hospital information technology (IT) personnel. This included approximately 20 hours for the training team that helped with roll out.

Significant effort was dedicated toward developing processes and scripts for front line patient care areas (including phlebotomy check-in) to query patients for preferred name preference in a standardized manner. Scripting resources included tip sheets and PowerPoint slides showing screen shots on topics such as how preferred name would be utilized in Epic Cadence (patient scheduling module) and Epic Prelude. There is also ongoing maintenance to make sure the customizations are retained with EMR upgrades. Per CMS meaningful use requirements, preferred name and gender identity vendor solutions were scheduled to become more robust in 2015 and above ONC certified EMR versions.[25] As institutions upgrade their EMRs, these IT tools will likely become widely available without the degree of customization required during our project.

Billing and coding

For the transgender patient population, challenges arise with diagnostic tests (e.g., Pap smears, prostate-specific antigen) and encounters (e.g., pregnancy) that have rules based on binary male/female identification that impacts billing and coding.[9] For instance, prostate-specific antigen testing may be denied reimbursement in a transwoman (male-to-female) even though the prostate gland is still present and testing clinically justified.[9] EMRs often structure procedures and encounters based on male/female classification. Transmission of billing data to third-party payors likely also uses only legal name to avoid confusion with multiple names.

Blood donor issues

The issue of gender identity affects eligibility for blood donation.[26][27] For example, blood donor eligibility requirements often have sex-specific height and weight criteria for double red blood cell donors and for donors younger than 18 years old.[28] In addition, blood donor questionnaires include questions on males who have had sex with other males (MSM) or females who have had sex with MSM.[27] For several decades, affirmative answers to this question led to indefinite deferral; more recently, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed the recommendation to 12 months deferral in the absence of any other reasons for deferral.[29] However, the wording of the question is still unclear with regard to transmen and transwomen since the use of gender identity instead of birth sex can change interpretation of the question.[11][27][30] For example, a transwoman who has legally changed gender identity to female may have had sex with males before transition (thus meeting definition of MSM at that time) but only be screened with the blood donor criteria relevant to females. An additional possibility is that transmen who have been previously pregnant may have circulating antibodies that have resulted from immunization to red cell antigens during pregnancy. These circulating antibodies may impact transfusion products. A more detailed analysis of the complexities and potential confusion related to blood donation in the transgender community is discussed in other publications.[26][27][31]

The most recent guidance from the FDA in 2015 is as follows: “The FDA's recommendation to blood establishments is that in the context of the donor history questionnaire, male or female gender should be self-identified and self-reported for the purpose of blood donation.”[29] The American Red Cross issued updated guidelines in March 2016 that included the following: “There is no deferral associated with being transgender, and eligibility will be based upon the criteria associated with the gender the donor has reported. Red Cross staff members are required to verbally confirm demographic information, including gender, with all presenting donors. This step helps ensure donor safety and accuracy of records. If Red Cross records have the incorrect gender, presenting donors may ask staff members to make the change upon registration. Individuals do not need to tell staff that they are transgender.”[32]

Interpretation of laboratory tests

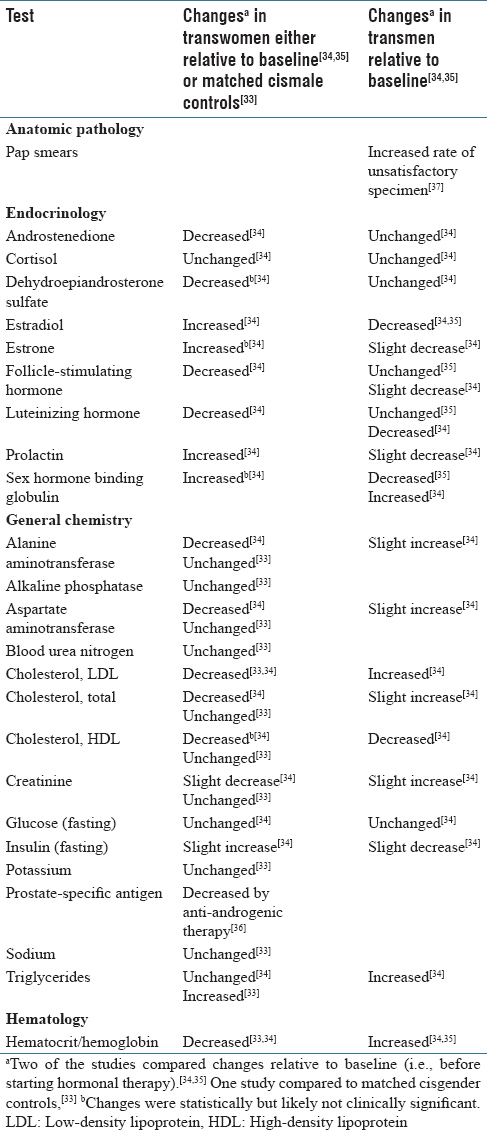

The inclusion of patient gender identity into the EMR also raises additional challenges and opportunities in that sex-based normative values are used in many laboratory reference ranges.[10][11][33] There is relatively little data on changes in laboratory testing following gender transition therapy; however, several studies have analyzed changes in laboratory testing following transitioning treatments.[33][34][35] The available studies are summarized in [Table 3]. Not surprisingly, testosterone, estradiol, and sex hormone-binding globulin change significantly following hormonal therapy in both transmen and transwomen.[34][35] In addition, significant changes in hemoglobin/hematocrit and creatinine have been observed in multiple studies.[33][34][35] Decreases in prostate-specific antigen occur in transwomen receiving antiandrogenic therapy.[36] Within AP, a high rate of inadequate specimens for Pap smears collected from transmen has been observed, a phenomenon likely related to both physical changes of testosterone therapy and patient/provider discomfort with the procedure.[37]

|

It is important to note that studies have shown that laboratory values can show a variety of changes during transition therapy including no significant change relative to baseline, resembling cisgender individuals of the new gender identity (e.g., transwomen and ciswomen), values intermediate to cisgender males and females, or values not resembling cisgender individuals of either sex.[10][33][34] Thus, providing reference ranges based on gender identity for transgender patients can potentially lead to misinterpretation. The heterogeneity of changes in laboratory values likely reflects complicated responses of individual patient physiology with the variety of hormonal regimens (e.g., hormone dose, route of administration, and combination of medications) or surgical procedures that may be used in transitioning therapies.[10][11] As an example, different magnitudes of changes in laboratory values were seen in a study of transwomen using either transdermal or oral estrogens as indicated in [Table 3].[34] These challenges represent an active area for future research, development, and education.[10]

Acknowledgments

The implementation of preferred name was a major undertaking and required the combined effort of many people from different teams. The authors would like to thank all the other individuals involved in compliance and regulatory review, policy revisions, validation, help support, training, and other key tasks in this project.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- ↑ Lichtner, V.; Wilson, S.; Galliers, J.R. (2008). "The challenging nature of patient identifiers: An ethnographic study of patient identification at a London walk-in centre". Health Informatics Journal 14 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1177/1081180X08089321. PMID 18477600.

- ↑ McCoy, A.B.; Wright, A.; Kahn, M.G. (2013). "Matching identifiers in electronic health records: implications for duplicate records and patient safety". BMJ Quality & Safety 22 (3): 219–24. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001419. PMID 23362505.

- ↑ Pantanowitz, L.; Henricks, W.H.; Beckwith, B.A. (2007). "Medical laboratory informatics". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine 27 (4): 823–43. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2007.07.011. PMID 17950900.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Deutsch, M.B.; Buchholz, D. (2015). "Electronic health records and transgender patients--Practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data". Journal of General Internal Medicine 30 (6): 843–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3148-7. PMC PMC4441683. PMID 25560316. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441683.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Donald, C.; Ehrenfeld, J.M. (2015). "The Opportunity for Medical Systems to Reduce Health Disparities Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Patients". Journal of Medical Systems 39 (11): 178. doi:10.1007/s10916-015-0355-7. PMID 26411930.

- ↑ Gridley, S.J.; Crouch, J.M.; Evans, Y. et al. (2016). "Youth and Caregiver Perspectives on Barriers to Gender-Affirming Health Care for Transgender Youth". Journal of Adolescent Health 59 (3): 254–61. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017. PMID 27235374.

- ↑ Winter, S.; Diamond, M.; Green, J. et al. (2016). "Transgender people: Health at the margins of society". Lancet 388 (10042): 390–400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8. PMID 27323925.

- ↑ Wylie, K.; Knudson, G.; Khan, S.I. et al. (2016). "Serving transgender people: Clinical care considerations and service delivery models in transgender health". Lancet 388 (10042): 401–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00682-6. PMID 27323926.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Roberts, T.K.; Fantz, C.R. (2014). "Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population". Clinical Biochemistry 47 (10–11): 983–7. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.02.009. PMID 24560655.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Goldstein, Z.; Corneil, T.A.; Greene, D.N. (2017). "When Gender Identity Doesn't Equal Sex Recorded at Birth: The Role of the Laboratory in Providing Effective Healthcare to the Transgender Community". Clinical Chemistry 63 (8): 1342–1352. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2016.258780. PMID 28679645.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Gupta, S.; Imborek, K.L.; Krasowski, M.D. (2016). "Challenges in Transgender Healthcare: The Pathology Perspective". Laboratory Medicine 47 (3): 180-8. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmw020. PMC PMC4985769. PMID 27287942. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4985769.

- ↑ "Transgender Law Center". Transgender Law Center. https://transgenderlawcenter.org/. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Affirmative Care for Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People: Best Practices for Front-line Health Care Staff" (PDF). The Fenway Institute. Fall 2016. https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Affirmative-Care-for-Transgender-and-Gender-Non-conforming-People-Best-Practices-for-Front-line-Health-Care-Staff.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Bigley, E.; Weiner, J.; Bermudez, B. et al. (1 February 2017). "The Iowa Guide to Changing Legal Identity Documents" (PDF). University of Iowa College of Law Clinical Law Programs. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/id/Iowa%20Guide%20to%20Changing%20Legal%20Identity%20Documents%20February%203%202017.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cahill, S.R.; Baker, K.; Deutsch, M.B. et al. (2016). "Inclusion of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Stage 3 Meaningful Use Guidelines: A Huge Step Forward for LGBT Health". LGBT Health 3 (2): 100–2. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0136. PMID 26698386.

- ↑ Deutsch, M.B.; Keatley, J.; Sevelius, J.; Shade, S.B. (2014). "Collection of gender identity data using electronic medical records: survey of current end-user practices". Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 25 (6): 657–63. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2014.04.001. PMID 24880490.

- ↑ MacCarthy, S.; Reisner, S.L.; Nunn, A. et al. (2015). "The Time Is Now: Attention Increases to Transgender Health in the United States but Scientific Knowledge Gaps Remain". LGBT Health 2 (4): 287–91. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2014.0073. PMC PMC4716649. PMID 26788768. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4716649.

- ↑ Callahan, E.J. (2015). "Opening the door to transgender care". Journal of General Internal Medicine 30 (6): 706–7. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3255-0. PMC PMC4441676. PMID 25743431. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4441676.

- ↑ Callahan, E.J.; Sitkin, N.; Ton, H. et al. (2015). "Introducing sexual orientation and gender identity into the electronic health record: One academic health center's experience". Academic Medicine 90 (2): 154–60. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000467. PMID 25162618.

- ↑ Unger, C.A. (2014). "Care of the transgender patient: The role of the gynecologist". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.035. PMID 23707806.

- ↑ Deutsch, M.B.; Green, J.; Keatley, J. et al. (2013). "Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: Recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group". JAMIA 20 (4): 700–3. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001472. PMC PMC3721165. PMID 23631835. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3721165.

- ↑ "Human Rights Campaign Foundation. Healthcare Equality Index 2016: Promoting Equitable and Inclusive Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Patients and Their Families" (PDF). Human Rights Campaign Foundation. 2016. ISBN 9781934765364. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/HEI_2016_FINAL.pdf. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Krasowski, M.D.; Wilford, J.D.; Howard, W. et al. (2016). "Implementation of Epic Beaker Clinical Pathology at an academic medical center". Journal of Pathology Informatics 7: 7. doi:10.4103/2153-3539.175798. PMC PMC4763507. PMID 26955505. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4763507.

- ↑ Krasowski, M.D.; Davis, S.R.; Drees, D. et al. (2014). "Autoverification in a core clinical chemistry laboratory at an academic medical center". Journal of Pathology Informatics 5 (1): 13. doi:10.4103/2153-3539.129450. PMC PMC4023033. PMID 24843824. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4023033.

- ↑ "Certified Electronic Health Record Technology (CEHRT)". Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Certification.html. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Brailsford, S.R.; Kelly, D.; Kohli, H. et al. (2015). "Who should donate blood? Policy decisions on donor deferral criteria should protect recipients and be fair to donors". Transfusion Medicine 25 (4): 234–8. doi:10.1111/tme.12225. PMID 26190553.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Custer, B.; Sheon, N.; Siedle-Khan, B. et al. (2015). "Blood donor deferral for men who have sex with men: The Blood Donation Rules Opinion Study (Blood DROPS)". Transfusion 55 (12): 2826-34. doi:10.1111/trf.13247. PMC PMC4715553. PMID 26202349. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4715553.

- ↑ "Donor History Questionnaires". AABB. http://www.aabb.org/tm/questionnaires/Pages/default.aspx. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Revised Recommendations for Reducing the Risk of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Transmission by Blood and Blood Products - Questions and Answers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/BloodBloodProducts/QuestionsaboutBlood/ucm108186.htm. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ "FDA Liaison Meeting – 11/1/12". AABB. 1 November 2012. http://www.aabb.org/advocacy/government/fdaliaison/bloodcomponents/Pages/flm110112.aspx. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ Farrugia, A.; Del Bò, C. (2015). "Some reflections on the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Blood Transfusion". Blood Transfusion 13 (4): 551–8. doi:10.2450/2015.0266-14. PMC PMC4624529. PMID 26057482. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4624529.

- ↑ "LGBTQ+ Donors". American Red Cross. http://www.redcrossblood.org/donating-blood/lgbtq-donors. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Roberts, T.K.; Kraft, C.S.; French, D. et al. (2014). "Interpreting laboratory results in transgender patients on hormone therapy". American Journal of Medicine 127 (2): 159–62. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.009. PMID 24332725.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Wierckx, K.; Van Caenegem, E.; Schreiner, T. et al. (2014). "Cross-sex hormone therapy in trans persons is safe and effective at short-time follow-up: Results from the European network for the investigation of gender incongruence". Journal of Sexual Medicine 11 (8): 1999–2011. doi:10.1111/jsm.12571. PMID 24828032.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Wierckx, K.; Van de Peer, F.; Verhaeghe, E. et al. (2014). "Short- and long-term clinical skin effects of testosterone treatment in trans men". Journal of Sexual Medicine 11 (1): 222–9. doi:10.1111/jsm.12366. PMID 24344810.

- ↑ Epstein, J.I. (1993). "PSA and PAP as immunohistochemical markers in prostate cancer". Urologic Clinics of North America 20 (4): 757-70. PMID 7505984.

- ↑ Peitzmeier, S.M.; Reisner, S.L.; Harigopal, P.; Potter, J. (2014). "Female-to-male patients have high prevalence of unsatisfactory Paps compared to non-transgender females: Implications for cervical cancer screening". Journal of General Internal Medicine 29 (5): 778-84. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2753-1. PMC PMC4000345. PMID 24424775. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4000345.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation and updates to spelling and grammar. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.