Journal:BlueTrace: A privacy-preserving protocol for community-driven contact tracing across borders

| Full article title | BlueTrace: A privacy-preserving protocol for community-driven contact tracing across borders |

|---|---|

| Author(s) | Bay, Jason; Kek, Joel; Tan, Alvin; Hau, Chai S.; Yongquan, Lai; Tan, Janice; Quy, Tang A. |

| Author affiliation(s) | Singapore's Government Technology Agency |

| Primary contact | Email: info at bluetrace dot io |

| Year published | 2020 |

| Page(s) | 1–9 |

| Distribution license | Reproduced with written permission |

| Website | https://bluetrace.io/ |

| Download | https://bluetrace.io/static/bluetrace_whitepaper-938063656596c104632def383eb33b3c.pdf (PDF) |

Abstract

TraceTogether is the first national deployment of a Bluetooth-based contact tracing system in the world. It was developed by Singapore’s Government Technology Agency and the Ministry of Health to help the country better respond to epidemics.

Following its release, more than 50 governments have expressed interest in adopting or adapting TraceTogether for their countries. Responding to this interest, we are releasing an overview of BlueTrace, the privacy-preserving protocol that underpins TraceTogether, as well as OpenTrace, a reference implementation.

OpenTrace comprises the source code for an iOS app, an Android app, a cloud-based backend, and baseline signal strength calibration data. This will be made available to the open source community at github.com/opentrace-community on 9 April 2020.

Context

Contact tracing is an important tool for reducing the spread of infectious diseases. Its goal is to reduce a disease’s effective reproductive number (R) by identifying people who have been exposed to the virus through an infected person and contacting them to provide early detection, tailored guidance, and timely treatment. By stopping virus transmission chains, contact tracing helps “flatten the curve” and reduces the peak burden of a disease on the healthcare system. Contact tracing forms an essential part of Singapore’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overview of BlueTrace

BlueTrace is a protocol for logging Bluetooth encounters between participating devices to facilitate contact tracing, while protecting the users’ personal data and privacy.

When two participating devices encounter each other, they exchange non-personally identifiable messages that contain temporary identifiers. The identifiers rotate frequently to prevent third parties from tracking users. The user’s encounter history is stored locally on their device; none of this data can be directly accessed by the health authority.

If a user is infected or is the subject of contact tracing, they will be asked to share their encounter history with the relevant health authority with the use of a PIN. (A verification code may optionally be provided, to authenticate the health authority official’s request.) Only the health authority has the ability to decrypt the shared encounter history to obtain and use personally-identifiable information and to subsequently filter for close contacts and notify potentially infected users.

BlueTrace is designed to supplement manual contact tracing by addressing its key limitation: an infected person can only report contacts they are acquainted with and remember having met. BlueTrace could also allow for contact tracing to be more scalable and less resource-intensive.

BlueTrace also allows a federated network of credentialed health authorities to each maintain distinct user bases, while allowing for contact tracing between users from different health authority jurisdictions (more later in the section "Federation and interoperability").

Data protection and privacy safeguards

We believe that even during pandemics, public health and personal privacy should not be a binary choice. BlueTrace is designed to safeguard user privacy and give users control of their data. The protocol includes the following privacy safeguards:

- Limited collection of personally-identifiable information: The only personally-identifiable information collected is a phone number, which is securely stored by the health authority.

- Local storage of encounter history: Each user’s encounter history is stored exclusively on their own device. The health authority only has access to this history when an infected person chooses to share it.

- Prevention of third-party tracking: Third parties cannot use BlueTrace communications to track users over time. A device’s temporary identifier rotates frequently, preventing malicious actors from tracking individual users over time by sniffing for BlueTrace messages.

- Revocable consent: Users have control of their personal data. When they withdraw consent, all personally-identifiable data stored at the health authority is deleted. All encounter history will thus cease to be linked to the user.

How BlueTrace works

User registration and assignment of UserID

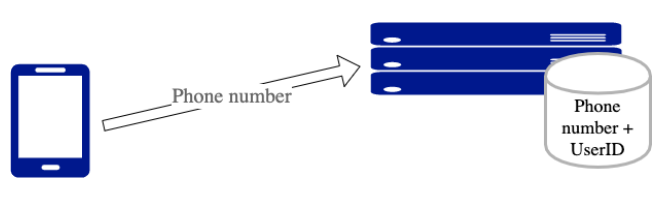

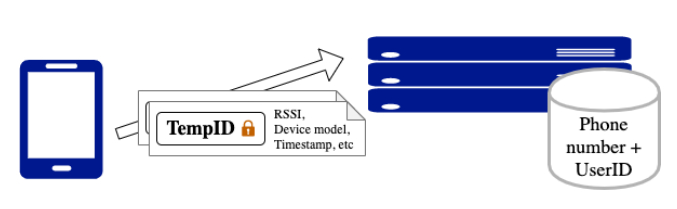

When the user of a BlueTrace-implementing app registers with their phone number, the back-end service generates a unique, randomised UserID and associates it with the user’s phone number (Figure 1).

|

Phone numbers are the only personally-identifiable information required from the user. The phone numbers are used to contact users if they are found to have had prolonged exposure to an infected person. Alternative implementations of BlueTrace that do not require a phone number are possible, however. These might rely on push notification tokens to alert individual users (see the next section "Protocol design considerations").

Generation of TempIDs

BlueTrace devices log encounters with each other by exchanging messages over Bluetooth. To protect users’ privacy, these messages cannot reveal a user's identity. Additionally, in order to prevent users from being tracked over time by third parties, these messages cannot contain static identifiers. However, when an infected user uploads these messages to the health authority, the authority must be able to obtain contact information from the messages.

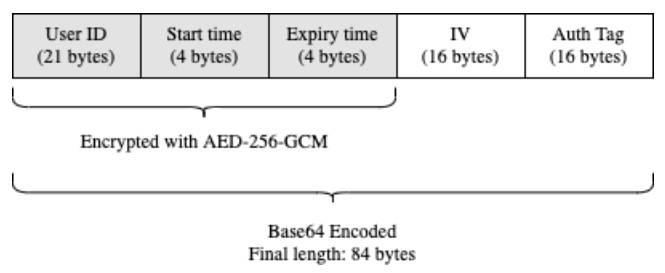

BlueTrace addresses this by having users exchange temporary IDs (TempIDs). Each TempID comprises a UserID, created time, and expiry time encrypted symmetrically with AES-256-GCM and then Base64-encoded (Figure 2). Only the health authority holds the secret key to encrypt and decrypt TempIDs. Each TempID is generated with a random initialisation vector (IV).

|

TempIDs have a short lifetime (we recommend 15 minutes). This helps to mitigate the impact of replay attacks by reducing the window of opportunity for exploitation. If malicious users impersonate other users by rebroadcasting their messages, they will only be able to do so for a short time before the message expires. This duration would likely be below the threshold duration of close contact, and hence not result in false positives (more later in the section "Encounter Message replay/relay attacks").

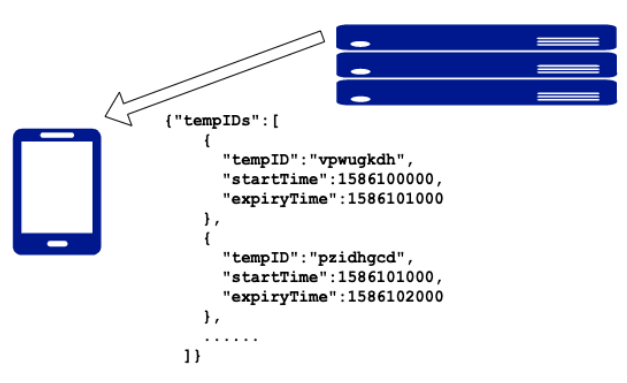

In order to ensure that devices have a supply of valid TempIDs even when the internet connection is unstable, devices pull batches of forward-dated TempIDs from the health authority’s back-end service each time (Figure 3).

|

BLE handshake flow

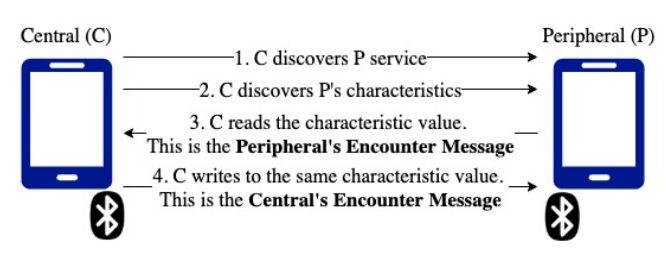

BlueTrace devices exchange messages over the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) protocol. In BLE parlance, devices can take on peripheral or central roles. Peripherals advertise services, and centrals scan for peripherals’ advertisements to connect to their services. Services are a collection of data, such as characteristics, which are specific data that can be exchanged between devices, through read and writes performed by a central role. The data exchanged by BlueTrace devices in each “handshake” is called an "encounter message."

Devices using BlueTrace act as both a central and a peripheral and may alternate between these roles. When two devices connect, the central reads the peripheral’s encounter message and then writes back its own encounter message; each connection allows for a two-way exchange of data between the central and peripheral (Figure 4). Allowing for two-way communications promotes symmetry and addresses the limitation where some devices (and possibly wearables) are only able to function as peripherals.

|

Scanning and advertising cycles

BlueTrace devices scan and advertise on configurable cycles. Scanning occurs with a duty cycle around 15 to 20%, during which devices scan for other BlueTrace devices as central. Devices may optionally introduce random jitter into the length and duty ratio of each scanning cycle to avoid lockstep behaviour.

Advertising occurs with a higher duty cycle of around 90 to 100%. We recommend a shorter duty cycle for scanning to conserve resources. We also recommend that the sum of both scanning and advertising duty cycles be greater than one to ensure that devices have the opportunity to see each other.

Blacklisting

To ensure an even distribution of Bluetooth “handshakes” with as many nearby BlueTrace devices as possible, BlueTrace devices should implement a blacklist of recently seen devices and not attempt to connect to them for the duration of the blacklist period. On both Android and iOS devices, the length of this blacklist period is between one and two scanning cycles.

Note that the blacklist can be negated by peripherals that perform device identifier randomisation regularly. On some Android devices, this can happen extremely frequently. Such devices tend to be scanned by centrals repeatedly, preventing an even distribution of encounters with nearby devices.

We are experimenting with different methods of preventing repetitive connections. We will incorporate recommended solutions within this document and make the corresponding contributions to the OpenTrace reference implementation in due course.

Encounter message

The encounter message is a UTF-8-encoded JSON file. The fields in the JSON file differ slightly depending on the direction of communication.

The peripheral’s encounter message is advertised by the peripheral as a characteristic value, so that a central can scan for and read it after discovering the peripheral and its valid vharacteristic. It is in the following format (as of Version 2):

{

// TempID of the peripheral

"id": "Fj5jfbTtDySw8JoVsCmeul0wsoIcJKRPV0HtEFUlNvNg6C3wyGj8R1utPbw+Iz8tqAdpbxR1nSvr+ILXPG==",

// Device model of the peripheral, to calibrate distance estimates

"mp": "Samsung S8",

// Organisation code indicating the country and health authority with which the peripheral is enrolled

"o": "SG_MOH",

// Version of the BlueTrace protocol that the peripheral is running

"v": 2

}

The central’s encounter message is returned to the peripheral as a characteristic value, that a central writes back to the peripheral before closing the connection. It is in the following format (as of Version 2):

{

// TempID of the central

"id": "Fj5jfbTtDySw8JoVsCmeul0wsoIcJKRPV0 HtEFUlNvNg6C3wyGj8R1utPbw+Iz8tqAdpbxR1nSvr+ILXPG==",

// Device model of the central, to calibrate distance estimates

"mc": "iPhone X",

// Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) as measured by the central of the peripheral

"rs": -60,

// Organisation code indicating the country and health authority with which the Central is enrolled

"o": "SG_MOH",

// Version of the BlueTrace protocol that the central is running

"v": 2

}

The main difference is that the message originating from central contains the RSSI field. This is necessary because although the central and peripheral communicate in both directions, only the central can record RSSI. Thus, the central records the RSSI reading of the peripheral, and then returns this information to the peripheral so that both devices have symmetric knowledge, and so that the RSSI and device model can be used to estimate distance subsequently.

In testing, we have encountered a message size limit with some devices. This message format fits well within that constraint. If there is a need to accommodate devices with smaller message size limits, it is possible to use a byte array instead of JSON, and also to base64 decode the TempID.

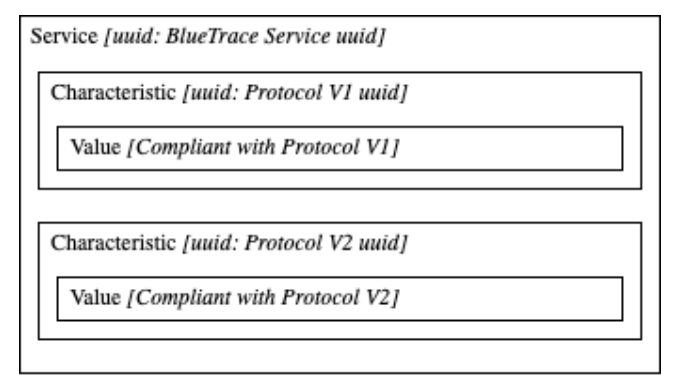

Migrations to new message formats are possible by advertising multiple characteristics within the service, each corresponding to a different protocol version. This way, devices maintain backward compatibility while allowing the protocol to evolve (Figure 5).

|

Storage of encounter history

Both central and peripheral devices store each “handshake” as an entry in its encounter history for a certain number of days (for OpenTrace, 21 days) before deletion. Devices can also be configured to log when a scan is performed, to differentiate between the absence of scanning and the absence of nearby devices.

Contact tracing flow

When patients have been confirmed to be infected, health authorities ask them if they have the app installed. If they do, they are asked to upload their encounter history to the health authority (Figure 6).

|

To protect users and the system from fraudulent uploads, an authorisation code is provided by the health authority and entered through the app in order to obtain a valid token to transmit the logs.

Data analysis flow

The health authority decrypts the TempID for each encounter in the uploaded encounter history in order to obtain the UserID and validity period. It then verifies that the encounter timestamp for each TempID falls within its validity period. The health authority then filters for close contacts based on the disease’s epidemiological parameters: time of exposure (measured by the length of a continuous cluster of encounters) and distance (measured by the received signal strength reading).

In Singapore, the contact tracing process involves an interview with the patient, where the patients are asked to recall where they have been and who they have been in contact with recently. This information is used together with the BlueTrace data to adjust the proximity and duration filtering thresholds based on the patient-reported location and context. The health authority then contacts individuals assessed to have a high likelihood of exposure to the disease, to provide medical guidance and care.

Note that this workflow can be automated and decentralised without affecting interoperability with other BlueTrace implementations. However, we do not recommend this, and we have therefore not implemented it in OpenTrace. (For further discussion, see the next section "Protocol design considerations").

Withdraw of consent

We believe users should be in control of their personal data and have the ability to delete this from the system. If a user withdraws consent to use their personal data, their UserID and phone number should be deleted from the back-end database. Since the phone number is the only source of identity, deleting it will render useless all of this user’s TempIDs that were previously sent to other devices.

Protocol design considerations

Bluetooth or GPS

Bluetooth and GPS contact tracing solutions were both considered. Table 1 illustrates the main differences.

| ||||||||||||||||||

Bluetooth was chosen because it is able to classify close contacts with a significantly lower false positive rate than GPS. Given that GPS accuracy decreases in indoor environments, entire shopping malls, or skyscrapers would be within the margin of error of a single GPS point. Furthermore, adoption could be hampered by the public wariness of location tracking and increased battery drain.

Generation of TempID by backend service vs. on device

In the reference implementation, TempIDs are cryptographically generated by the backend service. The downside is that this requires devices to connect periodically to the internet. We account for periods without connectivity by issuing a batch of TempIDs at a time.

An alternative to this approach would be for the UserID to be stored on the device, and for TempIDs to be generated locally using an asymmetric encryption key, with the backend service holding the corresponding decryption key. The asymmetric encryption key can be generated by the backend service and sent to the user device using registration. However, we found that this cryptographic scheme increased the computational requirement on devices beyond the OS-allocated limits, especially when in background execution mode.

Apart from minimising on-device compute requirements, server-side TempID generation has a secondary benefit of allowing the health authority to understand adoption and usage levels of the app by logging the issuance of daily batches of TempIDs, as well as the app's potential effectiveness in epidemic control. This could then be used to inform public health policy interventions.

Centralised vs decentralised contact tracing

BlueTrace envisages a blend of decentralised proximity data collection and logging, with a centralised contact tracing capability.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes presentation. Some grammar was corrected for clarity.