Journal:The impact of electronic health record (EHR) interoperability on immunization information system (IIS) data quality

| Full article title | The impact of electronic health record (EHR) interoperability on immunization information system (IIS) data quality |

|---|---|

| Journal | Online Journal of Public Health Informatics |

| Author(s) | Woinarowicz, Mary A.; Howell, Molly |

| Author affiliation(s) | North Dakota Department of Health, Division of Disease Control |

| Primary contact | Email: mary dot woinarowicz at nd dot gov |

| Year published | 2016 |

| Volume and issue | 8(2) |

| Page(s) | e184 |

| DOI | 10.5210/ojphi.v8i2.6380 |

| ISSN | 1947-2579 |

| Distribution license | Custom open-access |

| Website | http://ojphi.org/ojs/index.php/ojphi/article/view/6380 |

| Download | http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/ojphi/article/download/6380/5638 (PDF) |

|

|

This article should not be considered complete until this message box has been removed. This is a work in progress. |

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the impact of electronic health record (EHR) interoperability on the quality of immunization data in the North Dakota Immunization Information System (NDIIS).

Methods: NDIIS "doses administered" data was evaluated for completeness of the patient and dose-level core data elements for records that belong to interoperable and non-interoperable providers. Data was compared at three months prior to EHR interoperability enhancement to data at three, six, nine and 12 months post-enhancement following the interoperability go live date. Doses administered per month and by age group, timeliness of vaccine entry and the number of duplicate clients added to the NDIIS was also compared, in addition to immunization rates for children 19–35 months of age and adolescents 11–18 years of age.

Results: Doses administered by both interoperable and non-interoperable providers remained fairly consistent from pre-enhancement through 12 months post-enhancement. Comparing immunization rates for infants and adolescents, interoperable providers had higher rates both pre- and post-enhancement than non-interoperable providers for all vaccines and vaccine series assessed. The overall percentage of doses entered into the NDIIS within one month of administration varied slightly between interoperable and non-interoperable providers; however, there were significant changes between the percentage of doses entered within one day and within one week with the percentage entered within one day increasing and within one week decreasing with interoperability. The number of duplicate client records created by interoperable providers increased from 94 duplicates pre-enhancement to 10,552 at 12 months post-enhancement, while the duplicates from non-interoperable providers only increased from 300 to 637 over the same period. Of the 40 core data elements in the NDIIS, there was some difference in completeness between the interoperable versus non-interoperable providers. Only middle name, sex, county, phone number, mother’s maiden name, vaccine manufacturer, lot number and expiration date were significantly (>=5%) different between the two provider groups.

Conclusions: Interoperability with provider EHRs has had an impact on NDIIS data quality. Timeliness of data entry has improved and overall doses administered have remained fairly consistent, as have the immunization rates for the providers assessed. There are more technical and non-technical interventions that will need to be accomplished by NDIIS staff and vendor to help reduce the negative impact of duplicate record creation, as well as data completeness.

Keywords: Immunization information systems, electronic health records, meaningful use, HL7, data quality

Introduction

Immunization information systems (IISs) are confidential, population-based systems that record immunization administration data from participating providers, provide consolidated immunization histories at the point of care and provide aggregate data on vaccinations for use in surveillance to increase immunization rates and reduce vaccine-preventable disease.[1] In 1995, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) compiled a list of required and optional core data elements for IIS. The National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) reviewed and updated the IIS core data elements as part of their Initiative on Immunization Registries.[2] The CDC incorporated the NVAC recommendations and again updated the IIS core data elements in 2012 to correspond with the IIS functional standards and IIS Strategic Plan for 2013-2017.[3][4] The purpose of the core data elements is to help standardize the capture of data in the IIS and to facilitate the consistent exchange of data between the IIS, electronic health record (EHR) systems and other IIS.[2][3]

When the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was enacted in 2009, one of its goals was to promote the adoption and increase the “meaningful use” of EHRs.[5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), in coordination with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), have set different criteria that must be met by participating providers in order to receive an incentive payment. One of the public health reporting criteria included in all three stages of meaningful use is the electronic exchange of data between an EHR and an IIS.[6] This electronic exchange of data is referred to as interoperability. According to the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), “interoperability is the ability of different information technology systems … to … exchange data, and use the information that has been exchanged.”[7]

In 2010, the North Dakota Department of Health (NDDoH) received ARRA funding to establish real-time, bidirectional interoperability connections between the North Dakota Immunization Information System (NDIIS) and the EHRs of the state’s providers responsible for the highest volume of childhood (< 6 years) immunizations. Prior to 2010, the NDIIS was not interoperable with any providers. All providers entered immunizations directly into the NDIIS, in addition to entry into their EHR. As of August 31, 2013, the NDIIS was interoperable with 186 individual provider practices that represented more than half of all doses administered to children 18 and younger in the NDIIS.

The quality of data in an IIS is vital to its ability to determine a patient’s immunization status, calculate immunizations due, assess immunization coverage or generate reminder and recall notices.[6] Without timely and accurate data entered into the NDIIS, it cannot support its basic functionality or provide a benefit to its users or the people in its jurisdiction.[6] The NDIIS has historically maintained high data quality and provider and patient participation by having a number of data quality checks in place that help ensure a high level of data quality. However, these checks are only visible to providers manually entering data directly into the NDIIS. Providers submitting data electronically (interoperable) do not see these same validation checks or warnings if data is not complete in their EHRs.

Other IIS have evaluated the completeness of immunization records in their IIS by comparing the IIS immunization records to the records in provider offices and other facilities in order to evaluate the impact of EHR interoperability. They have found that their IIS records have had more complete immunization information since it is a consolidated record and not just record of immunizations administered at one provider practice.[8][9] North Dakota requires reporting of childhood immunizations to the IIS. According to the 2013 IIS Annual Report, the NDIIS has 96.8% of North Dakota children <6 years of age, 83.4% of adolescents 11-17 years of age and 77.9% of adults 19 years of age and older participating in the NDIIS.[10] Since the NDIIS already has excellent immunization record completeness, the NDDoH wanted to examine other areas of data quality related to the immunization record.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact of EHR interoperability on NDIIS data quality by comparing data entry, timeliness and data completeness, as well as, immunization rates for records belonging to providers submitting electronic data (i.e., interoperable) to those for providers manually entering data directly into the NDIIS (i.e., non-interoperable).

Methods

In the NDIIS, a “provider” refers to a clinic or immunization practice, not to a specific individual practitioner. A client record in the NDIIS is assigned to a provider practice if they were the last provider to enter a non-influenza vaccine in that client’s record. Data for all clients in the NDIIS with doses administered between August 1, 2011 and August 31, 2014 was extracted from the NDIIS for evaluation. Extracted data elements included client first, middle and last name; birthday; sex; birth state/country; race; ethnicity; address; phone number; mother’s first, middle and last name; vaccine type; vaccination date (dose date); lot number and vaccine-level VFC eligibility IIS core data elements.

All data extracted was separated into one of two groups based on assigned provider: records belonging to interoperable providers (IPs) and non-interoperable providers (NIPs). An IP is defined as a provider whose EHR submits data to the NDIIS electronically (i.e., without human intervention) using messaging standards set by Health Level 7 (HL7) International and as defined by the HL7 implementation guide for immunization messaging.[11][12] A NIP is defined as a provider who manually enters data directly into the NDIIS user interface in addition to documenting in their EHR or paper records. They do not submit data to the NDIIS electronically. Pre-enhancement (before interoperability) data included doses administered between August 1 and October 31, 2011, prior to the first health system EHR connection to the NDIIS. Post-enhancement (after interoperability) data included doses administered between September 1, 2013 and August 31, 2014, three through 12 months after the final provider EHRs were connected to the NDIIS.

The overall data entry analysis evaluated the total number of doses administered by IPs and NIPs per month and by age group for clients five years of age and younger, six to 10 years, 11-18 years, 19-59 years and 60 years and older. Doses for each month were summed for three months pre-enhancement and three, six, nine and 12 months post-enhancement. The data entry analysis also evaluated the number of duplicate client records added by IPs and NIPs at three months pre-enhancement and three, six, nine and 12 months post-enhancement, as well as, the timeliness of all doses entered into the NDIIS less than one day after the dose administration date, within one week (i.e., one to seven days) of administration and within one month (i.e., 30 days) for the three months pre-enhancement and three, six, nine and 12 months post-enhancement.

Completeness of IIS core data elements for client and dose records that belong to IPs and were entered into the NDIIS three months pre-enhancement and at three, six, nine and twelve months post-enhancement were calculated and compared to the completeness of records for NIPs.

Immunization rates for children 19–35 months of age for the 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 (4 diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis [DTaP], 3 polio, 1 measles, mumps and rubella [MMR], 3 hepatitis B, 3 haemophilus influenzae type B [Hib], 1 varicella and 4 pneumococcal conjugate [PCV]) vaccine series and for adolescents 11–18 years of age for one dose of tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap) and meningococcal conjugate (MCV4) vaccines, two doses of varicella and three doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines were calculated and compared for clients that belong to IPs versus NIPs for three months pre-enhancement and three, six, nine and 12 months post-enhancement. SAS 9.3, (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington) were used to analyze all NDIIS data.

Results

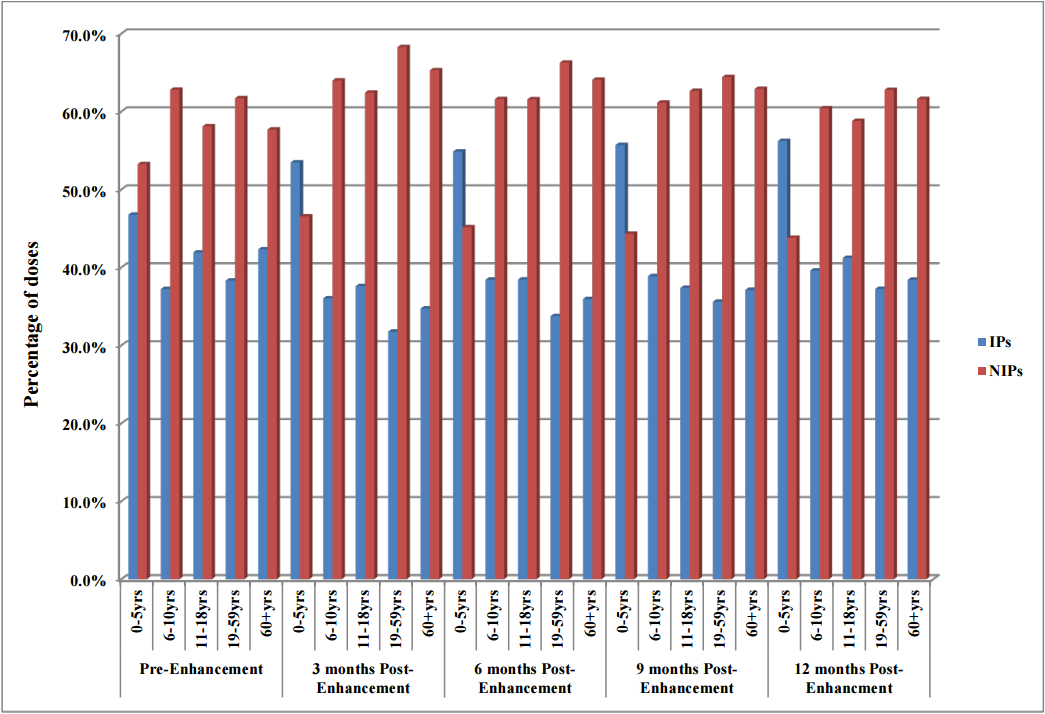

Doses administered to the 6–10 year, 11–18 year, 19–59 year and 60 years and older age groups by both IPs and NIPs remained fairly consistent from pre-enhancement to three, six, nine and 12 months post-enhancement. NIPs had a higher percentage of doses administered for all age groups with the exception of the 0–5 year age group. Pre-enhancement NIPs entered 53% of the doses in the NDIIS compared to 47% for IPs. Post-enhancement, IPs entered 53% of doses at three months, 55% at six months, 56% at nine and 12 months (Figure 1).

|

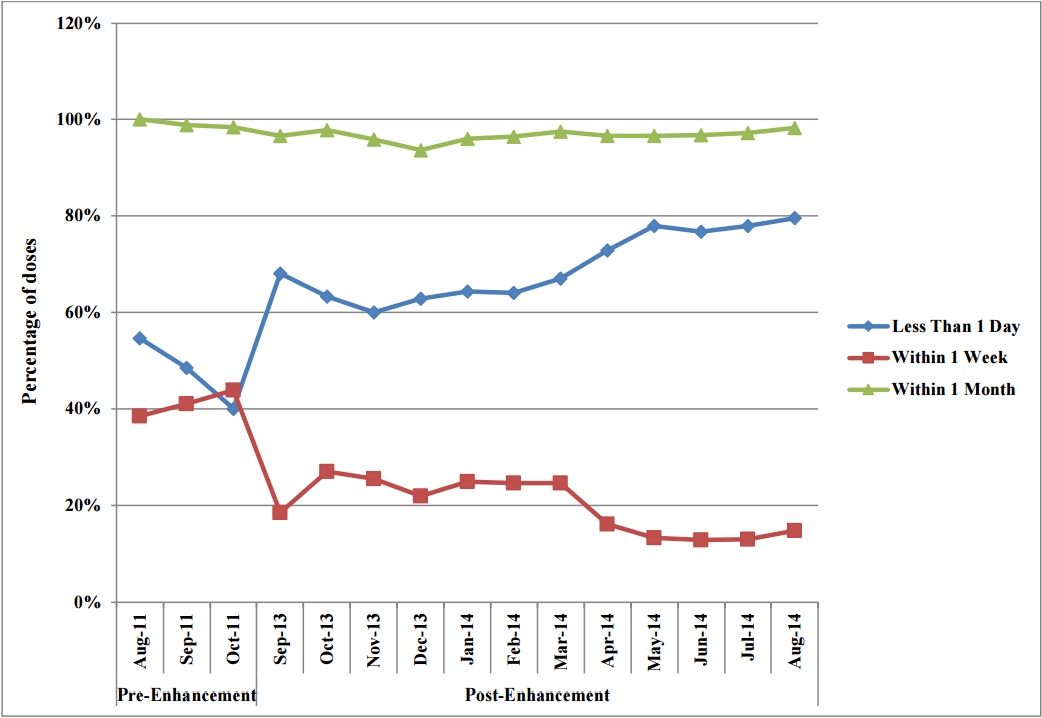

Looking at the timeliness of data entry, the overall percentage of doses entered into the NDIIS within one month of administration varied slightly (less than 2%) over the three months preenhancement and 4.6% over the 12 months post-enhancement. There were, however, some significant changes between the percentage of doses entered within one day and within one week. The percentage of doses entered within one day increased from 54.6% at the start of the pre-enhancement period to 79.5% at the end of the twelve months post-enhancement, while the doses entered within one week of administration decreased from 38.6% to 14.9% over the same time period (Figure 2).

|

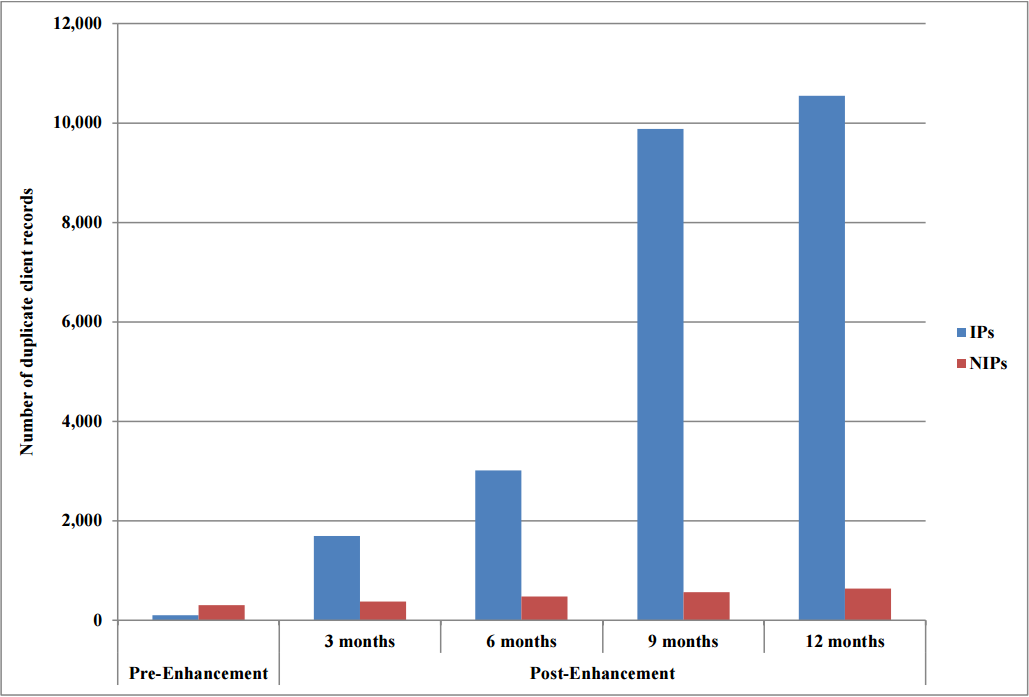

Pre-enhancement, the number of duplicate client records created in the NDIIS by NIPs was more than three times the number created by IPs (300 vs. 94). Post-enhancement, the number of duplicate client records created by NIPs increased from 377 at three months to 637 at 12 months, whereas the number of duplicate client records created by IPs increased to 1,695 at three months post enhancement and continued to increase with 9,883 duplicates created at nine months and 10,552 at 12 months (Figure 3).

|

Of the 40 core data elements in the NDIIS, completeness for only three elements (middle name, county and phone number) were significantly (>=5%) higher for NIPs compared to IPs pre-enhancement. Completeness for only two data elements (sex and mother’s maiden name) were significantly higher for IPs pre-enhancement. For all other data elements, there was no significant difference in completeness between the interoperable versus NIPs. By 12 months post-enhancement, there were five data elements (middle name, phone number, vaccine manufacturer, lot number and expiration date) significantly higher for NIPs, and completeness for mother’s maiden name was significantly higher for IPs. Additionally, completeness for sex showed almost no difference between IPs and NIPs post-enhancement, and the percentage difference in completeness for county was only 2% post-enhancement versus 5% pre-enhancement (Table 1).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Comparing immunization rates for infants and adolescents, IPs had higher rates both pre- and post-enhancement than NIPs for all vaccines and vaccine series assessed. The rate for the infant 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 series was 82% for IPs pre-enhancement and 77% for NIPs, for a difference of only 5% between the two groups. By 12 months post-enhancement, there was a difference of 12% with the IPs still having a higher percentage of their infants up-to-date with the complete series (70%) when compared to the infants of NIPs (58%) (Table 2).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ "About Immunization Information Systems". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 May 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/about.html. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 National Vaccine Advisory Committee (5 February 2007). "Immunization Information Systems, NVAC Progress Report, February 2007" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/nvpo/nvac/reports/nvaciisreport20070911.pdf. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "IIS Recommended Core Data Elements". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 December 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/core-data-elements.html. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ "Immunization Information System (IIS) Functional Standards". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 December 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/func-stds.html. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ "Electronic Health Records (EHR) Incentive Programs". Regulations and Guidance. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 29 October 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Meaningful Use and Immunization Information Systems". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 September 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/meaningful-use/index.html. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ "What is Interoperability?". HIMSS. 5 April 2013. http://www.himss.org/library/interoperability-standards/what-is-interoperability. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ Kolasa, M.S.; Cherry, J.E.; Chilkatowsky, A.P. et al. (2005). "Practice-based electronic billing systems and their impact on immunization registries". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 11 (6): 493–499. doi:10.1097/00124784-200511000-00004. PMID 16224283.

- ↑ Koepke, R.; Petit, A.B.; Ayele, R.A. et al. (2015). "Completeness and accuracy of the wisconsin immunization registry: An evaluation coinciding with the beginning of meaningful use". Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 21 (3): 273–81. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000216. PMID 25590511.

- ↑ "2013 IISAR Data Participation Rates". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 September 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/annual-report-iisar/2013-data.html#adult. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ↑ "Introduction to HL7 Standards". Health Level Seven International. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/index.cfm?ref=nav. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "IIS Health Level 7 (HL7) Implementation". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 July 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/technical-guidance/hl7.html. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added.